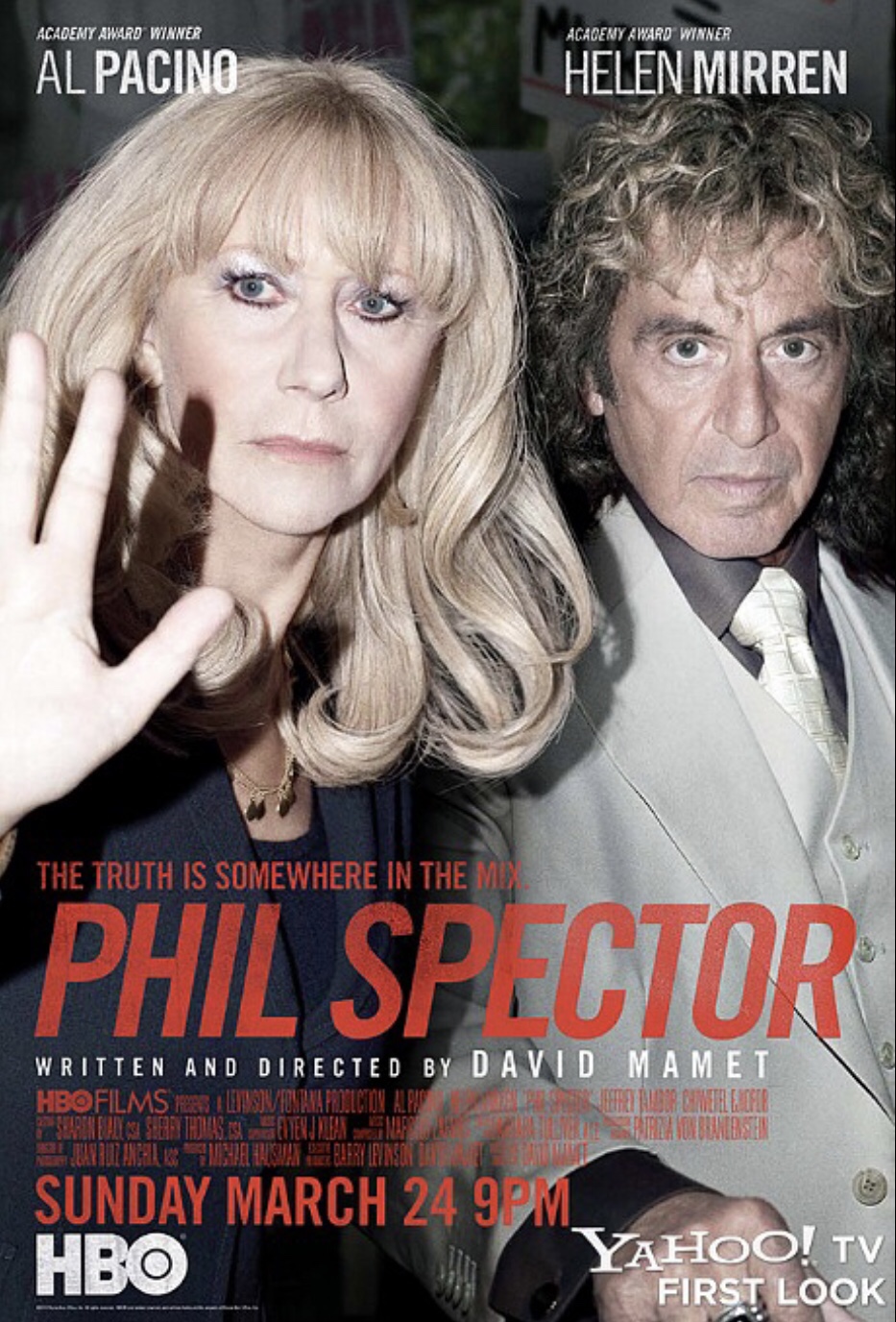

Phil Spector, the once-great music producer and guilty-as-charged murderer of Lana Clarkson, is dead of Covid at age 81. In a prison hospital, but basically in prison. Convicted of Clarkson’s ’03 murder in ’09, Spector would have been eligible for parole in 2024.

Most of the obits are going to repeat the standard line about Spector having been a brute and a fiend — an appropriate description, yes, for anyone who maliciously ends the life of another human being outside of armed combat.

But we’re all a blend of good and not-so-good elements, angels and goblins and all kinds of in-between, and I’m sorry but Spector wasn’t all fiend. (Just ask Greta Gerwig, who once told me she’s a big fan of Spector’s classic-era music.) Because for a certain period in his life, despite the fact that he was regarded as a bizarre permutation and an aloof prick by nearly everyone for decades…for a certain period he was touched by God. Or was God’s conduit…whichever.

Spector was the first maestro-level rock music producer, the creator of the famous “wall of sound” jukebox signature that peaked between 1960 and ’64, and was occasionally imitated by Brian Wilson and several others (Spector co–produced George Harrison‘s All Things Must Pass) for years following — “Be My Baby”, “Chapel of Love”, “Just Once in My Life”, “There’s No Other (Like My Baby)”, “Then He Kissed Me”, “Talk to Me”, “Why Don’t They Let Us Fall in Love”, “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin'”, “Da Doo Ron Ron”, “I Can Hear Music”, and “This Could Be the Night”.

