Let’s pretend that Bill Murray got hit by a truck yesterday and that it’s time for an obit. If I had an hour to grind one out I would insist that the most glorious year of Murray’s life happened 31 years ago — 1993 — when he delivered his two greatest performances — a sardonic Chicago loan shark named Frank “The Money Store” Milo in John McNaughton and Richard Price‘s Mad Dog and Glory, and a sardonic TV weatherman in Harold Ramis‘s Groundhog Day.

Murray was around 42 when he shot both.

Murray”s third-best performance happened five years later in Wes Anderson‘s Rushmore, in which he played Herman Blume, a wealthy Houston businessman (also sardonic) who falls in love with a grade-school teacher (Olivia Williams), and in so doing ignites a feud with a 15 year-old romantic rival, Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman).

Some thoughts about Milo, which I posted three years ago:

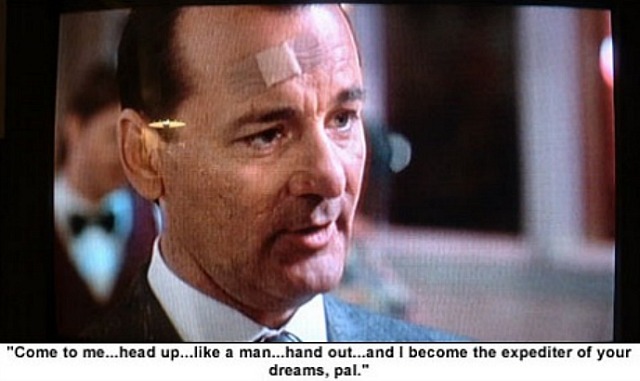

“Mad Dog and Glory is about a curiously touching friendship between Milo and Robert De Niro‘s Wayne — a timid, lonely Chicago cop who specializes in forensics and crime-scene photographs. Milo is a Chicago mob guy who becomes a big brother and ‘friend’ of Wayne’s after the latter saves his life.

“Milo is a lot like Murray in many ways, just not internally. He’s angry and doesn’t really like himself or his friends or his life. He wants to be somewhere else. He’s seeing a therapist to try and deal with the hostility, and he performs a stand-up comedy routine at a place called the Comic-Kaze Club, which he owns. But he doesn’t want to lose the gangster life either.

“Frank and Wayne’s connection begins when Wayne — joshingly called “‘Mad Dog’ by his cop pals — saves Frank’s life during a grocery store holdup by calming down a jittery holdup man and sending him away without bloodshed.

“Frank is initially appalled (‘You’re a cop?’), but the next evening, realizing what Wayne actually did and starved for a friend, Frank tries to reciprocate by getting friendly over drinks. The next day he sends Glory, who works at the Kamikaze Club, over to Wayne’s place, the idea being for her to stay with him and take care of whatever for seven days.

“The wrinkle comes when Wayne and Glory fall in love, and Wayne decides he doesn’t want her being Frank’s ‘favor girl’ any longer. But Frank won’t let her go (Glory has offered her services in order to save her brother from being killed over a debt) unless Wayne coughs up $40K…fat chance.

“The theme of the film is, basically, ‘no guts, no glory.’ That sounds like macho crap, but it’s well sold.

“I don’t know where Price’s script ends and Murray’s improvs begin, but Mad Dog and Glory is full of little Murray doo-dads. There’s his lounge-lizard rendition of ‘Knock Three Times,’ crooned at the beginning of a tense scene. His addressing De Niro as ‘ossifer’ (a term I hadn’t heard since I was a kid in New Jersey). The way he holds an air bugle to his lips and does a cavalry-charge bugle sound when De Niro’s cop friends come to his rescue at the finale.

“There’s a scene in a diner in which Frank’s intellectually challenged top goon, Harold (Mike Starr), who’s sitting nearby with a supermarket tabloid, points at a middle-aged man sitting at the counter and whispers to Milo, ‘Hey, Frank? Isn’t that Phil Donahue?’ A shot of the guy in question proves otherwise. Murray half turns in his seat and says, ‘Put the magazine down, Harold, before you hurt yourself.’

“Consider the melancholy in Murray’s eyes after his fight scene with De Niro at the finish. Frank is a predator, yes, but a bright and sometimes funny one, and the tragedy of his life is that he wants out and knows he won’t get there. He pulls a loose tooth out of his mouth, gestures at the gaudy Cadillac he’s sitting in and the gorillas he’s riding with, and says with a look of pure disgust, ‘This is my life.'”