Paul Haggis‘s In The Valley of Elah (Warner Independent, 9.21 or 9.28) is more than just a respectable true-life drama, and a helluva lot more than the sum of its parts. I think it’s close to an epic-level achievement because it’s four well-integrated things at once — a first-rate murder-mystery, a broken-heart movie about parents and children and mistakes, a delivery device for an Oscar-level performance by Tommy Lee Jones, and a tough political statement about how the Iraq War furies are swirling high and blowing west and seeping into our souls.

The best films are always the ones that don’t seem to be doing all that much, but then gradually sneak up on you, laying groundwork and planting seeds and lighting all kinds of fires and feelings. Elah is one of these. It’s a damn-near-perfect film of its kind. There’s one moment at the very end that could have been played down a bit more (i.e., a little less on-the-nose), but others I’ve spoken to don’t agree. I’m trying to think of other potholes but they’re not coming to mind.

Elah isn’t some concoction, some tricks-of-the-trade movie that’s mainly about pushing buttons and playing audiences like an organ. It’s primarily about respecting real-life experience and refining this into art. Haggis’s screenplay is based on a true story that happened in the summer of ’03, and was first reported a year later in a Playboy magazine article by Mark Boal, called “Death and Dishonor.” It came from Boal interviewing Lanny Davis, a former U.S. Army M.P., about the death of his son, who had been reported AWOL following a tour of duty in Baghdad. Haggis bought the rights and created a somewhat fictionalized version, although he stuck to the basic bones.

So let’s not hear any carping about this being another bleeding-heart, anti-Iraq War movie by a Hollywood leftie — it happened. In fact, to hear it from Davis (whom I called the day after I first saw Elah on 6.19), the real story is even darker and more damning.

Elah has been screening for critics over the last two or three weeks, and I know it’s definitely skewing positive, but this is one of those times when I don’t care if everyone understands how good it is or not. All right, I do care because it’s nice to be agreed with and I want to see this film break the Middle-Eastern conflict curse (i.e., the U.S. moviegoer mentality that apparently doesn’t want to know about anything Iraq or Afghanistan-y, an attitude that arguably killed or severely damaged A Mighty Heart at the box office) but I know what this thing is and that’s that.

Forget Crash, or rather forget whatever resentments you might have about Haggis’s film taking the Best Picture Oscar from Brokeback Mountain. And forget the beefs about Haggis writing scripts that are too explicit and surface-y with not enough subtext. Elah, trust me, is a much better, more plain-spoken film than Crash was. It’s about real people, real hurt, real tragedy. My first thought after seeing it was that Warner Independent should show it to all the Crash haters in order to put that dog to bed.

Elah is one of those very rare birds that starts out like a what-happened? procedural you may have seen before, and before you know it it’s doing something extra, and then something else and then another thing altogether. Before you know it Haggis has four or five balls in the air, and when it’s over you’re heading out to your car and going, “Hmmm…yeah…wow.”

I was thinking at first that Elah resembles David Greene‘s Friendly Fire, a 1979 TV movie based on a true story about the parents of a Vietnam veteran cutting through red tape to find out how their son actually died. But before the what- happened-and-whodunit? story even gets going you can feel the undercurrent of grief in Jones, whose character, Hank Deerfield, is based on Lanny Davis.

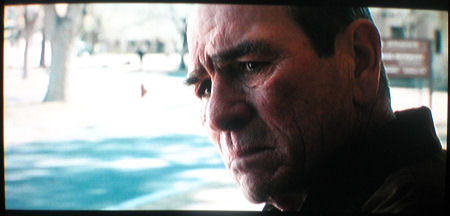

Jones’ weathered, old-guy face is full of the suppressed shock and grief and guilt that any parent feels when his or her son has gotten into trouble or otherwise done something inexplicable. And his performance, which is all about feelings being kept in check, like it always is with any old-school military guy, just keeps getting sadder and more affecting.

Haggis originally wanted Clint Eastwood to play Deerfield, but it’s a role that has Jones’ history and DNA all over it. He owns characters like Deerfield and that sheriff in The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, and the small-town sheriff he plays in Joel and Ethan Coen‘s No Country for Old Men, which comes out in November. All of them plain-spoken, craggy-faced Texas dudes with turkey necks, paunchy guts and wells of sorrow in their eyes.

The fact that In The Valley of Elah is a gripping investigative procedural is almost the least of its attributes. I felt I was swimming in holy water five minutes into it. Haggis’s early dialogue feels tight and true, and Jones and Sarandon’s acting in the early scenes feels like the playing of two master violinists. (There’s a sad phone call scene between them that choked me up, and Sarandon has a flash- of-rage moment that pierces right through). Add this to Roger Deakins‘ cinema- tography and Jo Francis‘s editing, and any half-aware observer can tell from the get-go that this is very high quality stuff. You just know it. You can feel it happening a hundred different ways.

Red-staters and blue-staters alike are going to get where this film is coming from — they’re going to feel it in their hearts, and make all the connections on their own without going off into specific tirades or defenses.

It’s not so much Haggis-the-Hollywood-liberal as the story itself that’s making the point here, which is that the Iraq War is primarily responsible for the terrible thing that this film turns on. It’s heartening to hear (as Jones’ character says at one point) that David sometimes does win out over Goliath — the title refers to the valley in Israel where their ancient conflict took place — but the Iraq War is a thousand plunderers and a thousand knives. It is obviously laying waste left and right, and will continue to do so for a long time to come, and for what?

(Iraq is going to suffer a blood bath — maybe like Ireland, maybe like Rwanda — and eventually break apart like Yugoslavia and become two or three countries. People have to tend their own nests. There’s no other way. It would be nice if it were otherwise, but the hard rain has only begin to fall over there.)

In some quarters In The Valley of Elah is going to be seen in the same light as Grace is Gone (dad-in-denial John Cusack mourning the death of his wife who was killed in Iraq), although it is much more powerful and assured.

Some might be more muted in their admiration, and they wouldn’t be wrong or right in expressing this, but I think In The Valley of Elah is an unmistakable Best Picture contender. It’s an American tragedy that every last person in this country, from whatever region or persuasion, is going to “get” deep down. Except with aberrations like Chicago, this groundwater quality is usually what gives a Best Picture nominee traction with voters.

I believe that Haggis is now a prime contender for Best Director and for Best Adapted Screenplay. Ditto Deakins for Best Cinematography and Francis for Best Editing. I can see Theron being talked up in the Best Actress category also (her role as a single-mom investigator is much less showy and grandstanding than the blue-collar character she played in North Country), and Sarandon, depending on the competition, could wind up in the Best Supporting Actress category.

Every Elah supporting player delivers a straight-up, no-fuss performance. The best are Jason Patric, James Franco, Josh Brolin, Jonathan Tucker, Frances Fisher, Rick Gonzalez, Barry Corbin, Wayne Duvall, Brent Briscoe, Mehcad Brooks, Brad William Henke and Kathy Lamkin. (Watching it is like a No Country for Old Men old-home week for Jones, Brolin, Corbin and Lamkin.)