Posted today (3.8) by Jeff “Insneider” Sneider:

Posted today (3.8) by Jeff “Insneider” Sneider:

I felt underwhelmed by Errol Morris‘s CHAOS: The Manson Murders (Netflix, now streaming). It’s minor Morris — a skeptical-minded, 96-minute documentary that fiddles around with Tom O’Neill and Dan Piepenbring‘s “CHAOS: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties“.

The book is a nonfiction speculation about how the Manson horrors may (emphasis on the “m” word) have been subtly triggered or egged on or possibly even orchestrated by “Jolly” West, an apparently sinister figure with ties to the CIA and the MKUltra project in particular.

The film is basically about the white-haired O’Neill (no, not the squishy Oscar prognosticator Tom O’Neil) trying to sell Morris on his theories and suspicions about West, and Morris asking many, many questions and gradually coming to believe that the West-Manson legend isn’t all that credible.

I feel the same way.

The Manson malice happened in part because of a surreal, over-the-waterfall psychology that took hold among alienated middle-class youths who had sampled psychedelia and took the proverbial cosmic plunge, and especially among a few impressionable ditzoids who populated the Manson family in ‘68, ‘69 and, for a few, well beyond.

Charlie Manson was a crafty, headstrong, drillbit sociopath and a half-decent singer-guitarist who wanted to be a rich and famous rock star, but couldn’t quite pull it off. Manson knew deep down that all of his spiritual guru sermons and posturings were more or less a bullshit side activity.

It’s fascinating to consider some of the particulars about Manson’s interactions with Dennis Wilson and Terry Melcher, and how one night Manson even jammed with Neil Young.

Late last night I attempted a re-watch of Blake Edwards‘ S.O.B. (’81), which I was amused and moved by way back when. It’s an inside-Hollywood satire that feels somewhat realistic (Edwards seemed to be going for broke with this one) and was stocked with roman a clef characters (Robert Vaughn as Bob Evans, Marisa Berenson as Ali McGraw, Shelley Winters as Sue Mengers, etc.)

From the mid ’60s onward Edwards had been a celebrated slapstick guy, of course. People actually liked the fact that his films were broad and over-performed. But S.O.B. really didn’t work for me yesterday, and I distinctly recall writing a positive review in late ’81 for The Film Journal, for which I was the managing editor. That was then, this is now. S.O.B. is bruising.

HE’s 12.15.10 obit: I’ve always found most of Edwards’ stuff laborious, in part because so many of his films (certainly beginning in the early ’70s) exuded a square establishment sensibility. A respected auteur, surely, but I always sensed the attitude of a schmaltzy, well-paid, Malibu-colony type of guy.

I never sensed, in short, that Edwards’ film were about anything more than (a) the fact that he had a certain instinct for comic timing and orchestrating pratfalls, a gift that arguably put him in the same realm as Mack Sennett (but nowhere near that of Buster Keaton), and (b) that he enjoyed livin’ the high life and therefore felt compelled for some reason to stock his films with evidence or reflections of this. And I always hated the way his films were lighted and shot in a typical big-studio “house” style.

Edwards had a good run with Peter Sellers, of course, but Sellers’ greatest director friend/ally was Stanley Kubrick, not Edwards.

There are only two Edwards films I really and truly admire (as opposed to liking or tolerating), and they’re (a) both San Francisco-based and (b) were released in ’62. Numero uno is Experiment in Terror (’62), a creepy no-frills noir about a terrorized bank teller (Lee Remick) and an FBI guy (Glenn Ford) trying to protect her. The other is the legendary drama of alcoholism, Days of Wine and Roses, with Jack Lemmon and Lee Remick.

The Edwards films I regard as “fine,” “okay” and/or “relatively decent” are Breakfast at Tiffany’s (except for Mickey Rooney‘s awful performance), A Shot in the Dark (moderately funny at times), The Party (some brilliant portions), Wild Rovers (decent western), 10 (overrated but funny at times), What Did you Do in The War, Daddy? (’66) and the low-budget That’s Life (Jack Lemmon facing old age and male menopause depression — honest and decent).

Five days ago I posted a “Friendo confidential” about the tragedy that happened at the Hackman-Arakawa abode in mid February. It very closely mirrored what New Mexico authorities officially reported yesterday at a Santa Fe press conference.

