Paramount’s decision to boot Joe Wright‘s The Soloist out of the ’08 Oscar season and into a late spring ’09 release was a message to the masses that it didn’t work as an awards-level thing and perhaps not even in a regular-paying-audience sense. And now the opening-day reviews — a lousy 54% positive from the Rotten Tomato grunts and a marginally better 65% positive from the creme de la creme — seem to underscore that.

But it’s far from a disaster. You could call it mildly disappointing but I wouldn’t. Not altogether, I mean. Somebody wrote something about it being a kind of magic negro tale — a movie about how a black guy with amazing spiritual currents saves a white guy from becoming too wussy or distracted or divorced from life’s essential bounty. Parts of The Soloist seem to work that end of the room, but…honestly? I just can’t work up a head of steam about this film. And yet it’s very decently crafted and smartly acted. A not-unsatisfying sit as far as it goes.

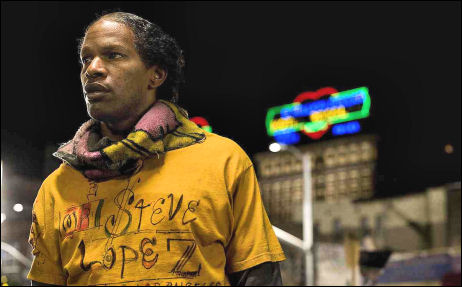

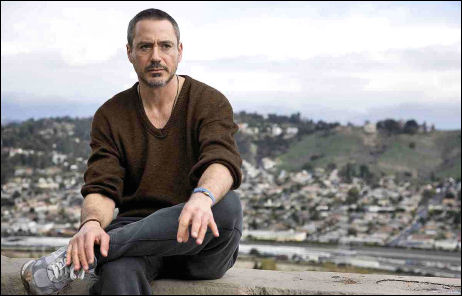

It’s based on a book of the same title by L.A. Times columnist Steve Lopez. The subtitle of the book: “A lost dream, an unlikely friendship, and the redemptive power of music.” Sounds like a movie, doesn’t it? Except I’m not sure after seeing the film that it’s the greatest story or the most inviting subject in the world. The basic drill concerns Lopez (Robert Downey, Jr.) seeing a story in a schizophrenic street guy (Jamie Foxx) who plays a mean bass viola, and who turns out to be a disturbed musical genius named Nathaniel Ayers.

Lopez begins to write columns about Ayers as well as take him on a personal aid-and-assist project. Ayers is saved from the streets and winds up at the end in a somewhat happier or at least less anguished state; Lopez learns about classical music, about the horrors of being mentally ill and itinerant, and — here’s the movie-pitch part — to be a slightly better (i.e., more giving) human being.

And yet The Soloist is not Shine. The fulfillment-achieved-at-the-climax formula is not strictly followed, and I respect that. But it doesn’t really have what I’d call an “ending,” and the bottom line is that you’re saying to yourself as it comes to a close, “That was nice but…wait, what was it actually about?”

The theme is a Yoda-type thing, i.e., “Do or not do — there is no try.” If you’re going to be a friend to someone, be a friend all the way without any mucking around. There’s no room in friendship for halfway measures or dilletanteism. This is the Dr. Phil life lesson that Lopez learns at the end, or something close to this. I sat there and went, “Uh-huh, fine, whatever.” My sister was schizophrenic for most of her life so I know whereof I speak. I also know it’s all about meds — either they take them or they don’t.

Foxx’s performance did remind me of my sister when she was in a really bad way, back in her late teens and early 20s. Schizophrenic states let the light in in an R.D. Laingian way, yes, but it also beats the body and spirit to a pulp. It’s a horribly turbulent and stressful thing to deal with — a force that constantly hammers and agitates. Foxx conveys that with vigorous accuracy. He’s clearly gotten into that hyper place in his head (and it’s no place you want to get close to if you can avoid it — trust me). It’s a seriously admirable performance.

And Downey is fine. He’s playing a focused, low-key, hard-working, highly stressed journalist. I know a little something about that world (although I’m more of a keyed-up type) and I believed him so…whatever, leave him alone.

I admired and was actually grateful for Wright’s visual attempts to get into Foxx’s head when he’s playing or listening to music. At one point Wright sends the camera soaring above the streets in a way that recalls the floating-feather sequence in Forrest Gump, and in another on a kind of voyage into a crimson cosmic kingdom that vaguely resembles the famed light-show finale of 2001: A Space Odyssey. It’s not that these sequences are dazzling — they’re just okay — but at least Wright is trying to use the camera in a semi-audacious way.

We’re living through a fairly timid age from a cinematography perspective. In film after film all we seem to get is routine coverage from various angles. Remember that Simon & Garunkel montage in The Graduate when Dustin Hoffman leaps out of the pool and onto his floating air mattress, and how in the blink of an eye the mattress becomes Anne Bancroft sighing after sex? Nobody but nobody does stuff like this any more, so give Wright points for at least attempting to venture beyond.