Please, please watch Vikram Jayanti‘s The Agony and Ecstasy of Phil Spector, which has been on YouTube for nearly a decade. I wish it could be seen in HD. I would buy a copy if it was. It’s one of the best documentaries about a music industry superstar ever made — perhaps the best ever.

Here’s a piece I wrote about it on 6.28.10 — “Dark Star“:

I’m into Spector more than most people in my realm. Jayanti’s doc is what got me there. I’ve known Spector’s musical signature all my life — that “wall of sound” thing that gave such ecstatic echo-phonic oomph to all those early to mid ’60s hits (“Be My Baby”, “Walkin In The Rain“, “River Deep, Mountain High”) and Beatle songs he produced a few years later. But I’d never heard Spector speak or gotten to “know” him until I saw Jayanti’s doc.

Spector is a fascinating man — there’s no getting around that. A brilliant, oddball X-factor “character” of the first order. I’ve known a few guys like Spector. They’re egotists and half-crazy and it’s always about them, but they’re a trip to talk to and share stories with. If you love show business, you can’t help but love how these guys are always sharp as a tack and don’t miss a trick and are always blah-blahing about their genius and their importance.

Except Spector’s blah is backed up by truth. He really did shape and inspire rock ‘n’ roll in its infancy, and touched heaven a few times in the process.

Yes, he probably shot Clarkson, a 40 year-old, financially struggling actress, on 2.3.03 when she was visiting his home. Or maybe he threatened to shoot her and the gun accidentally went off. Or whatever. And maybe Spector telling a Daily Telegraph reporter two months before the shooting that “he had bipolar disorder and that he considered himself ‘relatively insane'” was a factor. And maybe he deserves to be in jail for 19 years. The guy is obviously immodest and intemperate with demons galore.

But you can tell from listening to Spector that he’s some kind of bent genius — that he’s brilliant, exceptional, perceptive — and that it’s a monumental tragedy that these qualities co-exist alongside so much weirdness inside the man — all kinds of strutting-egoist behavior and his having threatened women with guns and all of that “leave me alone because I’m very special” hiding-behind-bodyguards crap. Because life is short and the kind of vision and talent that Spector has (or at least had) is incredibly rare and world-class.

That’s why Jayanti’s film is so absorbing, and why the title is exactly right. Why do so many gifted people always seem to be susceptible to baser impulses? Why do they allow bizarre psychological currents to influence their lives? What kind of a malignant asshole waves guns around in the first place?

I’ll tell you what kind of guy does that. A guy who never got over hurtful traumatic stuff that happened in his childhood (like his father committing suicide), and who decided early on that he wouldn’t deal with it, and so it metastasized.

It’s another tragedy that this BBC doc, originally aired in England in 2008, is only viewable on YouTube, and in such cruddy (480p) condition.

Spector’s story encompasses so much and connects to so many musical echoes and currents that people (okay, older people) carry around inside, and the way this history keeps colliding with what Spector probably did (despite his earnest claims to Jayanti that he’s innocent) and the Court TV footage and the evidence against him and the thought of a woman’s life being snuffed out…it’s just shattering.

Phil Spector and the Ronettes during a 1963 Gold Star recording session in Los Angeles.

I’ve seen Jayanti’s doc twice now and I could probably go another couple of times. Anyone who cares about ’60s pop music and understands Spector’s importance in the scheme of that decade needs to see this thing. It’s a touchstone trip and an extreme lesson about how good and evil things can exist in people at the same time.

90% of the doc alternates between interviews with the hermetic Spector, taped between his first and second murder trials, and the Court TV footage. But the arguments and testimony are often pushed aside on the soundtrack by the hits that Spector produced with the Ronettes, the Righteous Brothers, Ike and Tina Turner, the Crystals, Darlene Love, John Lennon, George Harrison, Bob B. Soxx and the Blue Jeans (that rendition they and Spector recorded of “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” in ’63). It’s the constant back and forth of beauty and darkness, beauty and rage, beauty and warped emotion — repeated over and over and over.

I never knew that the title of Spector’s “To Know Him Is To Love Him” (which he wrote and performed with the Teddy Bears in ’58) was taken from his father’s gravestone. I’d forgottten that he wrote “Spanish Harlem” — an exceptionally soulful ballad for the 1960 pop market. I never gave much thought to what “Da Doo Ron Ron” meant — I never thought it meant anything in particular — but Spector says it’s a metaphor for slurpy kisses and handjobs and fingerings at the end of a teenage date. Spector also had a good deal to do, he says, with the writing of Lennon’s “Woman Is Nigger of the World.”

There are two curious wrongos. Spector mentions that his father committed suicide when he was “five or six” — he was actually nine when that happened. (How could he not be clear on that?) Spector also mentions that line about John Lennon having thanked him for “keeping rock ‘n’ roll alive for the two years when Elvis went into the Army” when in fact Spector’s big period began just after Elvis got out of the Army, starting around ’60 or thereabouts.

Spector mentions that if people like you they don’t say bad things about you, but it’s clear that if he hadn’t been such a hermit and hadn’t acted like a dick for so many years, and if he hadn’t been photographed with that ridiculous finger-in-the-wall-socket electric hairdo, and if he’d just gotten out and charmed people the way he does in the interview footage with Jayanti then…well, who knows? Maybe things might have turned out differently.