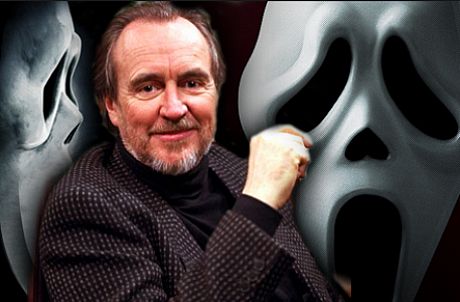

One of the coolest things about the late Wes Craven, who passed earlier today from brain cancer, was the way his name sounded like a low-rent villain in a drive-in movie. The sound of it spoke to the slimier, spookier regions of the human soul — craven being synonymous with “cowardly, lily-livered, faint-hearted, chicken-hearted, spineless, pusillanimous” and rhyming of course, with Edgar Allen Poe‘s “The Raven.” Nothing good could come of such a name or a man using it, you might have thought, and yet Craven became a major horror-exploitation figure in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s and wore the crown of being the most influential fright maestro in Hollywood’s second-tier realm.

Craven’s career highlights included The Last House on the Left (which Roger Ebert described when it opened in 1972 as “a tough, bitter little sleeper of a movie that’s about four times as good as you’d expect”), The Hills Have Eyes (’77), the original Nightmare on Elm Street (’84) and the whole unfortunate Scream franchise of the mid ’90s and beyond, which made Craven very rich.

Craven also directed Vampire in Brooklyn, The Serpent and the Rainbow, The People Under the Stairs, Cursed, Red Eye and My Soul to Take.

How did Craven manage to direct Music of the Heart, a 1999 Meryl Streep film of Roberta Guaspari, co-founder of the Opus 118 Harlem School of Music? Politically, I mean. How did he swing it? That was always a curiosity.

Read more