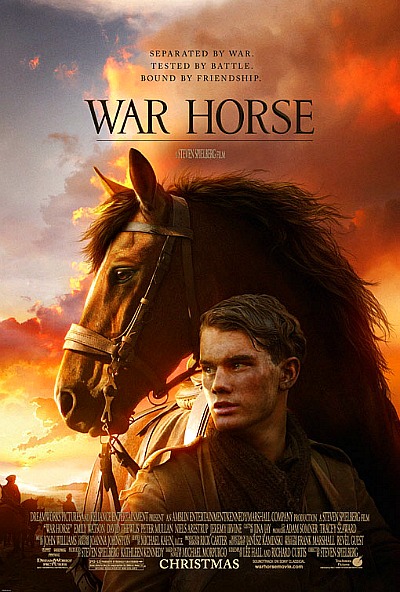

The beautiful amber-pinkish red sunset clouds and the obvious bond between Joey the horse and Albert (Jeremy Irvine) tell us that Steven Spielberg‘s War Horse (Touchstone, 12.28) is going to lay it on thick. This is basically going to be an emotional family-friendly film about caring and love and the romance of beautiful photography (by Janusz Kaminski, of course) and the always affecting strains of John Williams‘ score.

If you’re the sort of moviegoer who lives for stark, this-is-life, take-it-or-leave-it, matter-of-fact realism, chances are you’re going to feel a bit starved by War Horse in this respect. Maybe.

Which is fine in and of itself. There’s nothing wrong with making this kind of movie with this kind of material if it’s handled well. But a presumably studio-written synopsis that I found this morning on Coming Soon has scared me half to death.

“Set against a sweeping canvas of rural England and Europe during the First World War, War Horse begins with the remarkable friendship between a horse named Joey and a young man called Albert, who tames and trains him,” it reads. “When they are forcefully parted, the film follows the extraordinary journey of the horse as he moves through the war, changing and inspiring the lives of all those he meets — British cavalry, German soldiers, and a French farmer and his granddaughter — before the story reaches its emotional climax in the heart of No Man’s Land.”

“Changing and inspiring the lives of all those he meets”? Isn’t that what Lassie used to be do when she made her way across the Scottish and English countryside and running into farmers and children and constables and whatnot?

I’m always soothed whenever I meet a horse. I smile and feel good and want to pet him and tell him I like him a lot. That’s one thing. But does a horse inspire me and lead me to change my life? Animals warm our hearts but they don’t ‘inspire’ us. In fact, they explain us. The way you respond to an animal always reveals an aspect of who and what you are.

That is why the way the exploitive way the donkey was treated in Robert Bresson‘s Au Hasard Balthazar revealed the selfish and cruel side of human nature. The donkey was a kind of saint, a Christ figure, and he was constantly shat upon and used as a beast of burden by almost every working-class figure he runs into (except for a couple of female characters). But along comes War Horse delivering…what, the opposite message? That people are basically kind and decent and compassionate and that Joey brings this out in them?

I’m sorry, but that passage about “changing and inspiring” makes War Horse sound like sentimental slop.

Perhaps N.Y. Times critic Ben Brantley‘s description of the play provides a hint or two.

“I once attended a midnight show of Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, where the audience was heartily enjoying the carnage wrought by a man-eating shark until a pooch was seen swimming in the ocean, and someone seated near me, expressing the feelings of multitudes, called out, ‘Oh, God, not the dog!’

“War Horse taps that same keg of emotion. It’s ‘Oh, God, not the horse,’ elicited to bring home the savagery of war.

“The play also speaks, cannily and brazenly, to that inner part of adults that cherishes childhood memories of a pet as one’s first — and possibly greatest — love. This is a show for people who revisit films like National Velvet and Old Yeller when they need a good cry.

“In truth, the script of War Horse makes that of National Velvet (I mean, the heavenly 1944 movie, starring the 12-year-old Elizabeth Taylor) seem like a marvel of delicacy.”