N.Y. Times critic A.O. Scott has delivered one of his perfect little sonnet pieces on James Foley and David Mamet‘s Glengarry Glen Ross (1992). Except he doesn’t mention Foley. No one who talks about this film ever does. Because GGR is a show about one thing and one thing only — Mamet’s “hard-boiled, lyrical mysticism,” as Scott puts it.

Except it’s not, as Scott infers, a commentary on the “the current economic crisis [that] had its origins in the real-estate bubble and bond market frenzy of the last decade.” Nor is it an essential expression of the Clinton-changeover ethos of 1992, when the film was released. Glengarry Glen Ross is based on Mamet’s real-estate job in the late ’60s but it became what it became because it understood and reflected the emerging greed and malice of the Ronald Reagan era — when the seed of everything that stinks today was sewn, in the view of Paul Krugman — and that is when the play’s vitality was greatest, when it gleamed and instructed like a demon orator.

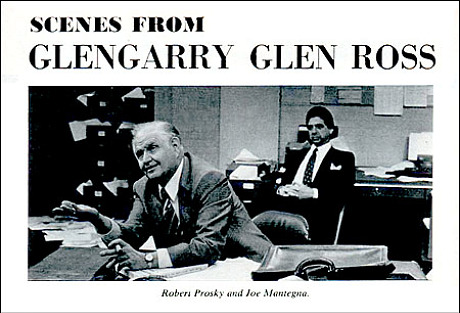

I saw Gregory Mosher’s original New York production just before opening night — some time in mid-March of 1984 — with N.Y. Times theatre critic Frank Rich sitting a few aisles away, and with a truly electric snapping-turtle cast — Joe Mantegna, Mike Nussbaum, Robert Prosky, Lane Smith, James Tolkan, Jack Wallace and J. T. Walsh. And I am telling you that night was it — the Glengarry Glen Ross apogee.

Foley’s film improved upon Mamet’s stage play by way of Alec Baldwin‘s live-reptile speech to the salesmen (“Third prize is you’re fired”) and Kevin Spacey‘s performance as the office manager (i.e., Walsh’s part), but was otherwise only so-so. In my head I’ve always blamed this on the influence of producer Jerry Tokofsky, whom I’ve always heard was a bit of a cowardly lowballing weasel, but I wasn’t there so what do I really know? Nothing.

The movie took too long to get funded and so, as noted, it came out too late — it missed the cultural synchronicity. And Foley smothered it in standard-issue noir atmosphere — darkness, neon, constant rainstorms — and in so doing blew off the unfettered, straight-from-the-shoulder, granite-like clarity of the play. And Jack Lemmon overdid the jittery desperation of the sweaty downswirling salesman known as Shelley “the machine” Levene. (For my money Robert Prosky did him better on-stage — anxious and vulnerable but also snarly, pugnacious, testy.)

Worst of all the film doesn’t have Joe Mantegna as Ricky Roma — a role that Mantegna owned like Humphrey Bogart owned Duke Mantee in The Petrified Forest and Jason Robards owned Murray Burns in A Thousand Clowns. Al Pacino does very well with the part — his handling of the big existential pitch speech that closes Act One is effectively phrased — and we all understand that movie stars like Pacino routinely take parts away from guys like Mantegna for the most sensible of reasons, but it was still wrong.

To my knowledge Mantegna’s Roma was never captured on film or tape (even audio tape), and for this history does not look kindly, especially upon Jerry Tokofsky.

Robert Prosky, Joe Mantegna in Gregory Mosher’s original 1984 stage play of Glengarry Glen Ross