Sock That Choppy

I loved Crouching Tiger and all, but it’s no secret there are more ardent fans of martial-arts movies than myself.

I like aerial chop-socky the way I like musical numbers in a ’50s Arthur Freed musical — visually exciting and beautifully performed, etc., but if there’s too much exposure to restricted worlds of this sort you can start to go a bit nuts. Sublime choreography, Chinese mythology, inspired cutting…I get it but all right already.

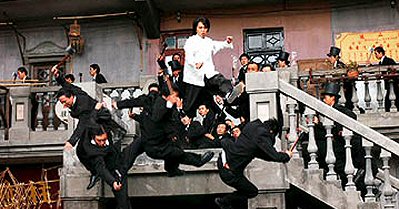

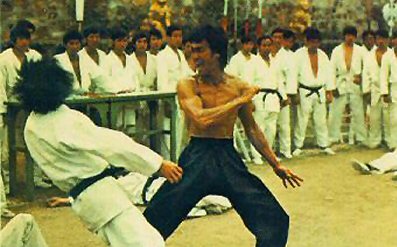

Kung Fu Hustle Stephen Chow performing obligatory single-hero-vs.-eighty-bad-guys fight sequence…done before by the Wachowski brothers and Quentin Tarantino, but never so hilariously.

That said, Stephen Chow’s Kung Fu Hustle, which I saw last night at the L.A. premiere at the Arclight, is truly something else. Part parody and partly a genre redefiner, it’s easily the funniest and most imaginatively nutso chop-socky flick I’ve ever seen.

Sony Classics is opening Hustle in New York and L.A. on April 8th and wide on April 22nd, and I can’t see it not being a huge action hit. If you’ve got genre skeptics like me saying it’s cool, you have to figure the action fans will be all the more enthusiastic….right?

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

Chow is a friendly, mild-mannered sort in person (we spoke last night at an after-party at The Palm in West Hollywood), but creatively he’s quite clearly a madman. Mad like Mozart or Picasso or Orson Welles. In the grip of a fine madness….unbound and flying on faith.

Kung Fu Hustle is not just imaginative and off-the-planet….it’s insane.

You can argue that when a genre film starts veering into genre parody, that’s the beginning of the end…but maybe not. The James Bond films were getting heavily spoofed in the mid ’60s and they’re still around.

Stephen Chow at West Hollywood’s Palm Restaurant– Tuesday, 3.29, 10:05 pm.

Maybe Chow-styled lunacy is what the martial arts genre needs at this stage. Even more illogical and indulgent…losing its mind and taking a leap off the cliff.

Chow, 42, is obviously the new Jackie Chan. He’s a longtime martial arts devotee and fan of Bruce Lee known for nonsense humor (which is apparently known as “moleitau”) and playing the fool. The only other film I’ve seen of his is Shaolin Soccer , which was released in ’01. I haven’t seen Chow’s God of Cookery or King of Comedy, but I can guess what they were like.

Hustle is an effects-driven Hong Kong goofball comedy (i.e., “comedy-fu”) by way of The Matrix .

The setting is some urban pre-Communist Chinese burg, and the plot is about a gang war of sorts between the inhabitants of a slum called Pigsty Alley (which isn’t an alley but a big U-shaped tenement) and the top hat-wearing Axe Gang, which is run by Brother Sum (Chan Kwok-kwan).

Chow plays Sing, a comic kungfu smartass with a fat sidekick (Lam Tze-chung), who eventually turns out to be a man with a mission in the Keanu Reeves/Matrix mold.

Special menu for Kung Fu Hustle dinner at Palm restaurant — Tuesday, 3.29.05, 9:40 pm; collapsable Kung Fu top hat.

There are all kinds of rumbles, ass-kickings, foot-crunchings and whatnot. The edge is in the inspired, cartoon-like lunacy of the visual imaginings, the choreography and the CGI. And also from the occasional surprise turn, like when a certain studly, good-looking warrior with a great fighting style gets his head sliced off like that…whoa.

There’s a great Roadrunner chase sequence between Sing and a fightin’, formidable character called The Landlady (Yuen Qiu)….surreal-funny, totally amped.

The final turn comes when Sing is hired by Brother Sum to break an all-powerful martial arts master called The Beast (Leung Siu-lung) out of some kind of insane asylum, and soon after realizes that he has a super-hero’s destiny. This revelation comes only at the very end, thus allowing Chow to do his dopey-ass comic stuff for most of the duration.

I asked Chow (and his interpreter, who stood next to him) if he was comfortable calling Kung Fu Hustle a martial-arts satire. “What’s a satire?” he asked.

