Just a couple of guys sitting in a restaurant, talking it out. It’s not just the acting in this scene (and the fact that the actors are so legendary-iconic), but the writing. The dialogue is straight, clean…entirely about fundamentals.

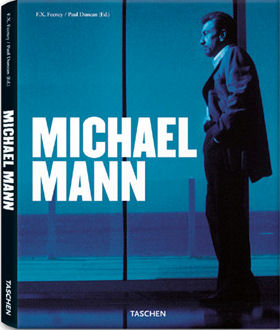

It wasn’t quite the same during a sit-down with the creator of this scene, Michael Mann, a couple of weeks ago at his office in West Los Angeles. The idea was to talk about the new Taschen book about Mann and his career — a luscious visual smorgasbord (the photos are choice in a very special off-center way) coupled with insightful, exceptionally well-sculpted analysis by F.X. Feeney . It turned out to be more of a casual chit-chat, although a fascinating one. 40, 45 minutes…the minutes just flew.

Mann just wanted to relax and talk, which meant no recording or taking pictures …cool. I didn’t take many notes as we went along; I asked about everything; there was no vein to it.

So to get myself rolling on a piece, I wrote Feeney and suggested we do an online q & a like we did before about his Roman Polanski book. So I wrote some ques- tions and he sent back the answers last night. But before I run it, consider this graph from Feeney’s first chapter:

“Over the course of the eight feature films he has directed since 1971, Michael Mann has shown himself, time and again, to be a rigorous, honest dramatist, a maker of solid worlds. So much so that in America, at least, he tends to be underrated. The most respectful of his critics define him (a bit too simply) as a realist. Certainly, Mann seeks authenticity above all…but perhaps the most accurate word for him is ‘ synthesist ‘…[an artist who] immerses himself thor- oughly, breaking the truth of a given topic down to its working parts, throwing away whatever rings false.”

I don’t just love Michael Mann’s films — I want to live in them. I want the clarity, the decisiveness, the certainty, the edge, the coolness…all of that stuff. A lot of people feel this way. Guys, mostly, but whatever. Here’s the back-and-forth…

JW: I notice Mann is actually listed as a co-author on the Taschen website.

FXF: That’s true, and fair to say. The book has three authors: I wrote the text; Paul Duncan (who also edits the entire filmmaker series for Taschen) chose the photos and directed the layouts; and Michael Mann was not only the book’s subject, he took an extremely active role in its production — providing Paul in-depth access to his archives, inviting me to witness him at work, indeed making time to sit with me for hours of in-depth interviews.

JW: How did you get that kind of cooperation from Mann? I remember you mentioning when we spoke at CineVegas that there had been a previous attempt at a Mann/Taschen book, which you were not part of.

FXF: I even mention it in the first chapter of the book, by way of dramatizing the high-pressure challenges in store for any critic who takes on a creative individual as exacting and enigmatic as Michael Mann. Beyond that, it’s not worth mentioning: Read the book! I have a strong take on Mann, which Taschen was willing to support. I had just completed the Polanski book in April 2004 when the Mann assignment came back into the open. Paul Duncan and I enjoy a good working relationship; I dove in. We were realistic and flexible. We figured that if my essay got rejected by Mann, then to hell with it…so much for a Taschen-Mann book.

But as it turned out, Mann was engaged by what I wrote. “Engaged” as opposed to flattered — near as I can tell, he’s immune to flattery; what he seems to crave instead is experience and information — and once engaged, he opened his doors to me. I spent much of the summer of Collateral (2004) in intensive conversation with him. My essay posed explicit and implicit questions he would either knock down or answer. As I hope is plain in the finished book, if there was a disagreement, we each stood our respective grounds — Michael getting the last word in most cases. I was more interested in what he had to say.

\

JW: What were the so called “high pressure challenges for any critic” who takes on Mann?

FXF: Only one — but an important one. Too many well-meaning critics and fans describe Mann as “a subverter of genres,” as a kind of movie buff hell-bent on reinvigorating the crime film. In his own view, he is anything but. “Genre” is a word for which he has no personal use.

