I’ve been a Paddy Chayefsky fanatic for as long as I can remember, but until last week I’d never seen Middle of the Night (’59), a May-December romance drama that Chayefsky adapted from his stage play. It meant having to buy a whole Kim Novak DVD package but a voice told me right away, “Now is the time…you can’t put off seeing a serious Chayefsky work, even a lesser one, any longer. Do it.”

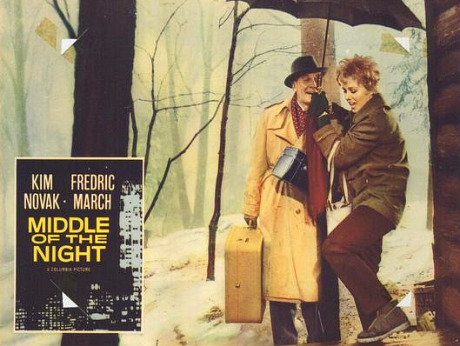

It’s about Fredric March, a recently widowed 56 year-old who runs a Manhattan clothing business, having an affair with Kim Novak, an insecure 24 year-old divorcee. It’s a grim, grim film — even the off-screen sex feels like a vague downer of some kind. But it also feels honest and even courageous in the sense that relatively few 1950s films painted frank portraits of big-city despair and depression.

Middle of the Night is a dirge — the kind of movie that you can easily respect but otherwise requires a certain effort to get through. Right away I was telling myself “this is good but I’m not enjoying it, but I’m determined to stay with it to the end because it’s a Chayefsky thing and is obviously well acted, especially by March and Novak and Albert Dekker, and because it has some fascinating 1959 footage of midtown Manhattan and yaddah-yaddah.”

When I say “well-acted” I mean according to the mode and style of 1950s acting, which tended to be on the formalistic, speechifying, straight-laced side. (Which is why the internalized styles of Brando, Clift and Dean were seen as huge breakthoughs.) I found myself wishing that director Delbert Mann has asked everyone to tone it down a bit. Nobody mutters or stammers or speaks softly, or struggles with a thought.

Middle of the Night is about loneliness and guilt and fear of social judgment that you’re not behaving as you should (or as your family wants you to behave), and the opposing notion that you may as well lunge at whatever shot at temporary happiness that comes along because life basically sucks and no one gets out alive. It feels cleansing to come upon an Eisenhower-era drama that admits that a fair percentage of people are miserable (even or perhaps especially those who are married) and explores this situation in some detail, and with the usual blunt eloquence that you get from any Chayefsky work.

The original stage play is described as a “comedy”? By what planetary standard?

Everyone in the cast (including Lee Grant and Martin Balsam as March’s daughter and son-in-law) walks around with a certain melancholy under their collar, unhappy or at least frustrated but committed to keeping up “appearances.” God, what a self-torturing way to live!

A drama about a love affair has to have some kind of basic chemistry going on. There are some couples you can accept as lovers in a film or a play, and others you just can’t. And I’m sorry but I was having real trouble imagining a perspiring, buck-naked March sliding and slithering atop a damp and moaning Novak. Just writing that sentence creeps me out even now. There are some people you’d rather not think about in a sexual context and the older March, beginning with his performance in The Best Years of Our Lives (’46), is one of them — no disrespect intended. His Middle of the Night character is supposed to be in his mid ’50s but March was around 61 or 62 when the film was shot, and he was evidently never much of a 24 Hour Fitness guy to begin with. By today’s standards he looks at least 70 if not older. So it feels very weird and strange that Novak would even half-entertain the idea of doing this guy. Then again March always seemed genuine and grounded as an actor — you always believed he really felt what he was saying.

Choice Middle of the Night dialogue (courtesy of the IMDB):

Jerry Kingsley (i.e., March’s role): “Listen, sonny boy. Love, no matter how shabby it may seem, is still a beautiful thing. Everything else is nothing.”

Walter Lockman (i.e., Dekker’s part): “I haven’t had ten cent’s worth of life! Not a dime! Believe me!” And this: “When they bury me, they can put on the gravestone, ‘This was a big waste of time.'”