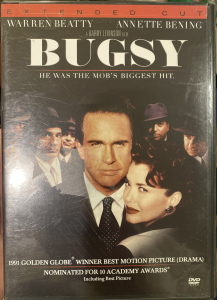

There’s no question that the extended version of Barry Levinson, Warren Beatty and James Toback’s Bugsy, which runs 151 minutes or 15 minutes longer than the original 136-minute theatrical version, is a distinctly superior work.

N.Y. Times DVD columnist Dave Kehr notes that “the extended version of Bugsy that Sony Pictures Home Entertainment is releasing today adds 15 minutes of material, restoring what most of its participants saw as the finished version of the film before it was reportedly recut by Mike Medavoy, then the chairman of TriStar Pictures.”

(This may be incorrect: Bugsy screenwriter James Toback told me this morning that Medavoy declared that an early cut was “too long”, but he didn’t seize the print and have it recut in defiance of director Barry Levinson or producer-star Warren Beatty. On the other hand, Kehr, an exacting critic, got his information from Toback also. Kehr says it was recut by TriStar, but did not report that the film was taken away and recut against anyone’s protest.)

“With the seamlessly restored shots and sequences,” Kehr remarks, “the picture plays much more smoothly and inexorably than it did in the edited version. Bugsy Siegel’s rise now has the classical contours of tragedy, complete with a hero whose hubris — his vision of founding a city in the desert — comes in conflict with the gods, or at least those East Coast capos who controlled the purse strings.

“The most striking addition comes after Siegel (Beatty), a New York hood who has gone to Los Angeles to conquer the local rackets, is forced to execute an old friend (Elliott Gould) for informing. Filled with self-loathing, he returns to his Hollywood home and puts a gun in his mouth. The sequence is the film’s most precise revelation of Bugsy’s fatal flaw: he’s a gangster cursed by self-awareness and a growing moral sense.

“Released in 1991, Bugsy may have been a film with too many fathers. Beatty, who co-produced this dark, sensual, morally conflicted biography [and] who played [Siegel] with a Tony Curtis-like striver’s elegance, was of course the director of the acclaimed Reds. Toback was (and is) a passionately first-person artist who drew freely on his experiences in films he had both written (The Gambler) and directed (Fingers, Exposed). And Levinson was then at the height of his commercial potency, having turned out Tin Men, Good Morning, Vietnam and Rain Man in dizzyingly quick procession.

“Bugsy would not have been the densely detailed and complexly imagined film that it is without the contribution of any one of these men. But one wonders what might have resulted had the authorial strands been pulled apart and had Beatty been able to make another of his studies of an American naif (following Clyde Barrow of Bonnie and Clyde, George the hairstylist of Shampoo and John Reed, the radical journalist of Reds) blundering as best he can through the social upheavals of an era; or had Toback, with his fascination with sex, power and the romantic fatalism of the gambler; or had Levinson fully indulged his nostalgia for a lost era of sartorial elegance and tastefully lighted interiors.

“Levinson was the dominant force on the set, and the film duly reflects his fundamentally comic sensibility (even when the material dips into darkness) and affection for attention-grabbing period detail. Pulled in so many directions at once, Bugsy lost its center. Was it a steamy romance (with Beatty’s Siegel falling hard for a tough-talking bit player named Virginia Hill, played by his wife-to-be, Annette Bening), a harsh parable about American capitalism or a period film dripping in sweetly nostalgic detail?”