Not Bali Hai

Steve James’ Reel Paradise is lying in wait at your local theatre like a King Cobra. Buy a ticket and watch it and it will bite you and poison to death any Marlon Brando Mutiny on the Bounty South Sea island fantasies you may be nurturing in your soul.

Paradise says that watching a good movie can create a kind of paradise in your head, and that turning people on to an exciting or nourishing film can be a wonderful thing. It also says that an alleged tropical getaway like Fiji (and, by extension, other South Sea locations) can be vaguely boring and economically strapped with thieves ready to sneak in and steal your computer if you’re not careful.

The Pierson family (l. to r.): Georgia, John, Janet, Wyatt in Steve James’ Reel Paradise

And you’d better watch out for your teenaged daughter while you’re there also because life is a struggle and a pain everywhere, and nothing about South Sea life is particularly safe or comforting or tranquil. In short, there are no getaway places. Your life is your life and that’s that.

I don’t know why I used the image of a King Cobra to describe this film. It’s more of a mongoose, really. A thoughtful life-can-be-gnarly-but-whaddaya-gonna-do? movie made by folks I happen to know and like and respect.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

I guess all I’m really saying is that I don’t think I’ll be visiting Fiji during my next South Seas vacation, but if you’re looking to spend your movie money this weekend on something more substantial and alert than Judd Apatow’s The 40 year-Old Virgin, here’s a good alternative.

It’s a doc about what happened three years ago to John Pierson — the former “Split Screen” host, movie-book author (“Spike, Mike, Slackers & Dykes”), producer’s rep and all-around movie community good guy — during a year-long stay in Taveuni, Fiji, where he and his family showed free movies to the locals at a place called the Meridian 180.

Pierson discovered this funky, barn-like theatre on a visit to Tavenui — an agricultural island of about 10,000 residents — in 1999. When the Meridian shut down in ’02 Pierson somehow managed to buy it and then talk his family — wife Janet, 16-year-old daughter Georgia and 13-year-old son Wyatt — into making the trek.

John Pierson addressing crowd at Taveuni’s Meridian cinema prior to another night’s showing.

And then James showed up with his camera in the summer of ’03 to document the final month of their stay. And what he got is that life without cultural resources or the usual modern-age distractions can be a bit flat. Taveuni is a poor island with no public electricity, no high-end restaurants, no video rental stores…Nothingville.

But the film also shows that good movies can have a kind of religious effect upon the locals, and that Pierson became, during his stay, a kind of parish priest.

Gut-level movies — comedies, thrillers — fared the best here. The Fiji folks haven’t have much education and are fairly low-rent in their tastes. They want to laugh or be thrilled or be scared. You get the idea that even if prints of, say, films by Robert Bresson were available to Pierson in Fiji, he wouldn’t have dreamt of showing them.

The obvious association is the scene in Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels when the chain-gang prisoners start laughing uproariously at a Pluto cartoon. A good laugh is all some people have, etc.

The biggest real-life issue in the film is computer robbery and the suspicions that arise about which local might be the culprit. Plus the projectionist Pierson has hired is a real slacker. And there’s also Georgia’s involvement with a local kid whom her parents have reason to disapprove of.

Georgia Pierson (l.) and friend in Reel Paradise.

Put aside the movie-religion aspects and Reel Paradise boils down to a series of lessons about what a real downmarket tobacco-road place Taveuni is, a laid-back culture without much to attract people like myself.

Variety critic Todd McCarthy says Reel Paradise is analagous in some ways to Peter Weir’s The Mosquito Coast. As I watched it I was thinking more about Franklin J. Schaffner’s Papillon.

My mind was also drifting back to that speech that Kirk Douglas gives in Ace in the Hole about the four spindly trees in front of Rockefeller Center providing more than enough in the way of nature’s splendor, etc.

Being There

Almost no one paid to see The Great Raid when it opened last weekend, and most of the critics were bored by it. (It only got a 36% favorable on Rotten Tomatoes.) I wasn’t exactly over-the-moon about it myself, but at no time did it anger or frustrate me, and there’s a kind of distinction in that.

The one aspect that got me 100% was the decision on the part of director John Dahl to make an anachronistic war film. The Great Raid isn’t boring, exactly – it’s just a movie that’s true to the era its depicting, and therefore feels out of synch with our times. Which, of course, is partly the point.

The Great Raid is a 98% true World War II story, and not just in factual terms. It’s the story of a raid in early 1945 by a commando team of about 100 soldiers and volunteers, led by some U.S. Army noncoms, upon a Japanese prison camp in the Philippine boonies. It led to the freeing of just over 500 prisoners, soldiers who might have died at the hands of their captors if the raid hadn’t happened.

Benjamin Bratt, James Franco in John Dahl’s The Great Raid.

