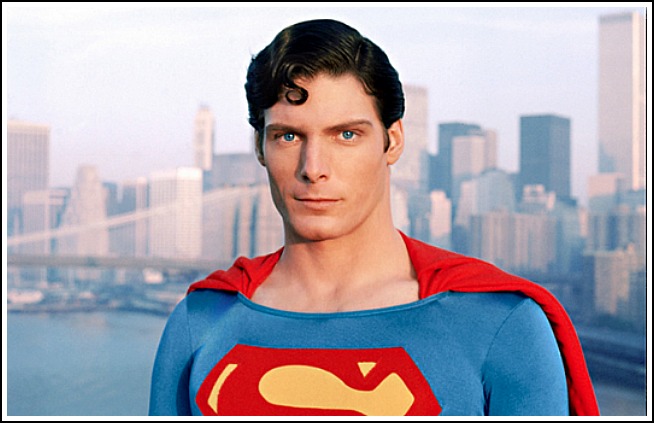

Christopher Reeve did well by critics when Richard Donner‘s Superman popped in December of ’78. This was partly due to the fact that by late ’70s standards Reeve was quite the hunk. “Reeve’s entire performance is a delight,” wrote Newsweek‘s Joe Morgenstern. “Ridiculously good-looking, with a face as sharp and strong as an ax blade, his bumbling, fumbling Clark Kent and omnipotent Superman are simply two styles of gallantry and innocence.”

What upper-echelon actors in today’s realm are ax-blade handsome in that tall, broad-shouldered, WASP-ian way? Two guys I can think of — Armie Hammer and (when he’s not summoning memories of Ernest Borgnine) Henry Cavill. But that’s about it.

Because ax-blade handsomeness isn’t trusted, much less admired. It’s even despised in certain quarters. Because it’s now synonymous with callow opportunism or to-the-manor-born arrogance. Men regarded as “too” good-looking are presumed to be tainted on some level — perhaps even in league with the one-percenters and up to no good. It’s been this way since Wall Street types and bankers began to go wild in the mid ’80s.

I was thinking this morning about how Reeve and Robin Williams were the best of friends for 30-plus years (they bonded at Juilliard in the early ’70s), and now they’re both dead. And they didn’t go peacefully into that good night either.

After his 1995 horse-riding accident, which turned him into a quadraplegic, Reeve became a kind of never-say-die spiritual hero. There’s no question that his becoming an impassioned stem-cell-research advocate left a more profound impression on the world than his performances ever did. But he was a fine, appealing actor.

Reeve had a ten-year run (’78 to ’88) as a marquee name. Superman launched him; Switching Channels finished him off. His best film performances were in Jeannot Szwarc’s Somewhere in Time (’80), Sidney Lumet’s Deathtrap (’82) and James Ivory’s The Bostonians.

His best performance ever was in the Broadway stage production of Lanford Wilson’s The Fifth of July, in which he played a gay paraplegic Vietnam veteran. It ran in the late summer or fall of 1980. Jeff Daniels and Swoozie Kurtz co-starred.

I had an experience with Reeve in late ’80, when I was a pup journalist living in New York. It began with an interview piece I wrote about him for a New Jersey weekly called The Aquarian, the main subject being Somewhere in Time.

