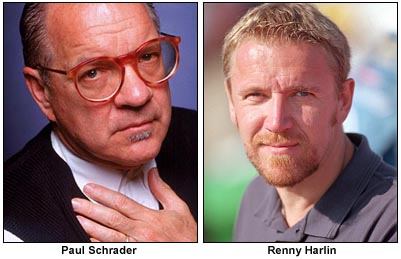

Face-Off

On Tuesday afternon I saw a DVD of Paul Schrader’s Exorcist prequel flick, which has been titled as Dominion: A Prequel to The Exorcist. Warner Bros. will release it on May 20, and it’s about friggin’ time.

Do I have to recount the whole Exorcist mishegoss over the last two or three years? Are there people who haven’t read about Morgan Creek’s James Robinson shelving the Schrader because he felt it wasn’t scary or pea-soupy enough, and then hiring Renny Harlin to shoot a slicker, aimed-at-the-youth-market version, blah blah?

Stellan Skarsgard (r.), star of Dominion: A Prequel to The Exorcist, and costar Billy Crawford (l.) in burning demonic possession mode.

The story of the Schrader version, which was shot between late ’02 and early ’03, coming back from the dead and finding release is in this week’s Entertainment Weekly , in a “News and Notes” article by Missy Schwartz.

What I have to say may not muss your hair and knock you out of your chair, but it’s the truth. Schrader’s version is the better film.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

By that I mean smarter and more grounded and being actually about something. It’s one of Schrader’s most thematically satisfying films, and there’s a caring and compassionate tone in the third act that feels unusual coming from the writer of Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Hardcore and American Gigolo.

Okay, it has a couple of lumpy elements (one or two CG shots that don’t quite cut it, a lead female performance by Clara Bellar that feels stiff and awkward), but nothing to throw you off the rails.

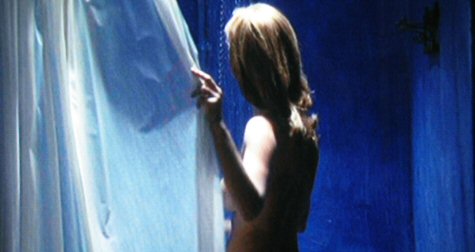

The Schrader isn’t as juiced as the Harlin and it doesn’t have Izabella Scorupco (who has, for me, a close-to-breathtaking shower scene in the latter), but the Schrader is so much fuller and richer and more rooted than the Harlin it’s not even funny. It’s an actual movie, as opposed to a thrill-ride reel.

And the star of both films, Stellan Skarsgard, delivers a tenderer, more expressive performance in the Schrader version. His acting actually left me feeling emotional allegiance and admiration for a Catholic priest character, which I frankly haven’t gotten from any theatre-viewed film since…well, William Friedkin’s The Exorcist .

When I see a priest in a movie, I usually think “pederast alert!” or “okay, here comes the obligatory guy-who-doesn’t-get-it” or something along these lines. Schrader’s film manages to punch through all this and come up with a real hero in Skarsgard’s Lankaster Merrin, a Dutch priest who will eventually grow old and turn into Max von Sydow and meet up with Linda Blair and die of a heart attack in her refrigerated bedroom.

I saw the Schrader after watching Harlin’s Exorcist The Beginning, which came out last August and hit the DVD shelves on 3.1.05. I never bothered to see the Harlin, and I probably wouldn’t have even rented it on DVD if it hadn’t been for the arrival of the Schrader.

I have to say that I half-liked the Harlin…at first. Because it’s so beautifully photographed (by the great Vittorio Storaro, who also shot the Schrader version) and because it has that expensive texture and accelerated rhythm and feeling of sublime polish that big-budget films always have because people are somehow comforted by them (as I was myself, to a limited extent).

But it gradually gets worse and worse (i.e., stupider, tackier, more desperate) and by the time it’s over it’s hard not to hate it.

The Harlin is a better cheap-high movie than the Schrader, granted, but in what kind of perverse universe do we applaud cheap highs?

If you go to the Schrader saying, “Okay, I want to see some really cool stuff I can talk about with my friends later on,” you may be disappointed. In fact, I was a tiny bit disappointed…at first. But it gets better and better, and by the time it’s in the home stretch it’s paying off on a fairly profound level.

There are loads of similarities between the two films, and a few key differences.

The Schrader takes place in 1947. The Harlin happens in 1949. Don’t ask why. Even Schrader, whom I spoke to this morning, says he doesn’t have a clue.

Both films are about how Merrin re-connects with his belief in God and the righteous scheme of things after losing faith in just about everything after enduring a horrible Sophie’s Choice-like incident during World War II.

A German officer (played by the same actor in both films) is threatening to kill a large group of Dutch villagers if someone doesn’t confess to killing of a German soldier. He orders Merrin, the local Catholic priest, to select the guilty party…only one person at first, and then, after Merrin initially refuses, ten.

Schrader’s film begins with this episode, and is much more psychologically intriguing (by the virtue of being better written) than it is in the Harlin film, which flashes back to this episode in piecemeal fashion.

