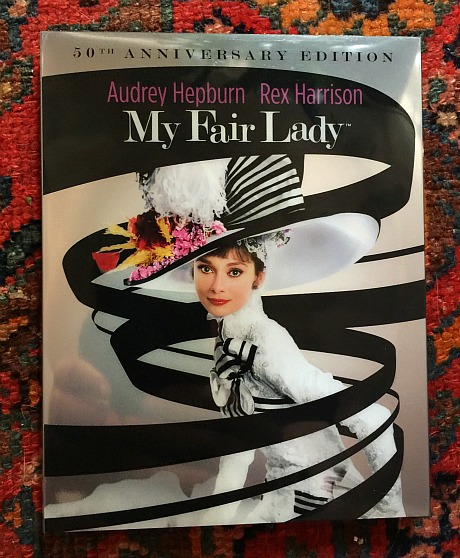

Yesterday I watched portions of the 50th anniversary Bluray of George Cukor‘s My Fair Lady (’64), and more particularly Robert Harris‘s 8K digital restoration of this multi-Oscar-winning film. And then I went to Westwood’s IPIC theatre to catch it on a 30-foot screen.

Say what you will about My Fair Lady itself, but the images are as good and clean and flush as they’ve ever looked, and probably better. I can’t say enough about the lusciousness of the compositions, about the value of this kind of exacting work — a blue-chip rebirth or recreation of the highest order. The last My Fair Lady Bluray, released in 2011, delivered less than 30% of the resolution contained in the original Super Panavision 70 photography, but Harris has brought this 51-year-old film back. Hats off to him and the Paramount folks who signed off on it.

Now that I’ve congratulated Harris on a job well done, I’m free to say that I truly can’t stand this leaden adaptation of Lerner & Loewe’s legendary musical, which debuted on the Broadway stage in 1956. It’s based, of course, on George Bernard Shaw‘s Pygmalion, a non-musical first produced on the London stage in 1913.

At various stages along the way and perhaps as late as the initial Broadway version, Pygmalion/My Fair Lady delivered, I’m sure, a semblance of real life and authenticity, but in the hands of Cukor and particularly Jack L. Warner, who personally produced the film, My Fair Lady was turned into a pageant — a slow-moving, exactingly designed thing that suppressed or suffocated whatever appealing elements were presumably there 59 or 102 years ago.

It’s lumbering and lifeless — an odd hybrid of a stage musical that’s been heavily starched and weighted down + an early 1900s fashion show + a tableau of cinematic stodginess. It’s in love with its own lavish budget and dedicated to making everything look and feel as sterilized as possible. There are horses left and right in the Covent Garden scenes, and the cobble-stoned streets are always whistle-clean without even a lump or two of horseshit.

My Fair Lady delivers a fake atmosphere, a sound-stage imitation of life as it was in early 20th Century London, and I hated every minute of it except for Rex Harrison‘s performance as Henry Higgins. And yet it pains me that he won the Best Actor Oscar for it — I would have given the award to Becket‘s Peter O’Toole.

Audrey Hepburn‘s acting as Eliza Doolittle is chalk on a blackboard. Her Cockney accent feels oppressively learned — exactly the style of speech that a skilled actress would deliver under the tutelage of an expert voice coach. Every second of her performance is theatrically painful — she shrieks and howls (“Owwwww!”) and “acts” like she’s playing to the rafters. Somehow or some way, Julie Andrews (who originated the role in ’56) would have been much better.

Whenever the extras are strolling around on the Covent Garden or Ascot sets it’s like watching a company of well-dressed mummies or mannequins pretend to be human. I wanted to see their throats slashed by an army of zombies.

Warner, a huge control freak, was apparently on-set most of the time, tinkering around and probably telling Cukor what to do. The film reflects Warner’s aspirations and values — upper-crust society folk are the luckiest and happiest, money is very calming and good for the soul, and there’s nothing so delectable as ultra-glossy, spare-no-cost costumes and lavish sets and a general sense of affluence permeating every last nook and corner.

At every step it feels as if Harry Stradling‘s Super Panavision 70 camera weighs ten tons. You sit there and watch it and you can feel the rigor mortis settling into your bones.