Elizabeth Taylor: The Lost Tapes, which began streaming yesterday on Max, is an attractive, watchable gloss that plays it safe and tidy at every turn. It’s a valentine — nothing funny or nervy or the least bit impudent. No Larry Fortensky jokes. No clip of John Belushi‘s “Liz choking on chicken bones” skit. Not so much as a glance at Ron Galella‘s Fat Liz photo.

Director Nanette Burstein deserves a certain kind of cynical credit for sanding every possible edge off the legend of La Liz. So much material has been ignored. Too damn friendly.

Even the brief mention of Taylor’s suicide attempt during her marriage to Eddie Fisher feels somehow soft, mainly because it doesn’t make sense.

Sometime in ’79 or ’80 I saw Elizabeth Taylor in the flesh. She was standing about ten or twelve feet away in a dense crowd of guys at an after-party at the Roxy, the popular Manhattan roller disco on West 18th. I managed a glimpse or two of her eyes, and was slightly surprised to discover that they really were as beautiful as I’d been told. I was mesmerized. I think I actually said out loud, “Wow.”

I’d been looking at Taylor in film after film all my life, of course, but those real-life peepers had an extra-glistening, pools-of-passion, send-your-hormones-to-the-moon quality that I’d never quite gotten from a live female before. And they actually did seem to be violet colored, as legend had it.

The once-legendary Taylor hit her career peak between ’51 (A Place in The Sun) and ’60 (Butterfield 8). This was also when she seemed the most erotically enticing.

I heard and read a lot about her over the decades, and gradually became persuaded that she was tough and real and super-loyal to her friends…although I never understood why she befriended that freak known as Michael Jackson.

I had read once that Taylor saved Montgomery Clift‘s life just after his 5.12.56 car crash by extracting a dislodged tooth that had been stuck in his wind pipe. By all accounts she was a good person to know and share time on the planet with, and also that she was feisty and steady and reliable and no fool. And she liked to drink and have fun and laugh through it all….hah!

I think, in short, that she might have been a better person than she was an actress.

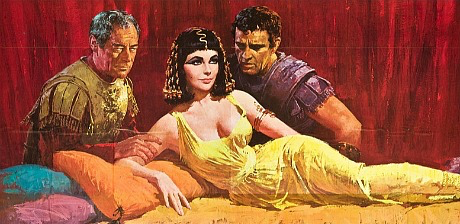

I’m not dismissing her very good ’50s performances in A Place In The Sun, The Last Time I Saw Paris, Giant, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Suddenly Last Summer and Butterfield 8. But she was seriously miscast in the lusciously miserable Cleopatra, and with the exception of her brilliant, possibly all-time best performance in Mike Nichols‘ Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, she stopped getting the good roles after that and just wasn’t a very interesting presence in the ’60s and ’70s.

Taylor was pretty much out of the game by the early 80s.

Her golden time was the 1950s, period, and she was at her hottest back then also. She started to put on weight after Butterfield 8 (i.e., after she hit her early 30s), and the hard truth is that she looked vaguely plump in Cleopatra, and that roundish, slightly boozy and besotted look never went away after that. I’m sorry but that’s how it pretty much was. But those eyes of hers were givers of rapture and splendor.

My only other first-hand connection with La Liz came with my numerous sleepovers at the Nicky Hilton-Elizabeth Taylor house on Route 102 in Georgetown, Connecticut, as the guest of the late cartoonist Chance Browne. It’s a small cottage where Hilton and Taylor stayed for a period in 1950 during their brief rocky marriage before she sued for divorce (she complained of spousal abuse) — local legend says Hilton threw Taylor out a window during one of their drunken fights.

There’s really not much feeling in Burstein’s film. It’s too admiring, too subservient to generate anything that truly hits home.