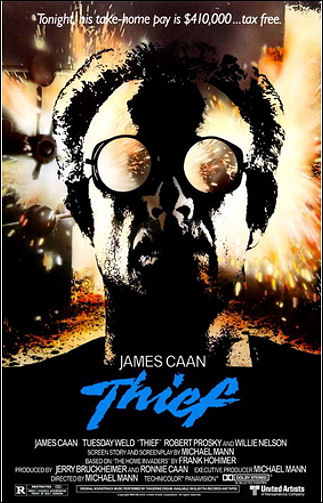

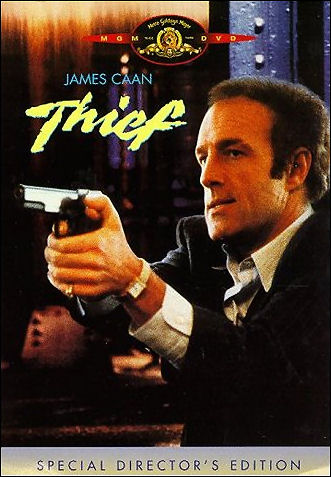

The late-night diner scene in Michael Mann‘s Thief — the best 9 minutes and 55 seconds that James Caan ever delivered, bar none. I found this clip after reading a 2.9.09 essay about this landmark 1981 film by KirbyDots’ Tristan Eldritch. Read it, watch the clip, and then start holding your breath while waiting for a Blu-ray version to appear. The last Thief DVD, released more than ten years ago, was okay, nothing more.

“Thief concerns an accomplished safe-cracker and ex-convict named Frank,” Eldritch writes. “Working independently with a small crew of trusted friends, Frank is a highly successful jewel thief who operates both a bar and a used-car lot as fronts. In terms of character, Mann develops Frank as a brilliant case study in how people are conditioned and shackled by past experience. Frank has already been traumatized by his childhood, in state-run orphanages, but it is his years in prison which ultimately define his personality.

“While incarcerated, he developed as a survival technique the ability to attain at will a state of almost Zen-like self-negation; a condition of complete emotional dislocation which divests his life and personality of all meaning, but nevertheless renders him fearless and psychotic enough to survive in a harsh and violent environment.

“This is, in many respects, a more extreme version of the austere survival discipline Neil McCauley has adopted in Heat: ‘Do not become attached to anything that you can’t drop in thirty seconds flat, when you see the heat coming around the corner.’

“The other chief pivot of Frank’s character, also developed in prison, is the postcard sized photo collage he has made as a symbolical representation of his dream of a better life. Despite his obvious affinities with the world of criminality, and his obsessive dedication to his craft as a thief, Frank longs for a life of domestic tranquillity and security, and his collage depicts all the trappings of this ideal: wife, children, and leafy suburban house and garden.

“Frank’s collage encapsulates what is both sympathetic and unnerving about his character, in that it illustrates the sincerity of his desire for a better life, coupled with an almost sociopathic belief that an idea can be pursued in a single-minded fashion, with no recourse to the complexities and contingencies of real life. A fatal aspect of Frank’s individualism is that he sees the world unfailingly as an extension of his own will, and thus when he sets about attaining his domestic ideal, he does so with almost the same degree of mechanical simplicity with which he has assembled the collage.

“It is worth noting that as much as Mann’s films deal with characters that identify to a compulsive degree with their vocation or career, the characteristic malaise of a Mann protagonist is actually the longing to escape that vocation.

“Frank has been dating a down-to-earth waitress named Jessie (Tuesday Weld), and plans to marry her and have children. He has promised that his criminal career will shortly come to an end, believing himself, in the archetypal style of so many sympathetic criminals in noir thrillers, to be a couple of big scores away from retirement. In his haste to actualise this retirement dream, he reluctantly starts working for a gangster called Leo. Thereby the chief momentum of the plot kicks in, predicated on Frank simultaneously setting up a big score for Leo, and organising his future life with Jessie.

“The problem, however, is that Frank’s life, both domestically and professionally, becomes increasingly and inextricably bound up with Leo. When Frank and Jessie are unable to adopt a child, Leo intervenes and provides a mother who is prepared to sell them her child. Meanwhile, Frank discovers that working for Leo has brought him to the attention of the police, who demand a cut of the take from the robbery.

“In some respects, Thief could be read as an extreme parable about the struggle between individualism and society. It’s Frank’s desire to lead an ordinary, family-based life which leads to his Mephistophelian pact with Leo, and the beginning of the complete erosion of his status as an independent, self-governing operator.

“The deal with Leo is a kind of extreme version of a social contract; Frank gets a home and a family, but with them comes a boss, and a fatal entanglement within a corrupt system of bribes and mutual favors; the system, according to both criminals and cops, of ‘how things are done.’ Leo changes from being a kindly and paternal figure to one of pure malevolence, asserting aggressively that he ‘owns’ Frank. Frank, in turn, realizing finally that he cannot achieve his dream on his own terms, falls back on the mental habits he acquired in prison. He dispassionately disassembles his long cherished dream, piece by piece, in an extraordinary eruption of sustained, cathartic violence. He cuts Jessie and their child completely from his life, sets fire to his businesses, and kills Leo.

“The question remains, however, after Frank has vanished into the dark horizon of the film’s denouncement, to what extent Mann intends Frank’s complete lack of compromise to represent a heroic apotheosis, or the self-defeating actions of a character that is psychologically damaged by his past.”

In my head, the movie delivers both themes simultaneously. The superficial, easy-to-roll-with interpretation is that Caan’s Frank is one of the ultimate hardcase movie badasses of all time. The deeper, ground-level read is that he’s an impossible purist whose bruised psychology has made him incapable of working with ‘the way things are done’ and therefore a tragic figure from the get-go. This fatalistic, fuck-all element is one reason why women have never liked this film (Pauline Kael raked it over the coals) and why it’s one of the all-time great guy films. You either get the take-it-or-leave-it duality or you don’t.