The mark of any exceptional film is the won’t-go-away factor — a film that doesn’t just linger in your head but seems to throb and dance around inside it, gaining a little more every time you re-reflect. This is very much the case with Anton Corbijn‘s Control, the black-and-white biopic of doomed Joy Division singer Ian Curtis.

I finally saw Control at a market screening last Wednesday night (5.23) at the Star cineplex, and it’s definitely one of the four or five best flicks I saw at Cannes — a quiet, somber, immensely authentic-seeming portrayal of a gloomy poet-performer whom I didn’t personally relate to at all, but whose story I found affecting anyway.

Corbijn, a music-video guy, was obviously the maestro, but a significant reason why so much of Control works is newcomer Sam Riley, who portrays Curtis as a guy who was unable to throw off that melancholy weight-of-the-world consciousness that heavy-cat artists always seem to be grappling with. There is no such thing as a gifted writer/painter/poet/sculptor/filmmaker who laughs for the sake of laughing and does a lot of shoulder-shrugging. Everything is personal, and everything hurts deep down. And Riley makes you feel what it’s like to be a guy who just can’t snap out of it.

This plus the ’70s northern-England atmosphere and Martin Ruhe‘s utterly fantastic black-and-white photography combine in a perfect slam-dunk that amounts to perhaps the finest rock-music biopic dramas I’ve ever seen. How many really good ones have there been? My mind is a blank.

Curtis, the movie says, was a mopey epileptic who couldn’t live with the fact that he’d made a mistake in marrying a domestic mouse named Deborah (Samantha Morton), whose book about Curtis, “Touching From A Distance”, was the basis of Matt Greenhalgh‘s screenplay. Curtis especially couldn’t handle the stress and guilt of an ongoing extamarital affair with a Belgian journalist named Annik (Alexandra Maria Lara).

The guy never heard of double-tracking? Of cutting marital ties but at the same time staying close with your ex-wife and supporting the child you’ve had with her? I don’t see the problem, but this plus the epilepsy sent Curtis over the edge and he wound up hanging himself at age 23.

Before last Wednesday, I had listened to Joy Division tracks maybe five or six times. (Not counting what I heard in 24 Hour Party People.) Now I’m suddenly into them, and am definitely planning on buying one or more of their CDs the next time I’m at Amoeba.

Acquiring the North American rights to this quietly jolting biopic may turn out to be the best thing Harvey Weinstein did during his stay in Cannes…unless he paid too much.

The first word that came my way after the Directors’ Fortnight debut screening a week ago Thursday was “routine,” “overhyped,” “fairly conventional,” “too domestic” and so on. The person who passed most of this along to me is an exceptionally alert critic who obviously has a right to his opinions, but he gave me a bum steer, dammit.

Here’s a Control clip that’ll give you a little taste. Here’s another source for the same clip.

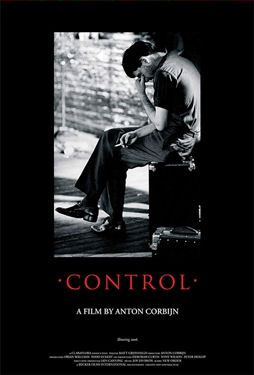

Control star Sam Riley (l.), director Anton Corbijn

The stark black-and-white photography is more than merely attractive. It feels like a fit with the somewhat gloomy aesthetic of the punk and post-punk era, and Joy Division’s music in particular. I can’t stop feeling depressed over the fact that we’re all doomed because life is always assaulting us and pulling us down and giving us pain, etc.

Tony Kebbell‘s portrayal of Joy Division manager Rob Gretton — a nervy, mouthy hammerhead sort, is easily the second best performance in the film. He’s also the sole dispenser of comic relief.

I was suspicious of Control early on due to Greenhalgh’s script being based on Curtis’s book (ex-wives and in-laws are generally the least honest and most sentimental sources when it comes to reconstituting an artist’s life and work), but the film doesn’t feel the least bit sanitized or soft-peddled.

I particularly liked that there’s nothing showy about Control — no big emotional blow-ups or Oscar-bait depictions of agonized primal screams. The opposite, really. There’s a great dark moment when Curtis predicts in a quiet, matter-of-fact manner that his young daughter Natalie will probably hate him when she gets older. (Because he barely pays attention to her.) His wife is staggered that he would say this and says he’s delusional. But Curtis knows what he knows and reiterates that “she will…she will.”

Some guys are born poets and songwriters, and some guys should always wear condoms when sleeping with the girl next door.