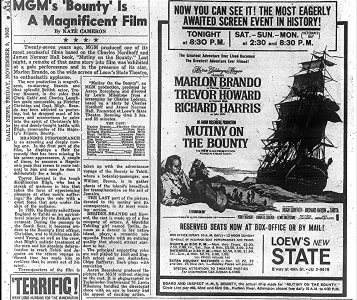

Hollywood’s second version of Mutiny on the Bounty opened on 11.8.62, or ten days after the conclusion of the tension-filled Cuban Missile Crisis.

This almost felt like a fitting crescendo as the film was widely regarded as a crisis itself, albeit a “what the hell happened?” kind. The final production tab was $27 million, or roughly $275 million in 2023 dollars — a startling level of exorbitance.

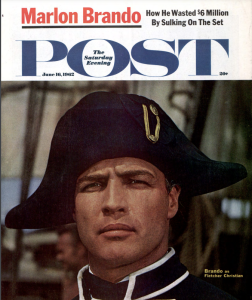

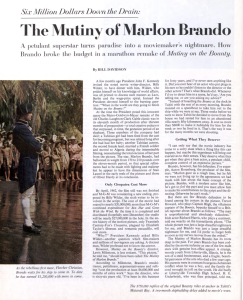

Bounty had been shooting for two years, partly under the directorial command of Sir Carol Reed but mostly Lewis Milestone, who didn’t get along wih star Marlon Brando and vice versa. A few months earlier the film had been publicized as a cost-overrun disaster, particularly by a June 1962 Saturday Evening Post cover story, written by Bill Davidson, that identified Brando as the principal culprit.

Production was marked by constant tempest (Reed either quit or was let go, and Milestone, his successor, also left under turbulent circumstances), largely, according to Davidson, due to Brando’s egoistic big-star behavior. Brando sued the Post for $5 million over claims that the article had wrongfully damaged his professional reputation. It did, in fact, do that.

Filming was almost as prolonged and costly as the $31 million Cleopatra, which would open seven months later in June 1963.

I wouldn’t call Mutiny on the Bounty a flawed film as much as a “good but not quite there” one. It’s actually a well-written, handsomeiy produced, eye-filling wow for the first 70% or 75%, and Bronislau Kaper‘s score is inescapably rousing in a crash-boom-bang sense.

I would give it an 8.5 grade up until and including the mutiny sequence. But the tension flies out the window after the mutiny, and the remainder of the film is just okay. And Brando’s (i.e., Fletcher Christian‘s) high-minded urging that he and the crew should return to England to plead their case? Totally absurd. Tantamount to suicide. I agree with the decision by Richard Harris‘s Mills and other crew members to burn the ship after Brando suggests this hair-brained notion.

The act that ignites the mutiny scene as Brando’s Fletcher Christian tries to give fresh H20 to a thirsty seaman, and Howard’s Cpt. Bligh expresses his opposition.

Say what you will about Bounty‘s problems — historical inaccuracies and inventions, Brando’s affected performance as Christian, the floundering final act. The fact remains that this viscerally enjoyable, critically-dissed costumer is one of the the most handsome, lavishly-produced and beautifully scored films made during Hollywood’s fabled 70mm era, which lasted from the mid ’50s to the late ’60s.

It has a flamboyant “look at all the money we’re spending” quality that’s half-overbaked and half-absorbing. It’s pushing a certain pounding, big-studio swagger.

There’s a way to half-excuse Bounty for doing this. It was made, after all, at a time when self-important bigness was regarded as a kind of aesthetic attribute unto itself, with large casts, extended running times, dynamic musical scores (overtures, entr’actes, exit music) and intermissions all par for the course. And there’s no denying that a lot of skilled craftsmanship and precision went into this manifestation.

Bounty definitely has first-rate dialogue and editing, and three or four scenes that absolutely get the pulse going (leaving Portsmouth, rounding Cape Horn, the mutiny, the burning ship). And I happen to like and respect Brando’s performance — it gets darker and sadder as the film goes along — and you can’t say Trevor Howard‘s Captain Bligh doesn’t crack like a bullwhip. (Bosley Crowther‘s review said his emoting was imbued with “wire and scrap iron”, and that Brando’s came from “tinsel and cold cream”.) And Richard Harris and Hugh Griffith are fairly right-on. And everybody likes the topless Tahitian girls.

I’d forgotten how foppy and buffoonish Brando’s Fletcher Christian character is, and how frequently his contentious relationship with Trevor Howard‘s Captain Bligh is played for easy laughs during the first 100 minutes.

The extremely wide 2.76 to 1 Ultra Panavision image, shot by Robert Surtees and derived from the original 70mm elements, is really quite beautiful, and the colors are full and luscious.

My difficulties with the jokey humor aside, I have to acknowledge the “make love to that damn daughter of his” scene between Howard and Brando, and pay my respects to the way Brando pauses ever so slightly before and after he says the word “fight”. It’s the film’s wittiest moment — the only line that still makes me laugh out loud.

The decision not to offer a “making of” documentary on the Bounty Bluray was unfortunate, given that Mutiny on the Bounty‘s production history was one of the most expensive and out-of-control in Hollywood history, and therefore worth recounting for history.

Fox Home Video included an ambitious making-of-Cleopatra doc along with their Cleopatra disc, and it’s a far more engaging thing to watch than the film itself. Too bad Warner Home Video didn’t follow suit. Laurent Bouzereau or someone on his level could’ve really gone to town with it.