JW: If Mann doesn’t “subvert genres,” then why are Thief, Heat, Collateral and Miami Vice all superior examples of “the crime movie”?

FXF: Because Mann sees them as pictures drawn from life. As I say, he’s interested in first-hand experience. He comes out of a tough neighborhood in Chicago, has gotten to know cops and criminals, and is himself by nature what I call “a stealth non-conformist.” By that I mean, Mann has a very self-directed, fundamentally rebellious nature, yet paradoxically he is skilled at blending in. Small wonder his heroes and villains alike so often live under-cover; Mann respects that what is least dispensible about a person’s character is that which thrives in private — in secret, even.

When other directors of his generation (Francis Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas) were establishing their flamboyant personal styles and vivid reputations through their great films of the 1970s, Mann was playing it close to the vest, working in television, a place few self-respecting auteurs would deign to spend time in those wasteland days, developing his craft as a writer-director, above all mastering the business as a producer.

By the time he made his debut feature Thief (1981), he was already full grown as an artist — and Thief is one deeply realized work, down to its tiniest fibers. Somebody once asked Mann how he exerted such control over a film’s final cut so early in his career, and he replied: “Because I cut the checks.” Amen. Or, as Crockett marvels of an adversary, early in the new Miami Vice film: “Those are skill sets.”

JW: What would you say is the personal trait that stands out above all others with Mann?

FXF: His mantra is “get it right.” By that he means, get your facts right, insure that your aesthetic decisions in making a movie follow what is actual and logical in the world at large. Mann has a strong sensual streak — music is clearly a deep (if not his deepest) source of inspiration — and a high susceptibility to visual beauty, yet he never lets his appetites for these get the upper hand. Everything in his work is subordinated to concrete use, either in terms of what interests the characters, or those dynamics which reveal the deeper character of the world to the onlooker.

Here’s one vivid example from my encounters with him. He was leafing through my Polanski book — attentive, silent, un-judging — but when he closed it, asked me one question: “What did Polanski’s father do for a living?” Damn. I had to admit, I didn’t know — Mann had stumped the band on his first try. Yet this is such a simple question, and an important one, if you think about it — “how the world works” is best revealed by the specific work people do — and I had forgotten to ask it.

JW: What did Polanski’s father do for a living?

FXF: Polanski’s father was an artist in Paris, and when he returned to Krakow in the late 1930s, it was to take an office job at a factory owned by relatives. (Thanks for asking, Michael!)

JW: Like all big-name directors, Mann has a coterie of journalist and film-critic loyalists who think he’s one of the greatest and stand up for him time and again. I am one of these, frankly. I’ve sensed for a long time now — unquestionably since Heat — a profound respect for the guy, and a kind of corresponding allegiance.

FXF: My sense is that Mann characteristically makes movies that are critic-proof — he thinks and works everything through to such a degree that few can ever seriously quarrel with his intentions or his technique. Back in the 1980s a few reviewers tried to wisecrack him into a corner over the success of Miami Vice on TV, belittling him “a glossy stylist,” and so on. I was guilty of this myself, if memory serves — but over time, the films have held up so solidly to repeated viewing that we cutups in the peanut gallery have been obliged to acknowledge, at last and belatedly, that yes, here is a giant, ingenious body of work in progress.

JW: What was the turning point for you?

FXF: The Insider (1999). Of course, I’d admired Manhunter, Last of the Mohicans and Heat as individual films — but it was watching Mann penetrate the contemporary world of corporate authority, in which matters of life and death are decided over desks and behind closed doors, that the living totality and cumulative value of his filmography became unmistakable, and a source of abiding amazement. Others felt the same way, I know.

Since that time, Mann’s only difficulties with critics have arisen out of certain specific expectations that sometimes get raised, extraneous to the intrinsic quality of the films themselves.

