At the recent Los Angeles premiere for Chappaquiddick, Entertainment Studios honcho Byron Allen told Variety that “there are some very powerful people” — one of them being Chris Dodd? — “who tried to put pressure on me not to release this movie. They went out of their way to try and influence me in a negative way. I made it very clear that I’m not about the right, I’m not about the left. I’m about the truth.”

Chappaquiddick is truthful, all right. It could have been even more damning, in fact, but it conveys the necessary facts. It doesn’t slap you across the chops, but it delivers and lingers. There’s no forgetting it the next day.

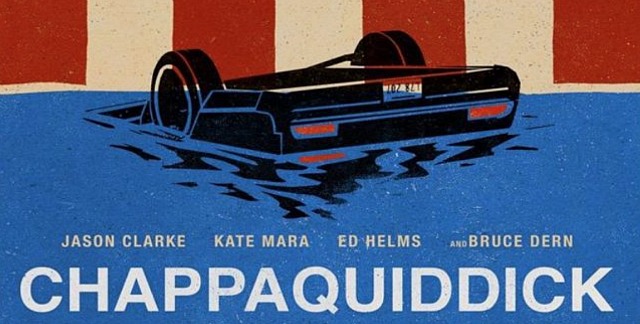

It’s about how Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (Jason Clarke) suffocated his soul late at night on 7.18.69, and thereafter showed his family and colleagues (and eventually the world) what kind of person he was. About how he recklessly and probably drunkenly drove his Oldsmobile off a small wooden bridge around 11 pm that night, plunging into the black seawater, somehow climbing out of the vehicle but failing to save his passenger, a 28 year-old campaign worker named Mary Jo Kopechne (Kate Mara). And about how Mary Jo, stuck inside the submerged, upside-down vehicle, didn’t drown but almost certainly died of gradual suffocation in an air void.

In my view (and probably in the view of those who see it this weekend), Chappaquiddick is about how irresponsible, well-connected rich guys call their friends and cover their tracks, and about how average bystanders sometimes stand by and shake their heads or shrug their shoulders and perhaps say to themselves “not mine to judge or condemn…I merely have my life to live, but the rich and powerful have their agendas to serve.”

In the late summer of ’16 I threw some praise at a 5.11.16 draft of Taylor Allen and Andrew Logan‘s Chappaquiddick script. I tore through it in no time. It’s the kind of well-finessed backroom melodrama that I love — no bullshit, subdued emotions, no tricks or games. It’s tense and well-honed, and, like I said on 8.18.16, a nightmare that had me shaking my head and muttering “Jesus H. Christ”.

Like the script, film is a damning, no-holds-barred account of the infamous July 1969 auto accident which nearly destroyed Ted Kennedy‘s political career save for some high-powered finagling and string-pulling that allowed the younger brother of JFK and RFK to wiggle out of serious trouble and more or less skate.

Just about every scene exudes the stench of an odious situation being suppressed and re-narrated by big-time fixers, many of whom are appalled at Ted’s behavior and character but who do what’s necessary regardless.

There’s no question that director John Curran, dp Maryse Alberti and editor Keith Fraase are dealing straight, compelling cards, and that the film has stuck to the ugly facts, and that it paints the late Massachusetts legislator and younger brother of JFK and RFK in a morally repugnant light, to put it mildly. It’s a frank account of how power works (or worked 49 years ago, at least) when certain people want something done and are not averse to calling in favors. EMK evaded justice by way of ingrained subservience to the Kennedy mystique, a fair amount of ethical side-stepping and several relatively decent folks being persuaded to look the other way.

How good is Clarke? Quite good, I’d say. There’s no way to “like” the character he’s playing, of course, and the 48 year-old Clarke is 11 years older older than EMK was at the time of the tragedy. But the resemblance is nonetheless striking, and I bought what Clarke was doing and saying and feeling. Thank God he doesn’t overdo the Kennedy accent. The bottom line is that I believed that his EMK was in terrible pain that weekend, and I mean aching from the effort of trying to weasel out of a tough situation.

But Bruce Dern‘s performance as the legendary paterfamilias — the wheelchair-bound, stroke-afflicted Joseph M. Kennedy — is arguably the most searing, and all the more striking because he has no lines (he says one word over the phone — “alibi”) and does it all with his damning eyes plus a single slap across the chops. I can easily see some Best Supporting Actor action.

The depiction of Kopechne’s slow, agonizing death from suffocation inside Kennedy’s submerged, upside-down 1967 Oldsmobile is agonizing to read. The movie tones this scene down; I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t relieved. In the draft I read Kennedy and Kopechne kiss (on-camera) and even do the deed (off-camera). That’s been cut out.

The Chappaquiddick incident all but destroyed Kennedy’s reputation as a stable Presidential-timber type, but he gradually recovered. For nearly four decades after the tragedy Ted was a fully respected and renowned legislator, a Presidential candidate in 1980, an ally of former President Barack Obama and vice versa, a health care advocate, a godfather, a diplomat and an operator who knew how to play the game and get things done.

But after Chappaquiddick opens on 4.6.18, the name of Edward M. Kennedy will be sullied yet again. Due respect to those who tried to persuade Byron Allen to smother the film, but this is how it should be.

From Owen Gleiberman‘s Variety review: “Chappaquiddick is exactly what you want it to be: a tense, scrupulous, absorbingly precise and authentic piece of history — a tabloid scandal attached to a smoke-filled-room travesty. It recounts and anatomizes, with riveting detail, the tragic car accident and its aftermath that cast its shadow over the political career of Edward Kennedy and, in many ways, came to symbolize his existence. The movie is avidly told and often suspenseful, but it’s really a fascinating study of how corruption in America works. It sears you with its relevance and, for that reason, has every chance to find an audience.”