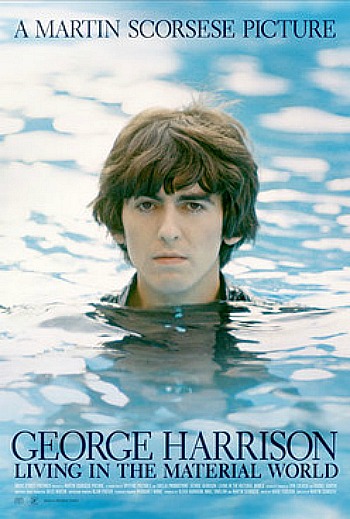

Yesterday’s announcement about HBO acquiring North American TV rights to Martin Scorsese‘s George Harrison: Living in the Material World for an early October airing was thin on particulars. So here’s something no one’s reported thus far, and which I got this morning from a source in the office of HBO’s Sheila Nevins: the Harrison doc has an “approximate” running time of 210 minutes.

In other words, it’s almost exactly the same length as Scorsese’s Bob Dylan: No Direction Home, which runs 208 minutes. This explains HBO’s plans to air Scorsese’s film in two parts on HBO on Wednesday, 10.5, and Thursday, 10.6.

The Harrison doc will almost certainly follow in the Dylan doc’s footsteps by showing at the 2011 Toronto Film Festival. No Direction Home premiered at the 2005 Toronto Film Festival.

The editor on the Harrison doc is David Tedeschi, who also cut No Direction Home as well as Scorsese’s Public Speaking, the Fran Lebowitz doc, and Shine a Light, the 2008 Rolling Stones’ concert doc.

Todd McCarthy noted in his review of No Direction Home that it was similar in structure to the 216-minute Lawrence of Arabia in that Part One was all about the rise (inspiration, struggle, adventure, glorious success, sitting on top of the world) and Part Two was about the fall (complications, defeats, psychological doubt and turmoil, despair).

This suggests, given the three-and-a-half-hour length and the Scorsese-Tedeschi collaboration, that Part One of the Harrison doc (which is expansive enough overall to be called Harrison of Liverpool) will also end on a youthful, triumphant, top-of-the-mountain note. An honest assessment of the last 34 years of Harrison’s life (’67 to ’01) would hardly characterize them as dour or downfall-ish. But they were certainly different and in some ways darker (i.e., more complex, textured, mixed-baggy, adult, meditative) than the rush-and-climb years (’43 to ’67).

I’m guessing that Part One will most likely cover Harrison’s first 25 years, or from his birth on 2.24.43 and through his youth and teenaged years and into the first seven years of the Beatles (’60 to ’67), and probably ending with the Revolver and Sgt. Pepper period, which marked the initial stirrings of Harrison’s interest in Indian music and his identity starting to take shape as the serious, glum-faced guy whose guitar playing had a sad, weeping quality, and who wrote many songs from ’67 through the early ’70s that essentially lectured and admonished listeners for being shallow and distracted and missing the spiritual boat.

I’m also presuming that Part Two will most likely begin with Harrison’s solo career launching with the Beatles breakup, the making of All Things Must Pass, the 1971 Concert for Bangla Desh, etc. And then settling into the mid to late ’70s and ’80s, “Crackerbox Palace,” Handmade Films, the Travelling Willburys, the stabbing incident and so on.

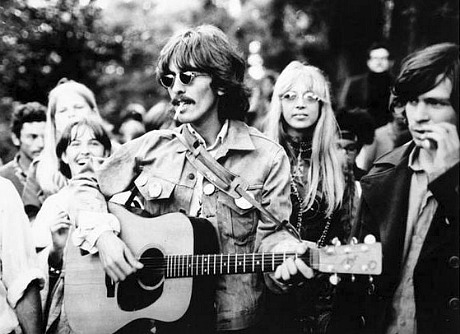

Beatle lore-wise, Harrison was regarded early on as the solemn one, the deep spiritual cat (i.e., the last one to leave Maharishi Mahesh Yogi‘s ashram in Indian in late ’67) and to some extent the political commentator and satirist (the lyrics of “Piggies” and “Savoy Truffle“, “the Pope owns 51% of General Motors,” etc.).

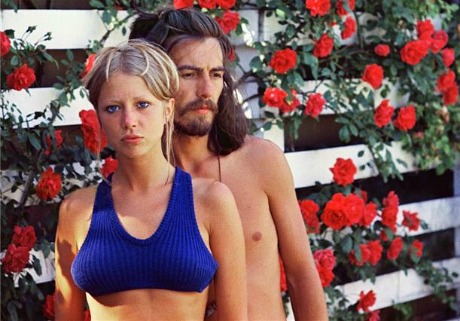

Read this account of George and Patti Boyd Harrison’s brief August 1967 visit to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashubry district, which by that time was the pits.

I also remember a story in an anonymous groupie tell-all book about a girl giving Harrison a blowjob while he played the ukelele, and after it was over his getting up and saying “thanks, luv!” and leaving the room without asking her name. Funny.

Harrison died of lung cancer at age 58 on November 29, 2001, in Los Angeles. His Wiki bio says “he was cremated at Hollywood Forever Cemetery and his ashes were scattered in the Ganges River by his close family in a private ceremony according to Hindu tradition. He left almost 100 million pounds in his will.”

Scorsese, who’s been working on the Harrison doc since ’08, has said that “the subject matter [of Harrison’s life] has never left me…The more you’re in the material world, the more there is a tendency for a search for serenity and a need to not be distracted by physical elements that are around you. George’s music is very important to me, so I was interested in the journey that he took as an artist. The film is an exploration. We don’t know. We’re just feeling our way through.”