Documentarian Bob Smeaton has done well by himself and his subject, the late Jimi Hendrix, in Jimi Hendrix: Hear My Train A’Comin’ (PBS, 11.5). He’s delivered a stirring, well-crafted valentine — a two-hour portrait of a much-worshipped, gentle-mannered, extremely modest genius who loved the ladies and was obsessively devoted to playing guitar. Which is all true as far as it goes. But this is a project controlled by the Hendrix family (i.e., Experience Hendrix, LLC), and if you know anything about this notoriously conservative-minded bunch you know what that means. Almost all the details about Jimi Hendrix’s short life that allude to any kind of subterranean undertow or inclination (such as the ingestion of psychedelic drugs) have been pretty much scrubbed out.

Lingering observation #1 is that Jimi was shy and insecure off-stage but became a whole ‘nother manifestation on-stage — he transformed into some kind of sexual dynamo and cosmic sorcerer. L.O. #2 is that Hendrix never put the guitar down…not once, not ever. (How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice.) L.O. #3 is that he seduced a lot of women.

The film does a good workmanlike job of laying down the facts of his first 24 years, before he made it. The early days of playing on the Chitlin circuit, and then for James Brown and the Isley Brothers. His father, uncle, sister and friends all reminisce. The uncle says he was clearly talented from the get-go, that he could pick up songs as a kid without reading the music. But once things start happening for Hendrix in late 1966, which is when he went to England with manager Chas Chandler, the doc starts avoiding this and that.

The biggest avoidance is the psychedelic spiritual ecstasy stuff. The doc acknowledges that Hendrix dropped acid, initially with Linda Keith in New York City in late ’66, but it ignores the whole spiritual-satori aspect of his life — the cosmic-mystical flotation side which led to all those God-touching songs on his first three albums (Are You Experienced?, Axis Bold As Love, Electric Ladyland). To hear it from Smeaton & Co. Hendrix simply came along at the right time and picked up on the psychedelic rock stylings of the mid ’60s and blended it with his expertise at blues and soul (which he did, of course) as a way to make it big. The doc ignores that Hendrix was a full-on participant and psychedelic traveller in those days, that he was dropping and going “in there” and creating rock poems out of those transcendent visitations. Blowing this off is like telling the story of Braveheart‘s William Wallace without mentioning his belief in Scotland’s independence from England.

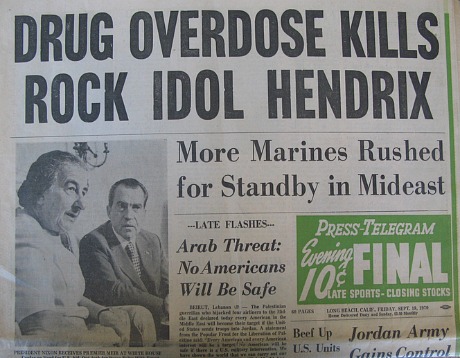

The doc also skims over the particulars of his death on September 18, 1970, at the age of 27. It says his girlfriend of the moment, Monika Danneman, gave him some sleeping pills that were stronger than he realized and that he took too many. In fact the recommended dosage was 1/2 to a single tablet and he took eight of them — between eight and sixteen times more than he should have. He also had a fair amount of wine in his system, which may have been a factor in his sloppy pill intake. The doc also ignores that he drowned in his own vomit. It wasn’t pretty. A tree didn’t fall on him. Hendrix didn’t die nobly by trying to save a little girl from drowning in Hyde Park. He took himself out with a thoughtless and stupid act.

Smeaton also ignores that Hendrix might have had some side issues with alcohol. Steven Roby and Brad Schreiber‘s “Becoming Jimi Hendrix: From Southern Crossroads to Psychedelic London, the Untold Story of a Musical Genius” and Charles Cross‘s “Room Full of Mirrors: A Biography of Jimi Hendrix” reported that Hendrix was sometimes angry and violent when he drank too much. A friend, Herbie Worthington, was quoted saying that Hendrix “just couldn’t drink…he simply turned into a bastard.” Nobody is interesting unless their dark behaviors are at least acknowledged if not explored. It’s not a crime or even a significant failing to have had an alcohol problem. But it is a crime of sorts to try and erase everything biographical that doesn’t have a positive sheen.

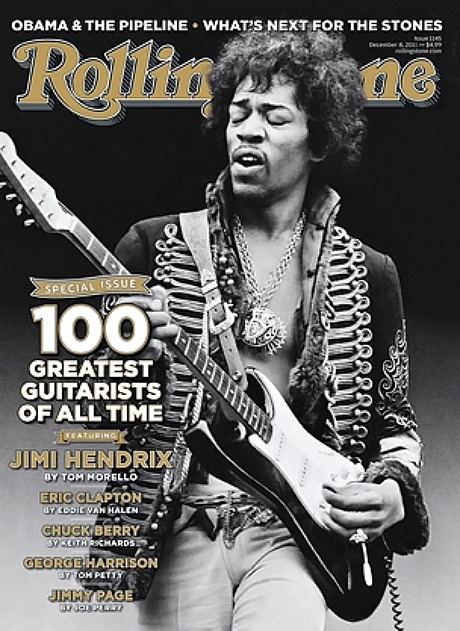

Nor does the doc explore his creative growth pains to any great degree. Although it includes a clip of a Rolling Stone critic saying that Hendrix “exercised the ultimate civil right” by doing whatever the hell he wanted to do with his music, he was known to have conflicted feelings in the later stages of his four-year reign about whether he was black enough in his attitudes and song stylings and public persona. Hear My Train A’Comin’ also doesn’t mention how some colleagues felt Hendrix never really successfully grew or evolved past the flashy feedback stage of ’66 to ’68 — Joni Mitchell speaks about this in a clip pasted just below.

Nor is there anything in the film that delivers the sadness and the anger that Eric Clapton felt about being abandoned and alone when Hendrix died. (Clip pasted below.)

But it’s still a likable and occasionally interesting doc. People applauded at the end of last night’s screening. If you don’t mind the idea of a somewhat whitewashed biography, you might as well enjoy it for what it is. There are several musical passages that look and sound terrific. It resuscitates the old vibes and currents. It lets you feel what Hendrix was all about.

The talking heads include Chandler, Paul McCartney, Noel Redding, the late Mitch Mitchell, Billy Cox, sound engineer Eddie Kramer, Lou Adler, Michelle Phillips, Steve Winwood, Vernon Reid, Billy Gibbons, Dweezil Zappa and Dave Mason.

The 1973 doc A Film About Jimi Hendrix had a lot more soul and feeling than this PBS version does.

Don’t forget that my ex-wife Maggie and I lived above Mitch Mitchell and his girlfriend in a house on Franklin Avenue, way up in the hills, from mid ’87 to late ’88. We gave Mitch and whatsername our credit references when we first expressed interest in renting the upstairs. I would run into him from time to time and shoot the shit, but I never sat down and grilled him about the Hendrix days. I should have.