I re-phrased by asking if Hustle is laughing at martial arts films, or laughing with them? Chow asked what the difference is. I said laughing at is basically about criticism and laughing with is about affection. “Definitely with,” he said.

Sony Pictures Classics chief Tom Bernard offering toast to Kung Fu Hustle star-writer-director Stephen Chow.

The schmoozing at the Palm eventually gave way to a sit-down dinner. Sony chief Tom Bernard dinged on his wine glass and offered a toast to Chow, and a few minutes later Ray director Taylor Hackford did the same, praising Chow for his wit and visual pizazz.

Critics and Asian cinema scholars David Chute and Andy Klein (writing now for L.A.’s City Beat) were there also, along with Movie City News editor/columnist David Poland and a few other journos. My thanks to publicists Melody Korenbrot and Ziggy Koslowski for inviting me.

I fell off my diet by eating filet mignon and lobster, but eating steak is okay by the Atkins Diet so I guess I didn’t screw up too badly.

Sydney’s World

There are classic chase scenes and classic suspense sequences, but it’s rare to come across a really superb two-in-one. I don’t know if this has gotten around, but such a sequence — and it’s a major wow, trust me — is in Sydney Pollack’s The Interpreter (Universal, 4.22).

At the same time, it’s too bad that Universal’s marketing department has spoiled the climax by including it in their Interpreter trailer.

I’ve provided the link because it’s a free country and we can’t ignore what Universal has done, but do yourself a favor and don’t watch it. If the trailer plays before a film you’re about to see over the next month or so, run out to the lobby…seriously.

Nicole Kidman (r.) in scene from Sydney Pollack’s The Interpreter (Universal, 4.22).

It’s standard practice for trailers to show the audience a clip of every “money” scene in a forthcoming film and therefore, in the case of thrillers, ruin 90% of the surprises. But the Interpreter giveaway is especially bad because of the unusual character of what’s being ruined.

This sequence doesn’t just get you on a visceral level — the finesse that went into the editing is truly dazzling.

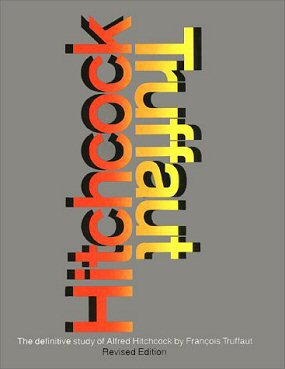

Let me explain by turning to a famous film lover’s book “Hitchcock Truffaut” (Random House), and an example of what makes a typically good suspense scene, as told by Alfred Hitchcock to Francois Truffaut.

A non-suspenseful approach, explains Hitch, would be to show a group of men eating in a restaurant when suddenly a bomb explodes and everyone is killed…shocking but that’s all. The suspenseful approach, he says, is to show the audience that a bomb is wrapped in a package under a restaurant table, and then tell them what time it will go off. Then a minute or so before detonation, have the men start to get up and leave but have one of them say, “Wait, I want to finish my coffee.”

Pollack and his editor, William Steinkamp, have taken a nervier approach in The Interpreter .

Instead of tipping the audience off about the certainty of coming destruction, they indicate that something bad is brewing…without revealing exactly what. They show various opposing forces (cops, bad guys, innocents) focusing on the same space or activity, and edit and score this scene so as to create a feeling of a fuse getting shorter and shorter and something about to pop.

Certain people are watching others, some are oblivious to anything but their own moves, some are playing their end of the court but are unaware of the overall, and so on. And it builds and builds and then…

Just don’t watch the trailer.

I have thought this through and I am showing restraint in comparing this scene to the Popeye Doyle subway car chase scene in William Freidkin’s The French Connection. The tension penetrates just as deeply, the editing is just as assured…it’s a marvel.

And on top of the sheer mechanics of this scene, it flashes the viewer into real-life associations that stay with you — I shouldn’t be any more specific.

The film itself is about as smart and satisfying as a mainstream political thriller can get. It doesn’t just push buttons — it delivers a compassionate theme and uses that familiar Pollack element of a love affair that might happen or work out…but it’s not in the cards.

This may sound like trivial terminology, but a screenwriter friend is calling The Interpreter “the ultimate over-25 date movie. There are no movies like this around right now that my wife and I like to go to together.”

Sean Penn

A friend is telling me Penn is too gnarly and internally bothered to succeed in a leading man mode. I think he’s blind. Penn’s innate ability to suggest a feeling of having suffered emotional wounds is precisely what makes his Interpreter performance work as well as it does.

