Tribute and Testament

The late Richard Sylbert, one of the most gifted production designers in Hollywood history and a guy I was proud and very delighted to know, wrote a 200-page chronicle about part of his career before passing away in March 2002. Five or six years ago journalist Sylvia Townsend offered to edit what Sylbert had written. That never happened, but a year after he died his widow, Sharmagne Leland-St. John-Sylbert, cut a deal with Townsend to finish what Sylbert had begun and also fill in the missing pieces — i.e., to create a combination biography- autobiography.

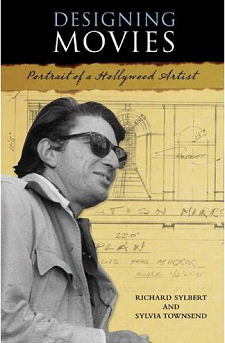

The result is “Designing Movies” Portrait of a Hollywood Artist” (Praeger), a finely written history and an elegant tribute to a great man. But before getting into the substance of it, there’s some mucky-muck about authorship and credit-hogging that needs clearing up.

The front cover tells us that “Designing Movies” was written by Sylbert and Town- send. That’s a completely accurate statement. And yet on the inside front flap it says the authors are these two “with Sharmagne Leland-St.John-Sylbert,” who wrote only an “afterword” chapter. Sylbert’s widow also arranged for an insertion of a brief bio of herself along with Sylbert and Townsend on the inside back flap. Townsend, whom I spoke to Thursday night, told me a lot about Sharmagne Leland-St. John-Sylbert’s maneuvers over the last three years. Suffice that she inserted herself into the interview process to no discernible benefit to the book, and she often generated questionable claims and assertions that were later shot down during fact-checking.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

And yet Sylbert’s widow has elbowed herself into the promotion of this book, and will be the one signing copies at a Book Soup event on Sunday, 10.29 at 4 pm. I gather Townsend will be elsewhere. I hope that this won’t dissuade anyone from dropping by and picking up a copy — it’s a robust and worthwhile read — but arro- gance and egotism of this sort needs to be recognized.

Townsend worked on the book for three years. She edited and added material to 13 chapters that Sylbert had written, covering the beginnings of his career in the 1950s and leading up to his work on The Graduate, Carnal Knowledge and China- town; Townsend wrote another nine (covering, among other films, Shampoo, Reds, The Cotton Club and Dick Tracy) plus an “introduction to Richard Sylbert” chapter. The result is a fascinating ride through the Hollywood glory days of the ”60s, ’70s and early ’80s — a candid, pungent, wonderfully detailed tour.

I don’t mean absolutely candid. Sylbert was a character and as we all know, char- acters have their curiosities. I loved his brilliance, his bluntness, his perceptions — he’d worked with everyone and was a great racounteur. But he was a bit of a bull- shitter, he wasn’t the most serene man in the world, and the ’60s sand ’70s were known for colorful behavior. It’s clear that Townsend has composed a very thorough study of a very complex man, and yet she hasn’t tried to mine the turf of Peter Biskind‘s “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls” — it’s an honest book, but far from a tell-all. But I didn’t read Townsend’s book in search of exotic tales. I wanted to revisit the life of a very gifted fellow, and on this level it fully satisfies.

In the few years that I knew him, I thought of Sylbert as a friend and a great source, and perhaps the greatest teller of Hollywood stories I’d ever been lucky enough to know. Every time we spoke he’d toss off a recollection or two about this or that heavyweight he’d known and worked with over the last 40-odd years, and I’m speaking of every top-ranked talent over the age of 50 who’s ever had a creative impact on this town — Warren Beatty, Robert Towne, Robert Evans, Jack Nicholson, Julie Christie, Dustin Hoffman, John Huston, Elaine May, Francis Coppola, Richard Gere, etc.

Sylbert wasn’t just an intimate witness but a first-class participant in Hollywood’s great creative ferment of the late ’60s to early ’80s. For him, production design was always about more than just dreaming up the look of a film — he was a conceptual collaborator whose input, he always claimed, went far beyond visual apppearance. I know that on a design level alone his creations — which first appeared in Nicholas Ray‘s Wind Across the Everglades (1958) and had their swan song with P.J. Hogan‘s Unconditional Love — were always striking and every so often were wondrous.

Sylbert designed the edgy, sometimes vaguely hallucinatory sets used for John Frankenheimer‘s The Manchurian Candidate (1962), worked with Saul Bass on that legendary title credit sequence for Walk on the Wild Side (also ’62), and imagined the somewhat rickety, constipated interiors of George and Martha’s home in Mike Nichols‘ Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (’66). He came up with the jungle-like, zebra- and tiger-skinned interiors in Mrs. Robinson’s home in The Graduate (’67), as well as the black-and-white design of Benjamin Braddock’s home in that landmark Nichols comedy.

He also designed Rosemary’s Baby (’68), including the before-and-after interiors of the Woodhouse apartment in Roman Polanski’s as well as those wonderfully spooky nightmare visions seen during that demonic seduction sequence. And he did exquisite work for Nichols again on Catch 22 (’70) and Carnal Knowledge (’71), followed by his services on John Huston‘s Fat City and Elaine May’s The Heartbreak Kid (both in ’72). Then came Roman Polanksi‘s Chinatown, which Sylbert enhanced with perhaps the most luscious (but at the same time, somber and moody) re-creation of 1930s art-deco atmosphere ever savored on-screen.

He rendered the 1930s once again in Nichols’ The Fortune, and then late 1960s Beverly Hills in Hal Ashby, Warren Beatty and Robert Towne‘s Shampoo (’74). He did a brilliant job of capturing pre-World War I New York City in Beatty’s Oscar-winning Reds (’81), and won an Oscar nine years later for delivering a physical world of primitive, comic-book proportions in Beatty’s Dick Tracy (’90). He also delivered convincing period milieus for Francis Coppola‘s The Cotton Club (’84) and Lee Tamahori‘s Mulholland Falls (’96).

He also designed P.J. Hogan’s My Best Friend’s Wedding (’97), Brian DePalma‘s Carlito’s Way (’93) and The Bonfire of the Vanities (’90), Robert Towne’s Tequila Sunrise (’88) and Jon Avnet‘s Red Corner (’97). I remember marveling at his re-creation of a portion of Beijing’s inner city for Red Corner, and then listening to him tell me about the nuts and bolts over a breakfast we once shared at Swinger’s Cafe on Beverly Boulevard.

Sylbert won two Art Direction Oscars during his career for his work on Dick Tracy (shared with Rick Simpson) and on Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. He was also nominated for his work on Reds, The Cotton Club and Chinatown.

On top of all the priceless dish he shared with me over the years (he always picked up the phone, and he never told me he couldn’t help), I’ll always be grateful for his agreeing to drive out to Woodland Hills and speak to a film class I was moderating in ’97. And I’ll never forget how he always wore the same African safari jacket, whatever the occasion. It was a crying shame when he left. I miss him right now. He was an excellent guy to know and have a drink with.