You can say, “Yeah, and so what?” But this is what the movie’s about, and Dahl has not only paid respect to the story but the era when it happened.

Is The Great Raid the most suspenseful, excitingly paced war film you’ev ever seen? No. It’s not exactly sluggish but it feels…dutiful. A movie “doing its duty” in trying to recreate a bygone era by adopting an anachronistic style. And in this sense Raid‘s stolid qualities — the feeling that it might be your grandfather’s idea of a satisfying World War II film — work in its favor.

Not in its commercial favor, obviously, but Dahl did what he did for the right time-machine reasons.

It isn’t just that Dahl has heaped on period realism in terms of dialogue, character shadings and carefully-chosen props and wardrobe (guns, uniforms, women’s hair styles…all highly authentic and just so). It’s also the stolid framing and the unhurried old-fashioned pacing of the thing. It’s Dahl saying to us and himself, “To hell with 21st Century action movie appetites and standards…we are not playing that game.”

The only here-and-now aspect is the faded, sepia-like color…but even the desaturation seems to line up with the old-fogeyness of the thing. It opens the door to an imagining that an original version might have been shot in vivid Technicolor but then faded over the years.

Day-for-night still from The Great Raid,meaning this scene looks a lot duskier in the actual film.

The Great Raid doesn’t feel as if it was shot in ’45 and then put in a storage facility and kept there for 60 years. It would have to have been filmed in monochrome in a 1.33 to 1 aspect ratio to achieve that illusion. But it does feel like it could have been made in 1955 or thereabouts. If this had actually happened it would have costarred Aldo Ray, Jeff Chandler and George Nader.

As is, the performances (by Benjamin Bratt, James Franco, Joseph Fiennes, Connie Nielsen, Marton Csokas) feel like earnest imitations of the kind of acting that Bill Holden or Jeffrey Hunter or June Allyson used to deliver in boilerplate war flicks of the 1950s.

And I admire the exacting ways that Dahl made it feel so old-fashioned. He knew there would be critics saying “too slow” or whatever, but he was too hard-core to spritz it up (like some period films I’ve seen) and make it feel, say, like a film that was half ’45 and half ’05.

I could go on and on about period films that got the haircuts wrong or had performances or dialogue that felt wrong. It’s not rampant but it happens. Period films are sometimes over-d√É∆í√Ǭ©corated or over-polished. The cars are too new or the actors are too present-day in their speech patterns or accents, or there’s too much CGI (like in Troy).

Marton Csokas in The Great Raid

You can argue that the verisimilitude in The Great Raid doesn’t matter that much because the story plods along and there’s not enough in the way of suspense or story tension, and I wouldn’t argue with you. But I didn’t mind it too much because the period immersion is so complete.

And I just had to slap myself to keep from nodding out. I am boring myself as I finish a piece about a movie that’s a little bit boring for the right creative reasons.

Honest footnote: I have to admit that I was glad when the Japanese soldiers dragged Csokas (the lover in Paramount Classics’ Asylum) and shot him in the head. Csokas speaks with an oddball accent in the film hat includes a bizarre throaty sound he gives to vowels, and so I was glad to rid of him.

By The Way…

Another movie that gets it right in a historical atmosphere sense is George Clooney’s Good Night and Good Luck, which I saw the other night.

It’s not just that the factual newsroom tale, which happened in 1954, has been shot in black and white, but that it feels like one of those live high-quality 1950s television plays, which were routinely seen on Kraft Television Theatre (ABC, 1953-55), Four Star Playhouse (CBS, 1952-56), Ford Theater (NBC, 1952-56) and so on.

David Straitharn in Good Night, and Good Luck

My immediate response was that I really liked and admired the austerity and the realism of Good Night, and Good Luck. It felt like it was happening in the actual 1954…almost. It didn’t feel like ’54 by way of 2005…and I liked that it got right down to the matters at hand and stayed with them.

It really is terrific when you feel a filmmaker striving as hard as Clooney, who costars as well as directs, to give a sense of time and place and also the mentality that informed an era…the way it most likely felt.

I probably won’t get into the merits of Good Night, and Good Luck until it shows at the New York Film Festival in late September (Warner Independent is opening it on October 7), but it’s a thoughtful, respectable film with first-rate acting and an honorable theme and a terrific performance by David Straitharn as legendary newsman Edward R. Murrow.

Honor of Lying

From a celebrity’s perspective, truth-telling is a selective process these days. That’s a way of saying that pretty much every celebrity lies right through his or teeth when it comes to public statements. But it’s okay because they’re well motivated.

They’re lying because they despise the media and feel that dealing with a corrupt and disreputable entity means all bets are off. And I think I understand the ethical system they’re embracing because it was explained in a couple of respected ’60s westerns.

Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch is one of them. I’m thinking of a scene in which William Holden’s Pike Bishop expresses moral support for Robert Ryan’s Deke Thornton because he gave his “word” to a bunch of “damned railroad men,” and Ernest Borgnine’s Dutch Engstrom defiantly argues, “That ain’t what counts! It’s who you give it to.”

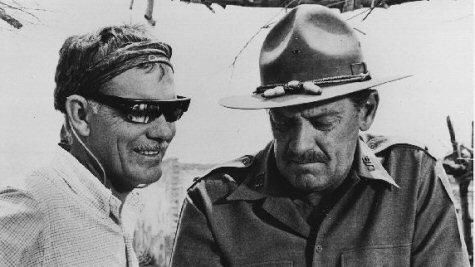

Director Sam Peckinpah, star William Holden on the set of The Wild Bunch

Burt Lancaster says the same thing in The Professionals when he discusses flexible ethics with Lee Marvin. When Marvin reminds Lancaster that he’s given his “word” to Ralph Bellamy’s J.W. Grant, a millionaire railroad tycoon, Lancaster replies, “My word to Grant ain’t worth a plug nickel.”

Tom Cruise is J.W. Grant-ing, in effect, when he says he’s in love with Katie Holmes and wants to marry her and so on. He’s saying, “This is what you’re going to get from me and if you don’t think I’m being honest then that’s too fucking bad because my life is my own and you guys don’t rate the real truth because you’re scumbags and you pass along tabloid fairy tales.”

Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie lied and lied and lied and lied (and told their publicists to lie and lie and lie and lie) about their relationship, and they felt just totally fine about it because their word to the tabloid press is commensurate with the degree of respect they have for it.

I don’t really believe this, but I like to tell myself that Bill Clinton lied about his history with Monica Lewinsky because he felt that the news media (and the Republicans pushing things along in the late `90s) had no honor or legitimacy in trying to explore his sex life. Looking right at the TV cameras and saying nothing happened was completely honorable because the news media deserved to be lied to.

I can see this. I can see how people being hammered about personal matters might start thinking this way. But then again…

If you’re willing to lie to someone you’ve opened the door to dissing them in other ways. Just as Lancaster and Holden and friends were fine with lying to railroad men as well as stealing their money and possibly shooting them during hold-ups, I’ll bet celebrities are thinking about different ways of smacking around tabloid reporters.

That photographer who got shot with a BB pellet while standing outside Britney Spears’ Malibu home…? Just the beginning.

9/11 Movies

“Do we really need dramas about 9/11 so we can exploit the tragedy and suffering and add to the hysteria? It’s bad enough we have a manufactured war. Do we need manufactured crap to incite us further?” — Edward Klein

“I don’t know what bothers me exactly about the 9/11 movies coming out. There were plenty of movies about WWII, and a lot of them made during the war, but those were sort of rah-rah propaganda movies about a war that was absolutely necessary. The Vietnam films seemed hell-bent on showing us the real story behind a war that no one seemed to understand, and many of them revealed the suffering that the troops went through before and after the war.

“But those 9/11 films that are being prepared seem pointless. Why make one? What…there’s no actual footage? People have yet to see what happened? That’s not an argument since it was the single most videotaped event in the history of the world.

“So it must be a desire to reveal what people inside the towers and their families have dealt with during and since that day. No, since there have been countless news reports and documentaries and books and official reports letting us know the horrors of the attack and it aftermath.

“So what could possibly be motivating filmmakers about to start on their 9/11 movies…?

“The whole thing reeks of sickening commercialism. Greedy Hollywood vulture fuckheads who have no shame in exploiting people’s emotions and patriotism for a buck. This is example #5930 of how Hollywood is bereft of ideas. And I love how these guys have somehow talked themselves into thinking that they’re going to be doing some kind of service to mankind.

“It reminds me of the moment at the Oscars when James Cameron, holding his Best Picture award, asked the bejeweled, collagen-injected crowd for a moment of silence in memory of the victims of the Titanic disaster. It was both tasteless and ridiculous, and that event was almost 100 years old at the time. Just imagine how tasteless and ghoulish a 9/11 movie will be a mere five years after the tragedy.” — Mark Smith.

“I don’t see much in a script that attempts to retell an individual story from the events of 9/11. Anyone with a digital cable box can see documentaries from every point of view nightly on cable . HBO had an effective film several years ago that told the story of a boy whose mother was stuck in the towers and died that day.

“Hollywood could use 9/11 in a plot device for a romance — strangers fall in love while searching for a mutual friend who is missing. A sci-fi scenario where a character time travels and ends up in the towers. I think an audience could be accepting of 9/11 in film as long as it is not that literal. Spike Lee effectively used 9/11 subtly as a minor character in 25th Hour. — Ken Ridge, Hazlet, New Jersey.