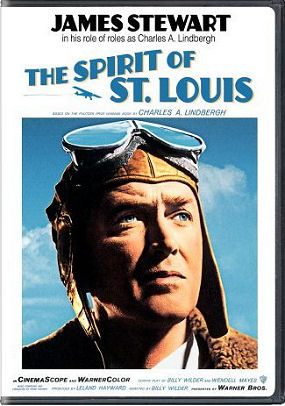

N.Y. Times DVD columnist Dave Kehr, whose dismissive snortings have prompted an occasional retort from this corner, has gotten it wrong again. In his current column he refers to Billy Wilder‘s The Spirit of St. Louis, a not-half-bad 1957 James Stewart flick about Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 solo flight from New York to Paris, as “stunningly impersonal.”

In terms of auteurist brushstrokes, he means. And Kehr is right — the film has none of the wit or subversion in Wilder’s best films, and it does seem as if Wilder made it for the paycheck. But in its mid-1950s, earnestly stodgy way, The Spirit of St. Louis is moderately watchable — it moves along in a steady, workmanlike fashion — but also pays off emotionally at the very end. In a blatantly dishonest way, yes, but effectively. And I’ve always found this fascinating.

It’s mainly because of Wilder’s storytelling discipline — he was always one to plant seeds and make them pay off much later in a film — and also, partly, due to Franz Waxman‘s music. But Kehr can’t be bothered to mention this, perhaps because he never realized it or is too smug to pay attention. I only know that I hate it when smart critics diss a film that’s at least partly successful.

Just before the exhausted Stewart is about to land his plane at Le Bourget field in Paris, he starts to lose it — he starts freaking and whimpering over a sudden inability to focus on the basics of landing a plane.

The movie has briefly acknowledged about an hour earlier that Lindbergh was an atheist who believed only in his own aeronautical skills and in the engineering of planes. But just as Stewart is melting down above Le Bourget he thinks back to a “flying prayer” that a priest passed once passed on, and he says aloud, “Oh, God, help me.” And of course he lands safely.

And I swear to God it seems like the right thing to say at that moment — for Stewart/Lindbergh, for the audience, for the film. And I’m saying this as a half- atheist myself. (I found satori when I was 20 — I held universes in the palm of my hand — but mystical flotation fades over time.) It was shameless of Wilder and coscreenwriters Charles Lederer and Wendell Mayes to have pulled such a cheap trick (pandering to conventional religious sentiment, etc.), but it’s amazing when bullshit works despite it obviously being bullshit.

Jean Luc Godard had a somewhat similar reaction when he said he was seized with affection for John Wayne‘s Ethan Edwards at the end of The Searchers when he picks up Natalie Wood and says, “Let’s go home, Debbie.” That’s a dishonest moment also — Ethan is a racist sonuvabitch, and there’s no way he’s doing to do a last-minute 180. But the moment works anyway.

I’ve always felt that any movie that puts at least one lump in your throat is not impersonal. If the filmmakers are talented and clever enough to “get” you, they’re always coming some emotional place themselves. You can’t be totally cynical and touch people. You have to mean it on some level. And that means getting down to the “personal”.