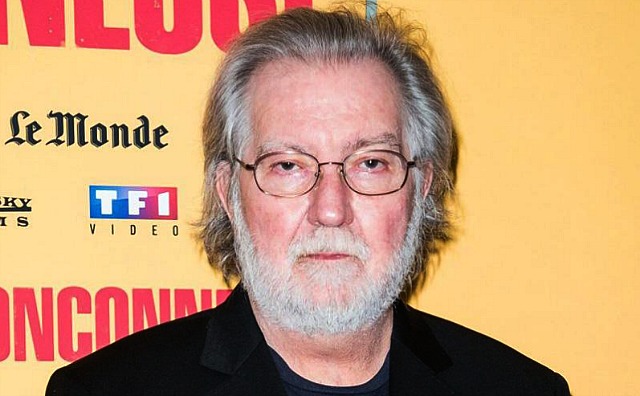

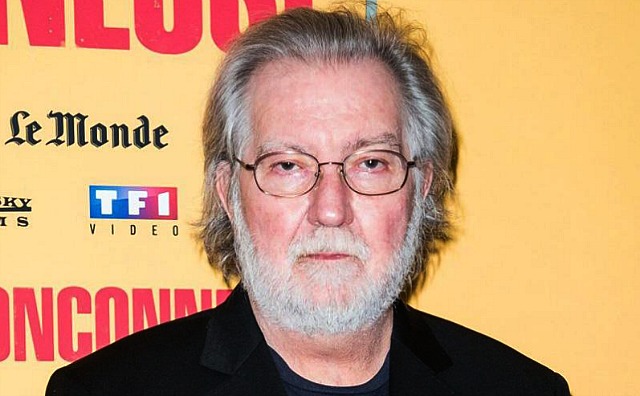

Hugs and condolences for the friends, fans and colleagues of influential horror film maestro Tobe Hooper, who died yesterday at age 74. There’s no question that Hooper did himself proud with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (’74), a low-budget slasher thriller that I’ve never liked but have always respected. The following Wikipage sentence says it all: “It is credited with originating several elements common in the slasher genre, including the use of power tools as murder weapons and the characterization of the killer as a large, hulking, faceless figure.”

Hooper made a life out of his facility with horror. He career-ed it to the max. But after The Texas Chainsaw Massacre he never struck the motherlode again, not really.

You can’t give Hooper serious credit for Poltergeist, which was mostly directed by Steven Spielberg. And no, I’m not a fan of Lifeforce. If you want to be cruel about it you could call him a feverish, moderately talented fellow who got lucky only once, and that was it. Hooper was tenacious and industrious and always kept going, and of course he dined out on the original Saw for decades. No harm in that.

L.M. Kit Carson, the renowned screenwriter, producer and journalist whom I proudly called a friend and ally from ’86 until his passing in 2014, was friendly with Hooper. They shared a Texas heritage and worked together on The Texas Chain Saw Massacre 2 (’86), a misbegotten piece-of-shit sequel that Cannon Films produced and which I, a conflicted Cannon employee at the time, wrote the press notes for. Carson introduced me to Hooper as a gifted writer who really understood the satirical tone of Carson’s brilliant Saw 2 script. If only Hooper had absorbed it as fully and translated it to the screen with a similar panache.

Carson wrote a tangy piece about Hooper for the July-August ’86 issue of Film Comment, called “Saw Thru.” Here’s an excerpt that explains the genesis of TTCM:

“Near broke at Christmas ’72, Hooper got tangled in the last-minute-shopper mob at a Montgomery Ward and shoveled into the heavy equipment department. Suddenly he was standing face to face with a big wall display of glinting chainsaws. All sizes. Row above row. An uneasy-making sight mixed with the tinsel, bright Christmas balls, red ribbons. Whu.

“And an abrupt Christmas crackup thought flicker-lit a few of Hooper’s brainy synapses: Quickest damn way out of here tonight is just to yank-start one of those chainsaws and cut a path to the door. It was a joke, but only a half-joke. An image that sold itself a bit too strongly.

“Hooper got the hell out of Montgomery Ward, went home with a chainsaw in his brain, and starred piecing together a movie. ‘In about 30 seconds I saw the movie right in front of me,’ he said.”

Here are six things I know or believe about Hooper, based on personal experience.

(1) As editor of The Film Journal, I began hearing in the early summer of ’82 that Hooper hadn’t really directed Poltergeist. Then I ran a freelancer’s interview with Poltergeist producer Kathy Kennedy in which she more or less confirmed that Spielberg had to step in and take charge because of Hooper’s overly deliberative approach to directing. Many articles have since reported or contended that this was the case.

(2) Carson’s screenplay for The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 was a total peach — a dry, darkly comedic kill-the-yuppies thing. It was heralded and excerpted in an issue of Film Comment; it might have been Harlan Jacobson who wrote “it’s okay to like it”. Alas, Hooper totally fucked it up. The sly social satire stuff was totally out the window. I was there for the very first in-house screening. The movie was shit.

(3) During Saw 2 post-production Hooper was working out of a third-floor office inside Cannon headquarters. I was working with other publicists on the fourth floor. I had put together a rough, raggedy draft of the Saw 2 press kit. Having briefly bonded with Hooper over our mutual Carson friendship, I foolishly decided that Hooper might appreciate being shown the draft so he could correct, add or subtract whatever he liked or didn’t like. So what did he do after I dropped it off? He called my boss, Priscilla McDonald, to angrily complain about something he didn’t like instead of calling me into his office to dictate changes. I got chewed out royally by McDonald (“Don’t upset him…you have to be more careful!) Thanks, Tobe!

(4) He was on the short side, maybe 5’6″ or possibly 5′ 7”. I remember looking down at him as we stood in his office once.

(5) The word around Cannon was that Hooper had issues with cocaine, and that it had gotten in the way of his effectiveness for a long while. I never personally saw Hooper snort anything but everyone kept saying that nose candy was a problem or had been a problem, so maybe there was something to it.

(6) Hooper’s Cannon follow-up, a remake of Invaders From Mars that costarred Carson’s son Hunter, was also a whiff and a bust. Reviewers universally hated it, and it only made a lousy $4,884,663. I recall visiting the sand-lot set on a sound stage and being very excited about the potential, but Hooper couldn’t make it fly, much less sing.

I wrote Hooper off after Invaders From Mars. He made several films in the ’90s and early aughts that I never saw. His last film was a supernatural thriller called Djinn (’13). Until this morning I’d never even heard of it, much less read reviews. But Hooper deserves respect. He was certainly part of landscape of the ’70s and ’80s. He made a name for himself. Every cineaste knew (or knows) who he was, and that ain’t hay.