The basic import of Susanna Nicchiarelli‘s Nico, 1988 (Magnolia, 7.4) is that the legendary ice-cool Nico — deep-voiced, stone-faced, Teutonic doom-chanter — was a greater artist in her heroin-habit decline period (late ’70s to late ’80s) than she was in her breakout period (mid ’60s to early ’70s). And that’s fine — a valid analysis of her songwriting and performing career.

But the film itself is slow, irksome, repetitive, sometimes vague and too often dull. Nicchiarelli makes her points, but the beat-by-beat watching of this 93-minute film is mostly unsatisfying. To me anyway. I checked my watch four or five times.

Everything I’ve always loved about Nico, musically-speaking, was the stuff she was unhappy with. She said over and over that her true musical identity and vision came into being only after her late ’60s Velvet Underground phase (“Femme Fatale”, “All Tomorrow’s Parties”, “I’ll Be Your Mirror”) and after “Chelsea Girl“, which she hated the arrangements for.

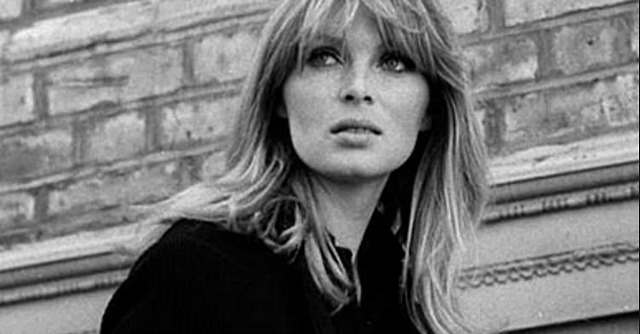

Heroin-habit Nico in 1985.

So fine — Nico only came into her own when she started writing and performing her own gloom-rock material. I’m sure that was true. Except I’ve never listened to her gothy downswirl stuff, but I love “Chelsea Girl” and the 1967 banana album. Does that make me a serf or an asshole? I don’t think so.

Last September the Venice Film Festival elite creamed over Nico, 1988, but what else is new? You can’t trust critics when it comes to personal-vision indie cinema because they almost always give films like Nico, 1988 a pass, in part because they don’t want to be the naysaying stand-out. Maybe you can’t trust Hollywood Elsewhere either, but at least I deal straight cards.

Nico, 1988 is more into moods and atmospheres than particulars and specifics, and so the first thing you do after it’s over is go online to learn what actually happened on a chapter-by-chapter basis. That’s what I did after it ended. Only after I read everything about Nico’s declining years did the film start to come together in my head.

There’s a short scene in which Nico and her band visit the site of the Nazi rally grounds in Nuremberg but Nicchiarelli doesn’t want to identify the location because that would be tedious and unhip, and so it becomes a scene about the band visiting an old concrete stadium of some kind…who cares? The whole movie is like that. You can feel or least sense what’s happening, but Nicchiarelli often declines to fill in the blanks.

Nico’s life ended in ’88 while staying in Ibiza. She suffered a heart attack, fell off a bicycle, hit her head and died of a cerebral hemmorhage. Nichiarelli doesn’t depict this, of course, but you can’t help but wonder “well, why not?”

The film tells us that Nico’s son Ari (his father was Alain Delon) tried to kill himself while the band was on tour. Ari had a heroin problem of his own, but the film provides no hint as to why he would try to off himself, and there’s nothing online that mentions a suicide attempt. It just happens and then he recovers. So why did…forget it, sorry I asked.

Tryne Dyrholm gives an arresting, at times darkly amusing performance as the aging chanteuse. But she doesn’t have Nico’s beautiful swimming-pool eyes or killer cheekbones. Even when she put on weight and dyed her hair black, the real McCoy always struck me as a moderately sexy junkie or at least a junkie who used to have that foxy X-factor allure. Dyrholm kicked that pleasant memory right out of my head, and in fact killed it. She’s just too bulky and bloated. In my mind there was no way she could even be Nico’s second cousin.

Search the real-life Nico photos, and in 98% of them she’s really fascinating. You just wanted to stare and stare at her. But not Dyrholm. I actually wanted to look away after a while. She doesn’t look like a Teutonic goddess gone to waste, but like a fat junkie (which is how Andy Warhol described Nico at one point in the ’80s). I enjoyed her German-accented speaking voice but the “alluring Nico” thing is missing. It’s like watching the Network-era Ned Beatty portray the 50ish Cary Grant.

And the cigarettes! I have a formula worked out, and it’s this: the more a character relentlessly medicates with tobacco, the worse the film is. Halfway through I was ready to stand up and shout at the top of my lungs “JESUS H. CHRIST, WILL YOU GIVE THE CIGARETTES A REST?”

The best moment of the film may be the very first — the sight and the rumble of far-away Berlin being bombed, with the five- or six-year-old Nico (her real name was Christa Paffgen) and her mother talking about the destruction.

The second best moment depicts a concert that Nico and her band gave in a small hall in Prague, sometime around ’87. Angry and without heroin, Nico/Christa sings her soul out…really belting the lyrics for all they’re worth. You can feel the connection, the fulfillment. A moment to hang onto.

I was in Prague in October of 1987, and I remember how quiet and spooky things were at night. No crowds, no hurly-burly, next to no commercial street signs, not even street lamps…just darkness and cobblestones and grim silence.