Perhaps my friend is forgetting that Penn had an emotional breakthrough in 21 Grams. With audiences, I mean…it changed everything. It turned him into this decent hurting 40ish guy who smokes.

The careful strategic weaving of the dozens of story strands that have to fit together just so and pay off in the right way in a film of this sort (a discipline that Pollack used to fine effect in The Firm and Three Days of the Condor) is damned near immaculate.

And the performances by Nicole Kidman and especially Penn (bringing a certain grit and gravitas to what might have seemed like a fairly standard romantic lead role with someone else playing it) are ripe and impassioned and true to the mark.

Theory

I don’t mean to offend anyone or sound too clunky in my thinking, but I’ve always thought people who frequently go to serious action movies (as opposed to an off-the-ground variation like Kung Fu Hustle) are expressing feelings of social impotence.

The swift, decisive, lethal moves of on-screen combatants give the disenfranchised, pushed-around male masses a temporary feeling of spiritual strength and assurance, or so goes the theory.

Which explains, obviously, why they’re so popular with young males, the most impotent group in any society.

A scene from Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon.

It follows that in the case of hardcore fans, the more outlandish the action the greater the feelings of powerlessness.

Before anyone gets angry they should know I’m including myself in this equation. I got a definite charge from watching Tom Cruise blowing all those guys away with stylish dispatch in Collateral. But what his “Vincent” character did was in the realm of reality, or at least one that I accepted as being vaguely tethered to it.

It can be said that the widespread popularity of martial arts films in Asia, which are known for their flights into total cartoon fantasy of flying super-heroes with endless reserves of energy….it can be said that their popularity shows that feelings of social impotency run far deeper in Asia than they do here.

This is hardly a new observation, but how about some reactions?

Kid Flicks

“I loved your article about cultivating young cinema lovers. As a father of two young children — Bain, 5, and Lillie, 3 — I find myself in the same position of making sure my children grew up to not only good people but also appreciating good art.

“I’ve found that along with many of the films that you and Jett mentioned my kids will also watch silent films with me. Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton films are really popular around here, but my son also really liked Metropolis and The Cabinet of Dr. Calagari.

“Other non-animated favorites are John Boorman’s Excaliber, The Adventures of Robin Hood, any Tim Burton movie (except the totally forbidden Planet of the Apes) and Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast.

“For a long time my son would watch Dr. Strangelove over and over, referring to it as the ‘airplane Movie.’ I seriously doubt that the themes of the film were apparent to him, but somehow I think that hearing Sterling Hayden’s ‘purity of essence’ speech may have made an impression.” — unnamed husband of Karen McKibben.

“I definitely identify with your article on kids and movies. I have two young children, and I end up censoring what they watch over quality issues much more than content issues…although I’m sure at six years old my son doesn’t understand why Superbabies 2 isn’t worth the rental fee.

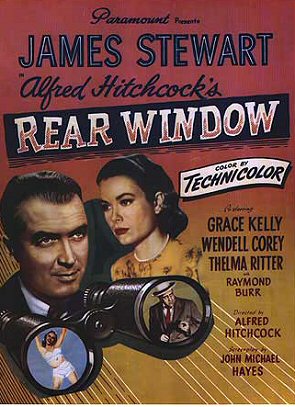

“It has paid off from time to time, though. A few months ago my hyperactive five year-old daughter sat perfectly still for two hours while we watched Rear Window, and she has asked to watch it again several times since. To be honest, I get a little choked up when I hear her give out a conspiratorial chuckle over what’s buried in the flower garden.” — Randall Pullen

“I saw Taxi Driver with my mom in Mexico City when I was twelve, and it changed me. I didn’t quite understand everything but it opened my eyes to a new kind of filmmaking. I don’t think your idea is bizarre. Bad movies teach youngsters that the world is black and white place where good and evil are easily identifiable and definable things. i think good movies show the world as complex and often baffling, where we all have the capability of being either good or bad, often on the same day.” — Tom Engel.

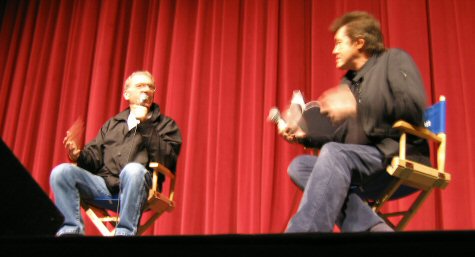

Pollack at UCLA

Sydney Pollack (l.) addressing UCLA Sneak Preview class after showing of The Interpreter — Monday, 3.28.05, 9:55 pm.