The Harlin film is totally shameless in having the German officer shoot an innocent little girl in the head. The Schrader isn’t any less traumatic than Harlin’s version, but it doesn’t feel like it’s exploiting a terrible situation.

Establishing title card in the Harlin version…

..and in the Schrader film.

The main story line of both films is about Merrin facing fundamental evil during an archeological dig in Kenya, where an ancient cathedral is being excavated…along with some long-buried demonic forces.

This unholy emergence not only forces Merrin to eventually confront a living devil, but to rediscover his lost faith…mainly, obviously, because it’s the only weapon that will work.

The Schrader is much more layered and ambivalent in some ways about the way native Africans regard the emissaries of Christianity. Some characters feel that Christianity is a bringer of a kind of plague. There is one male character, embittered about losing his son, who picks up a framed painting of Jesus Christ at one point and smashes it on a desk and then throws it to the ground.

And yet the conclusion of Schrader’s film is one of the most spiritually centered I’ve ever seen. Skarsgard’s Merrin is standing tall and firm and fully resolved about who he is and what he needs to do as a priest in order to fight evil. Merrin is also a priest again at the end of Harlin’s film, but the undercurrent isn’t as strong.

There’s a female doctor in the Schrader film played by Pellar. The doctor in the Harlin version is played by Scorupco, perhaps not in a fully believable way (female doctors are rarely this attractive, in my experience) but she’s still a better actress that Pellar. And her slightly-older-fashion-model, eastern-European quality (she’s Polish-born) is highly stimulating.

The great Izabella Scorupco in Harlin’s Exorcist: The Beginning

Scorupco’s breasts are (or should be) objects of sincere religious worship. They require abasement and groveling on the church floor. They made me feel born again, or do I mean newly born? Harlin deserves full credit for getting her shower scene just right.

Gabriel Mann plays a young and ardent Catholic priest in the Schrader version, but he is replaced by a somewhat less passionate, altogether less reliable priest, played by James D’Arcy in the Harlin.

There’s a local native guy named Chuma (played by Andrew French in both) who is Merrin’s closest and frankest ally. He seems more of a typical secondary character in the Harlin film, and a more intriguing and layered fellow in the Schrader version.

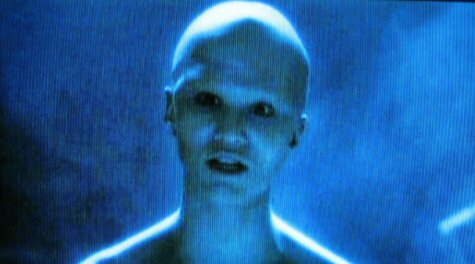

The Harlin film has a young African boy of about nine or ten falling victim to demonic possession. The possession host in the Schrader is a 20-something character named Cheche, played by pop star Billy Crawford. Sickly and spindly at first, his demonic inhabiting doesn’t turn him into a Linda Blair-type monster but an androgynous-like Hindu God figure with his physical maladies gone and his personality warped by ego, ferocity and manipulation.

Painting of Satan as it appears on buried cathedral walls in Harlin’s version.

Billy Crawford in Satan mode in Schrader’s film.

This is far, far more interesting than the usual possessed by Beelzebub or the demon Pazuzu or Izusu crap in the Harlin version.

On the DVD I saw, the Schrader version looks like it was shot in 1.85 (i.e., standard Academy ratio) and the Harlin version is clearly framed in 2.35 to 1.

Schrader said that his version was actually shot in Univision, a system devised by Stroraro which has a wider aspect ratio than 1.85, and will be projected in theatres as Scope.

Schrader’s is more political than Harlin’s in the character of some British troops. They are portrayed as seriously belligerent pissers in his version but they barely figure in the Harlin film, except for the suicide of a certain officer character. (He shoots himself in the mouth in both films.)

Skarsgard seems to weigh a bit more in the Schrader version. He might be ten or fifteen pounds lighter in the Harlin film. His hair might be a touch blonder and he even seems a bit tanner.

Slightly fuller-faced Sarsgard as he appears in Schrader’s film…

..and as he appears in Harlin’s.

The pacing of the Schrader film has been slowed down. “I wanted to make it feel like an older film,” Schrader told me, “rather than follow the typical pace of another jacked-up, pumped-up horror film.”

Schrader was contractually obliged to keep his yap shut last year before the Harlin film opened, but the gloves are off now.

“I saw in the Harlin film every bad idea that I had fought off,” Schrader told me. “Every bad Jim Robinson idea that I rejected, re-surfaced in the Harlin film, so I think the issue of true authorship is pretty clear.”

Schrader’s film cost about $30 million; the Harlin cost another $50 million. The total domestic gross for the Harlin as of last November was about $42 million. I don’t know what it’s made worldwide and on DVD, but probably another $50 or $60 million, at least, and maybe a lot more.

Would the Schrader film have earned as much? I doubt it. It’s not a mass-audience film. But when it’s over, you know you’ve had some nutrition. The Harlin makes you feel like you’ve just wolfed down a Big Mac and some fries.

Dutch villager-killing German officer as he appears in Schrader’s film…

…and as he appears in Harlin’s version.

