In recognition of tomorrow’s (4.27) DVD release of Sidney Lumet and Tennessee Williams‘ The Fugitive Kind, or more precisely the Criterion Collection’s rendering, an appreciation by David Thomson currently sits on the Criterion site.

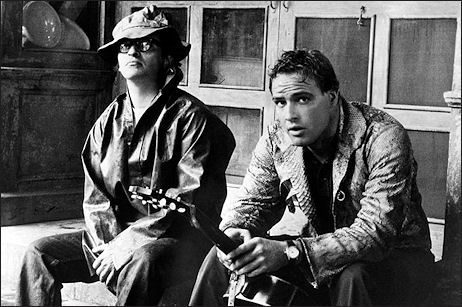

Sidney Lumet, Marlon Brando on the set of The Fugitive Kind.

“Movies are not just the sum of the stories that can be told about their shooting,” Thomson says toward the end. “The Fugitive Kind was unlike other films, and it was something Lumet had never tried before: a portrait of small-town meanness in which the outward action was to be fired by internal demons.

“In that sense, it was not too far from the wasteland of Psycho, which was filmed at the same time. Is Psycho a crime story from local papers (like In Cold Blood) or is it a movie that stirs at dysfunction in America? In the same spirit, The Fugitive Kind is true to the stark paranoia in Williams, minus the lush color and starry glory that marked the films of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Sweet Bird of Youth. Those hit movies look so much less now than Streetcar, Baby Doll and The Fugitive Kind.

“This is a mood picture, where, if you pay close attention, you can feel the lights come up and fade away to match the eloquence of the speeches. You can see the decor giving an emotional or spiritual force to the text. And you begin to hear Marlon Brando‘s shy lyricism rising in the long speeches — this Orpheus in a snakeskin jacket sings. Joanne Woodward gives one of the least guarded performances of her odd career. And Anna Magnani looks like a great sensualist terrified of getting her last chance.

“There’s no question that Magnani could do too much, but Lumet restrains her here and urges his cameraman to trust her tragic face and wounded voice. It was not often in this era that an actress shared the screen with Brando — so many were erased by his light. Lumet began by using markedly different lenses on the two leads, but as the film progressed, he let Magnani have more and more long-lens close-ups to match Brando’s. And so we feel their relationship growing in the most natural way.

“No one went to see the movie in 1960. It got no nominations at Oscar time. It lost a fortune. But it may be one of the most intriguing Tennessee Williams pictures, in that we are asked to weigh and consider the faults of its provincial society. It is about time we yielded our trust in box office, the Academy, and journalistic critics as measures of quality. We have to see the pictures for ourselves. In which case, it’s natural enough to notice that The Fugitive Kind is only two films before Lumet’s Long Day’s Journey into Night, another study of the light fading in a small town.”