Here’s another In The Valley of Elah rave, written by the New Yorker‘s David Denby, that all the Haggis haters and Elah dissers need to gang up on and dismiss before it has any influence upon anyone who might be half-persuaded this could be a film of true merit.

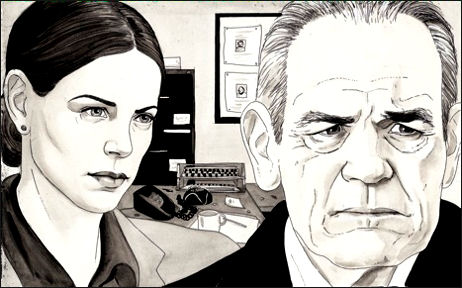

Charlize Theron, Tommy Lee Jones (illustration by Lara Tomlin)

C’mon, guys, you know the drill….piss away. But one thing you can’t piss on, and that’s the fact that Denby knows how to write. Read this piece and tell me it doesn’t arouse your taste buds, even if you’ve seen Elah. (I’ve seen it three times and it made me want to go back again.)

Warner Independent would be well-advised to turn the entire review into a big cardboard standee and put it in theatre lobbies everywhere.

Denby’s riff on Elah star Tommy Lee Jones is the best part: “In his long movie career, Jones has never wasted a word or an emotion. When he’s silent, his glinting eyes and suppressed smile suggest a secret held in reserve. When he speaks, at Gatling-gun speed, the words come out as definitive. There’s no arguing with this man; he doesn’t give you an opening. He says only what he wants to say, and he delivers his lines with commanding off-kilter intonations (rising when you would expect falling, or just deadpan).

“Jones is the driest and most thoroughly stylized of American movie stars — a natural-born hipster wit — but he’s not a lightweight. Even in a spoof like Men in Black, his ease and quickness carried authority (and he didn’t let the grinning Will Smith ace him out).

“In Paul Haggis‘s In the Valley of Elah, Jones plays a Vietnam vet and former M.P., Hank Deerfield, whose son, Mike, after serving in Iraq, has gone AWOL in America. Jones has portrayed military men before, but Hank Deerfield is the role of a lifetime, and he has stripped himself of any vestige of vanity to play it.

“The vertical lines in his face run deeper than ever; a ten-dollar haircut exposes his big ears. Suddenly, he’s a primal American image — awkwardly iconic, with a creased-leather face from a Depression photograph — and he gives a great, selfless, and heartbreaking performance that completely dominates this elusive but powerful movie.

“Haggis, the writer-director of Crash, has done something shrewd: he has mounted a devastating critique of the Iraq war by indirection. Rather than dramatizing, say, the disillusion of a young soldier as he experiences the chaos of the occupation, he has moved disillusion into the soul of a military father. And the anguish that the father feels is all the more affecting because it’s held in check by Jones’s natural reticence.”