And of course, people like junk food. They know Big Macs are mostly chemicals and ground-up noses and ears and hooves and fatty sauces and most people don’t care. They just want the rush, and guys like James Robinson knows this.

By all means see the Schrader when it opens, but the more interesting thing to do is to watch these Exorcists prequels in tandem on DVD, like I did yesterday. Robinson and Warner Bros. should have put them both out simultaneously in theatres, a plan I suggested in this column on 8.11.04.

I quoted film critic and essayist David Thomson in that particular column. At one point he attempted a reading of why Schrader, who has never been and never will be a horror film kind of guy, took the deal to make the Exorcist prequel in the first place.

“There had to be an understanding on Paul’s point of view what a troubled route he was taking,” Thomson said. “He must have known what problems he was in, and I guess he took a gamble that they would argue it and change it a bit, and then let it go. I assumed he had made a bargain with himself that he could do [this film] to please himself and Morgan Creek at the same time.

Billy Crawford in third-act scene from Schrader’s Dominion.

“I don’t know why they hired him,” Thomson continued. “It must have been clear in the script there were not great torrents of vomit.” Thomson saw a version of Schrader’s cut early on, and said in the piece that it “didn’t really seem like a continuation of the Exorcist franchise, and to that extent one could foresee trouble. Schrader had made a film about spiritual isolation…a study in a crisis of faith.”

Except it’s not a troubling experience to watch. Okay, the first part is, a tiny bit, but you get past that soon enough, and then it gathers force and it ends like gangbusters.

Schrader’s film may not work for your 15 year-old son or nephew, but unlike 97% of the horror films cranked out these days, it has an actual undercurrent. It’s a film about a spiritual tug-of-war by a guy who has written and directed more films about spiritual (and often volatile) conflict than anyone else I can think of.

If you don’t believe me or you’re not sure, click on Schrader’s IMDB page and read his credits.

Design for Flying

We’ve all seen that Man of Steel get-up that Brandon Routh will be wearing in Bryan Singer’s currently-rolling Superman Returns (Warner Bros., 6.30.06). And Movie City News recently ran a photo created by some fanboy site with a more routinely designed outfit, which is obviously meant as a suggestion.

The message, which I sense is probably endorsed by a good number of those who are jazzed about the Superman mystique and are looking forward to the film, is that Singer not do to Superman what Joel Schumacher did to Batman with the ass closeups and those pointy nipples on the chest plate.

The Singer suit uses burgundy instead of traditional fire-engine red for the shorts, cape and boots, and has Routh wearing hot go-go dancer bikini briefs instead of the standard gym shorts that Chris Reeve used to tool around in.

The fanboy designer, whomever he or she is, will eventually learn to live with the burgundy, but he/she obviously doesn’t like that bikini shit. The alternate design is pure D.C. Comics and straight out of the 1930s (or 1950s, a la George Reeve). The fanboys can see what’s going down and…well, draw your own inferences.

Of course, the boat has sailed and whatever kind of Superman Routh is going to be (and whatever his suit may end up conveying), it’s a done deal and the fanboys will have to make their calls as they see ’em.

Singer gave the X-men movies a certain dimension, I think, by subtly portraying the sense of social apartness that mutants feel in terms that any socially aware gay guy could relate to. I’m not saying this was overt, but it was there.

Remember that hilarious Roger Avary riff that Quentin Tarantino acted in Sleep With Me about the subtext of Tom Cruise’s Maverick character in Top Gun? “Go the gay way, go the gay way…you can ride my tail,” etc.?

I used this to mess with Jerry Bruckheimer and the late Don Simpson during a Crimson Tide junket interview about ten years ago. I told them, “Guys, you’re missing out on a whole marketing angle here. You should do an Advocate cover story and talk about the gay subtext in all your films, starting with the submarine in Crimson Tide.”

Monster Talk

“Your source wasn’t lying about Monster-in-Law being a hit waiting to happen.

“Unless the anti-Lopez sentiment keeps the crowds away, it should be a hit. I saw it this morning, and the audience went nuts for Jane Fonda’s wonderfully whacked-out performance as Viola Fields, a Barbara Walters type who loses her grip when she’s replaced on her talk show, ‘Personal Intimacy,’ by a ditzy hottie.

“The movie seemed to strike an especially strong chord with women who might have endured similar situations in their own lives.

“Still reeling from her abrupt fall from grace, Viola freaks when her son, a doctor (Michael Vartan, whose role is so perfunctory we never really even learn what his specialty is), proposes to Charlie (Lopez), a dogwalker/yoga instructor/aspiring designer, who also works as a temp in a doctor’s office.

“Viola throws the couple an engagement party and invites numerous celebrities and diplomats, just so she can introduce her future daughter-in-law with ‘this is Charlie — she’s a temp!’

“For those in the audience who have fantasized about seeing J.Lo humiliated, insulted and hassled, most of the rest of the film is going to be a delight. Wanda Sykes also got more than a few laughs as Viola’s put-upon assistant, who is caught in the crossfire between Viola and Charlie.

“Monster-in-Law is not a comedy classic, but it’s good fun and an excellent reminder of how sharp and funny Fonda can be.” — James Sanford.