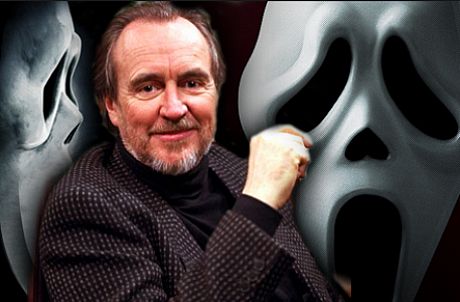

One of the coolest things about the late Wes Craven, who passed earlier today from brain cancer, was the way his name sounded like a low-rent villain in a drive-in movie. The sound of it spoke to the slimier, spookier regions of the human soul — craven being synonymous with “cowardly, lily-livered, faint-hearted, chicken-hearted, spineless, pusillanimous” and rhyming of course, with Edgar Allen Poe‘s “The Raven.” Nothing good could come of such a name or a man using it, you might have thought, and yet Craven became a major horror-exploitation figure in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s and wore the crown of being the most influential fright maestro in Hollywood’s second-tier realm.

Craven’s career highlights included The Last House on the Left (which Roger Ebert described when it opened in 1972 as “a tough, bitter little sleeper of a movie that’s about four times as good as you’d expect”), The Hills Have Eyes (’77), the original Nightmare on Elm Street (’84) and the whole unfortunate Scream franchise of the mid ’90s and beyond, which made Craven very rich.

Craven also directed Vampire in Brooklyn, The Serpent and the Rainbow, The People Under the Stairs, Cursed, Red Eye and My Soul to Take.

How did Craven manage to direct Music of the Heart, a 1999 Meryl Streep film of Roberta Guaspari, co-founder of the Opus 118 Harlem School of Music? Politically, I mean. How did he swing it? That was always a curiosity.

Craven and Bruce Wagner co-wrote A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors, which was passable in my book. I barely remember it, to be honest.

In ’85 I served as unit publicist on the second Freddy Krueger film, A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Fredddy’s Revenge, so don’t tell me. True, it wasn’t nearly as scary as Craven’s original and it was directed by Jack Sholder (who, let’s not forget, directed the drop-dead-brilliant The Hidden two years later) and not Craven, but I was there, I put in the hours, I absorbed the Craven after-aroma and I therefore possess a certain nostalgic authority, at least as far as the New Line Cinema psychology was concerned in those days.

Oh, yeah — there was also Craven’s New Nightmare (’94), which was actually pretty good and was nominated for best feature at the 1995 Spirit Awards. Let it be known that I wrote a mediocre screenplay in ’86 or thereabouts called Freddy Goes to Hollywood, which was about Freddy Krueger crossing over into reality and making life miserable for a crew making a Freddy Krueger film. This was also more or less what New Nightmare was about. I submitted my screenplay to New Line, and it was appropriately rejected. It wasn’t awful — a clever idea — but I wasn’t born to screenwriting.

“I come from a blue-collar family, and I’m just glad for the work,” Craven said in an interview with writer-director Mick Garris last year.

“I think it is an extraordinary opportunity and gift to be able to make films in general, and to have done it for almost 40 years now is remarkable.

“If I have to do the rest of the films in the (horror) genre, no problem. If I’m going to be a caged bird, I’ll sing the best song I can.

“I can see that I give my audience something. I can see it in their eyes, and they say thank you a lot. You realize you are doing something that means something to people. So shut up and get back to work.”