Upon posting the 3.3 friendo tip, HE reader “Thomas B.” commented as follows:

This is my daily life…dogged by scolds and piss-hounds.

The beginning of the end of Chumash culture happened in 1769, when the first Spanish soldiers and missionaries arrived in Southern California with the intent of Christianizing the natives and facilitating Spanish colonization.

And then the mean-ass Mexicans arrived in the mid 1830s, and life for the Chumash natives became even worse. The Chumash were driven off the land and enslaved by the new administrators. Many found “highly exploitative” work on large Mexican ranches. After 1849, most Chumash land was lost due to theft by Americans and a declining population, due to the effects of violence and disease.

In 1855, a small parcel of land (120 acres) was set aside for just over 100 remaining Chumash Indians near the Santa Ynez mission. This land ultimately became the only Chumash reservation, although Chumash individdles and families continued to live throughout their former territory in southern California. The Chumash population was between roughly 10,000 and 18,000 in the late 18th century. In 1990, 213 Indians lived on the Santa Ynez reservation.

Nothing lasts forever. The Chumash had their era, and then it ended.

Why is this harmless New Rules video age-restricted?

Thank God I don’t have to hate on The Brutalist any more. The debate’s over and nobody of any weight or wisdom or professional merit will want to discuss it ever again. Consigned to history’s dust bin.

Whatever the Brutalist want-to-see factor might have been, it was pretty much suffocated by Adrien Brody‘s six-minute acceptance speech. So many millions of viewers were muttering “good heavens, shut up…just shut the fuck up.” If only Timothee Chalamet or Ralph Fiennes had won…

On the other hand it’s not fair to put Brody down over the chewing-gum toss. Before watching the below video I hadn’t realized that Brody’s age-appropriate g.f. Georgina Chapman emphatically told him, gesture-wise, to throw the gum her way.

Arthur Penn‘s surreal Mickey One (’65) is a black-and-white low budgeter about a hunted, haunted stand-up comic (Warren Beatty) on the bum in Chicago. It’s about paranoia and loneliness and how the game is rigged against the individual. It feels a bit coarse and splotchy at times, but it’s also a kind of loose-shoe, catch-as-catch-can arthouse whatsis with a kind of French nouvelle vague or Italian neorealist vibe (can’t decide).

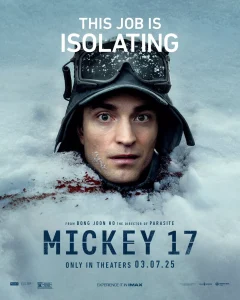

Is Mickey One a better film than Bong Joon-ho‘s Mickey 17? I never liked Penn’s film all that much, but it feels like a raggedy-ass masterwork compared to the latest Mondo Bongo.

Mickey One is about something that we’ve all sensed or feared at one time or another (i.e., the world is run by predators). Mickey 17 is a woke instructional about the necessity of feeling compassion for society’s lessers or outcasts. Mickey One is an in-and-outer but it’s thematically relatable (at least to existential lone-wolf types). Mickey 17 is about Bong banality.

Martin Scorsese and Isabella Rossellini were married from 1979 to 1982, or during his period of cocaine withdrawal + Raging Bull rebirth, followed by The King of Comedy and the anxiety, uncertainty and commercial failure that provided accompaniment.

The response to New York, New York (’75), one of the biggest cocaine movies of all time + a film that Pauline Kael called “an honest failure“, drove Scorsese into depression.

Wiki: “By several accounts (Scorsese’s included), De Niro saved Scorsese’s life when he persuaded him to (a) kick coke and (b) make Raging Bull.

“Mark Singer: “Marty was more than mildly depressed. Drug abuse, and abuse of his body in general, culminated in a terrifying episode of internal bleeding. De Niro came to see him in the hospital and asked, in so many words, whether he wanted to live or die.

“If you want to live, De Niro proposed, let’s make this Jake LaMotta picture.” Artistic adulation and Oscar glory resulted. Then came The King of Comedy (’82).

No marriage could have survived Scorsese’s ’79 to ’82 period.

The Guardian‘s Simon Hattenstone: “After they separated, Marty told Isabella it had been important to him ‘to think that he was in a relationship with Roberto Rossellini’s daughter.’ Family history repeated itself when she and Scorsese divorced; by then, she was pregnant with another man’s child — that of the former model Jonathan Wiedemann.”