Yesterday Variety‘s Owen Gleiberman posted a piece about what he describes as obsessive fanboy worship of Ridley Scott‘s Blade Runner, and how that purist fervor found its voice in Blade Runner 2049.

The key element in Scott’s 1982 original, Gleiberman argues, “is its transcendental mystique — the fact that it now plays like the sci-fi blockbuster equivalent of slow food. Its storytelling longueurs have been inflated into the very signifiers of its artistry. It has become not just a movie but a symbol: the anti-Star Wars.”

Key observation: “I remain a fan of Blade Runner, but to be in the cult of Blade Runner is to celebrate the purity of its vision, and to join in a conspiracy theory about the forces that would obliterate that purity.” Gleiberman doesn’t specifically call director Denis Villeneuve a cultist, but he kinda does.

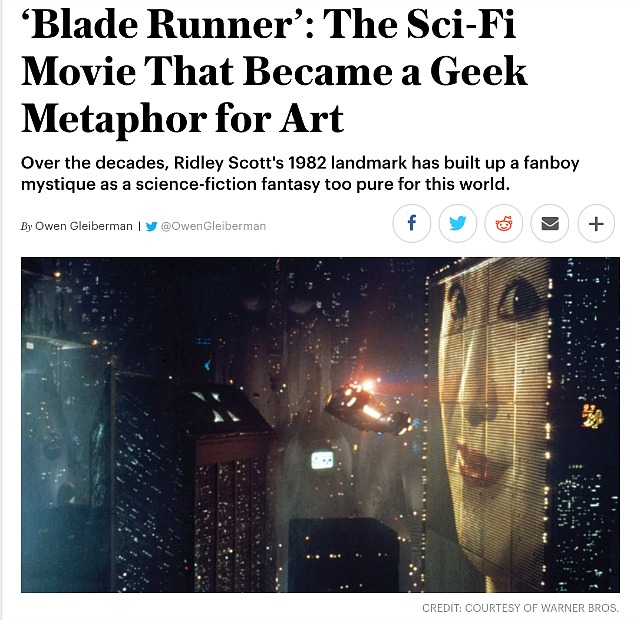

My argument with the piece is in this passage: “[Scott’s Blade Runner was] a majestic science-fiction metaphor, beginning with its opening shot: the perpetual nightscape of Los Angeles in 2019, the smog turned to black, the fallout turned to rain, the smokestacks blasting fireballs that look downright medieval against a backdrop of obsidian blight. Blade Runner wasn’t the first — or last — image of a desiccated future, but it remains one of the only movies that lets you feel the mechanical-spiritual decay.

“There’s a touch of virtual reality to the way we experience it, sinking into those blackened textures, reveling in the details (the corporate Mayan skyscrapers, the synthetic sushi bars, the Times Square-meets-Third World technolopolis clutter), seeing an echo of our own world in every sinister facet.”

But how much of an echo? Scott’s film was a noirish ecological forecast of where we all might be headed, and I fully understand that vision-wise there’s no upside to low-balling whatever horrors the future might bring. But at the same time if you’re predicting…okay, imagining a world as horrific as Blade Runner‘s from a 1982 vantage point, or 37 years into the future back then, shouldn’t you have to pay some kind of piper if your vision has been proven to be way, way off? If what you foresaw hasn’t even begun to manifest?

Scott’s Blade Runner milieu — nightmarish, gloom-ridden, poisoned — is obviously a trip in itself and fun to wallow in, but it was set less than two years from today, in 2019, and as I said last weekend the sprawl of real-world Los Angeles has exposed that realm as absolute noir-fetish fanboy bullshit.

“Blade Runner 2049 is, of course, a prophecy of ecological run to come, and that’s where we’re definitely heading with criminals like Scott Pruitt running the EPA,” I wrote, “but BR49‘s idea of what Los Angeles will look like 32 years hence is almost surely just as ludicrous as Scott’s.

Does this mean anything to anyone? Nope. Irrelevant. The twin Blade Runner realms have sunk their visions into our heads and will probably never be dissipated. But facts are facts. Los Angeles of 2017 doesn’t bear the faintest resemblance to Ridley Scott’s noirish nightmare city. Because 35 and 1/2 years after the release of Scott’s film, there’s very little in the way of “Times Square-meets-Third World technolopolis clutter” here, even in the caverns of Little Tokyo or Chinatown. Okay, I’ve been to a couple of synthetic sushi bars (there’s one adjacent to the Hollywood Arclight) and things are far from perfect here, but otherwise it’s a relatively clean and tidy town in which “everybody very happy ‘cause the sun is shinin’ all the time.” Or at least, that was the vibe last Saturday.

George Orwell’s 1984 wasn’t validated by reality 33 years ago, but it’s been semi-validated since, at least as far as everyone having lost their privacy and paying obsessive attention to Big Brother-ish Twitter banshees doing their level best to intimidate, condemn and control. The projections in H.G. Wells and William Cameron Menzies‘ Things To Come (’36) were validated in some ways, at least. [See Trailer From Hell essay below.) But the Los Angeles of 2017 wasn’t even slightly captured by Scott’s toxic metropolis. Air quality and Long Beach oil refineries aside, there isn’t even a coincidental depiction that rings true today.

The real visionary, it turns out, was Randy Newman, who might not have written “I Love L.A.” as a response to Blade Runner, but he certainly could have. Blade Runner opened on 6.25.82 — Newman’s “Trouble in Paradise” album (which “I Love L.A.” was the most famous cut from) popped seven months later, on 1.25.83. There isn’t a single sincere line in the most iconic Los Angeles anthem of all time, but every now and then the sun does shine and the skies are cloudless and bright blue, and everybody seems to be on the same good-vibes wavelength.

So where has the Blade Runner universe actually come from? From legitimate fears of industrial ruination, of course, but also from the despairing, fatalistic moods and attitudes that once resided inside Philip K. Dick, Ridley Scott, Hampton Fancher, David Peoples, Jordan Cronenweth, and, one could argue today, from the devotional geeks who regard the handed-down Blade Runner vision as absolute gospel, and have now made a film about that devotion.