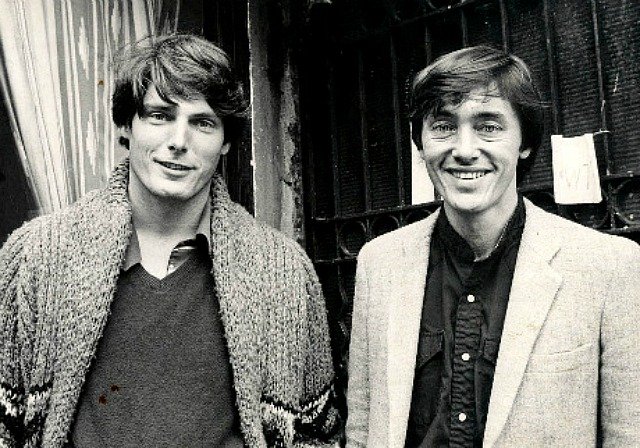

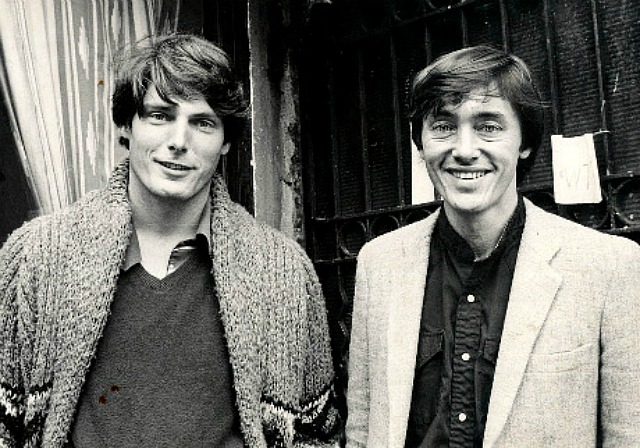

Reeve and I met for the interview at a restaurant on upper Columbus Avenue. I had done my homework and prepared a lot of deep-focus questions, and I think he enjoyed our talk. Sonia Moskowitz, a gifted photographer whom I went out with a year or so later, sat in for the interview and then took some photos of Reeve (plus one of him and me) outside the restaurant. Then we went back inside to sort out the bill.

I was a bit green back then, but I’d done a few celebrity interviews and knew that the basic rule was that the studio always picked up the tab. I assumed this would be the case but there was no Universal publicist at the restaurant to cover the check, and I didn’t know what to do because my Aquarian editor had never talked to me about expenses, and I didn’t have the cash to cover it on my own.

I thought Reeve (wealthy actor, right?) might step up to the plate and get his money back from Universal. It was that or somebody would have to leave a personal check or wash dishes. Talk about embarrassing. When I told Reeve I was a bit light I could see he was irritated. We kind of hemmed and hawed about it on the sidewalk, I offered everything I had (about $15 bucks), and he finally dug out his wallet and said, “Well, all right” and paid the balance.

When I wrote my piece I threw in a couple of graphs at the end about this bill-paying snafu. I thought it was both amusing and humanizing on some level that a successful big-name actor who’d played Superman was capable of getting flustered about paying a check, just like anyone else.

A week or two later, just as the Aquarian piece came out, I went with a couple of friends to see Reeve in The Fifth of July. We visited his dressing room to say hello after the show, and as an ice-breaker I asked if he’d seen the article. Wrong question. Reeve hadn’t liked my closer and said so. He was scowling at me. I felt like I was suddenly in the Twilight Zone. I thought I’d written about the restaurant-tab thing with humor and affection. I’d figured this plus the fact that the overall piece was highly flattering would have charmed him.

To soothe things over I wrote him a note the next day saying I was sorry he had that reaction, that I really thought the humor I got out of our check-paying episode made it a warmer, fuller piece, and that I hoped he wouldn’t hold a grudge.

A few weeks later I ran into Reeve at an invitational party at a Studio 54-like roller skating joint in Chelsea. As soon as he spotted me he came right over, smiling, and said, ‘Hey, Jeff. Got your note…everything’s cool..don’t worry about it.” We shook hands, he smiled again and said “peace,” and that was that.

What this told me about Reeve is that he could be thin-skinned, but was also capable of being gracious. It also told me that deep down he was into dignity and protocol and doing things a certain way. I think that attitude bled into his acting on a certain level, and that’s why he wasn’t quite Marlon Brando.

I’ve lost or can’t find my first-generation copy of the original print of this. The shot was taken in the early fall of 1980. I’ve asked photographer Sonia Moskowitz if she has the original neg or at least a decent print that she could maybe scan and send along.