For example, Ali (2001) — if you grew up feeling emotionally involved with the real Muhammed Ali, or were enchanted as most critics were by the late `90s documentary about him called When We Were Kings, then accepting Will Smith in the role, or revisiting scenes from the life of Malcolm X so vividly covered in Spike Lee’s Malcolm X, became a bit of a stumbling block — at least on a first viewing. (Also, the film opened two months after 9/11, when both the viewing public and the very practice of moviegoing were heavily depressed.) See Ali now on DVD, and its overriding virtues quietly but forcefully assert themselves — Will Smith’s performance being one of them; I think it’s the best thing he has ever done.

What’s more, you have a portrait of America in the 1960s and `70s that for my money is unsurpassed in terms of its authentic detail and atmosphere. Mann intelligently, skillfully reveals Ali as a leader on a par with Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and Patrice Lamumba — a lesser filmmaker would have been content to celebrate his greatness as a boxer.

JW: How did Mann’s manner with you evolve as you got to know him?

FXF: No change. Steady, steady, steady. He knows who he is. Over time, anyone who works with him is privileged to glimpse a person of deep emotional sensitivity and compassionate awareness within the tough-guy fortress-of-solitude that is his workaday persona — he would not be able to create characters so deeply if this quality were not there — but at the same time, he is completely unsentimental. When he expresses a feeling, you trust it, even if it stings. There’s nothing willed or manipulative — no bullshit — about what he’s telling you.

JW: What do you think of The Keep…honestly? That film, to me, is the runt of the litter…almost the bizarre aberration that doesn’t belong in the family.

FXF: You ought to see it again, Jeff — as with all of Mann, it only gets better. Yet of all his films, The Keep is the only one where you sense Mann himself was unresolved about how to dramatize certain things. As I say in the book, he hadn’t yet found a way to use the audience’s imagination as an ally when dealing with monstrous evil — ergo, he shows “the monster.”

It’s interesting that one film later, in Manhunter, he successfully trusts that the Unseen is even more terrifying than what we do see. Hence, Mann removed the dragon tattoo that he originally intended to be an outward expression of torment on the skin of the serial killer, Francis Dollarhyde. “It would trivialize his struggle,” he told actor Tom Noonan. So we are forced to imagine the monstrosity inside Dollarhyde, and there it is. But The Keep is an honorable effort to achieve the same illumination.

JW: Is Mann his own singular invention, or does he stem from a tradition of distinctive realist directors?

FXF: He loves all the hardworking explorers — Kubrick, Pabst, George Stevens — but he is his own man, as an artist. Life influences him far more than other artists.

JW: The film that turned Mann on the most when he was young — the one that made him decide to be a filmmaker, was G.W. Pabst‘s Joyless Street. Which I’ve never seen. Have you?

FXF: No. And I guess this is like not knowing what Roman Polanski’s father did for a living. You’ve stumped the band, Jeff! But I’ve seen enough of Pabst’s other work (Pandora’s Box; Diary of a Lost Giorl; Threepenny Opera) to feel a lucid sense of what so excited Mann about Joyless Street at age 21 that he decided on the spot to become a filmmaker — Pabst is one who never imposes himself visibly on the story he is telling. He instead yields great power out of the characters, and his own observation of life.

JW: When Pacino asks DeNiro in Heat if he ever wanted “a regular-type life,” De Niro doesn’t say (as you relate in the book), “What is that, barbecues?” He says, “The fuck is that… barbecues and ball games?” And Pacino, almost smiling, waits a beat and a half and goes, “Yeah.”

FXF: I wasn’t quoting the line in its entirety; I was synopsizing, touching on specifics to make a larger point — and I only had 25,000 words. There are never enough!

JW: What film do you consider to be his best, and why? If you can’t name just one, try to at least give me a tie between two films.

FXF: My favorite is Last of the Mohicans — a stunning evocation of early America. Everything that is greatest about Mann — his sense of history, his love of women, his sensitivity to the intricacies of motive (even Magua the terrifying renegade has reasons for being so brutal; white men killed his wife and children); Mann’s total commitment to getting everything right, down to the least corset and chord of music. And then — selfishly — I love that period of American history. There simply haven’t been enough films about it.