I’ve been waiting to see Gerald Peary and Amy Geller‘s For The Love of Movies: A History of American Film Criticism for a long time. It’s been in the works for years. So many, in fact, that one of the talking heads appears as a young, lean-faced guy with a shock of dark hair (in footage that was shot around 2000) and as an older, fuller-faced guy with less hair. Happens to all of us, but this may be a first. Same interview subject, two biological incarnations.

Anyway, For The Love of Movies — directed and written by Peary, produced by Geller — is finally here and it does the job nicely. Which is to say intelligently, competently, lovingly and, after a fashion, comprehensively. Meaning that it tells the story as thoroughly as the budget and running time have allowed. For those who don’t know much about the lore of the realm, it’s nutritious food and then some.

It’s a hell of a subject — a chronicle of magnificent obsessions and magnificent dreams, and a rise-and-fall story covering scores of critics, the entirety of the Hollywood film culture from the ’20s to the present, and hundreds if not thousands of movies.

Ideally (and this is no slag on Peary or Geller) For The Love of Movies should have been a well-funded, six-part American Experience series on PBS, shot on 35mm by Emmanuel Lubezski, and including a vast smorgasbord of film clips donated by their copyright owners as a gesture of thankfulness. (Today’s production and marketing community may resent critics, but they owe them big-time.)

But Peary and Geller’s low-budget, hand-to-mouth approach will do for now. I’m very glad it was made, glad that I saw it. I hope others follow suit when it has its big debut on Monday, 3.16, at South by Southwest, and more particularly at the Alamo Ritz at 8 pm. And then on Wednesday, 3.18 at the same venue. And again on Saturday, 3.21, at the Alamo Lamar 3 at 4 pm.

Gerald Peary (l.) and Amy Geller (r.) with unknown female.

You can’t watch this film and not acknowledge that Peary and Geller are fully up to the task of providing a clean and cogent history lesson. Could they have made a snarkier, trippier excursion piece? A more poetic and probing cultural epic or tone poem…whatever? Yeah, probably, but they were budgetarily constrained and wanted to reach the not-very-hip (or moderately hip) crowd.

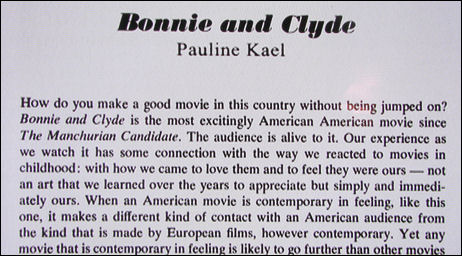

So they’ve thrown together an easy-to-digest, chapter-by-chapter saga of the last 90 years of American film criticism, starting in the mid-to-late teens with the emergence of Frank E. Wood, the first “cricket” to earn his stripes by investing a modicum of personal passion and a writerly point-of-view, and hiking all the way through Vachel Lindsay, Robert Sherwood, the great seminal trio of Otis Ferguson, James Agee and Manny Farber, the 20-year reign of Bosley Crowther, the fall of Crowther over his Bonnie and Clyde review, the influence of Cahiers du Cinema and the auteur theory, the resultant reign of Andrew Sarris and The American Cinema, the huge influence of Pauline Kael and the writings of Stanley Kaufman, Vincent Canby, Richard Corliss, Richard Schickel, Molly Haskell, Roger Ebert, Stuart Klawans, etc.

This feels like Billy Joel’s “We Didn’t Stop the Fire.” I’m hearing a film-critic spoof version of the lyrics. Come to think, a mock music-video interlude would have been a great thing for Perry and Geller to run with — seriously.

Gleiberman, Hoberman, Harlan tell-it Jacobson.

John Powers, Elvis Mitchell, Leonard Maltin, mumblecore.

Titanic, Janet Maslin, Wesley Morris, David Sterritt.

Ain’t-It-Cool, Rex Reed, Nesselson and junket whores.

Lisa Schwarzbaum, Orson Kane, Indies in the ’90s.

Wilmington, Weinberg, Siskel and Szymanski.

Ruby Rich, Kenny T., tits and zits, Anthology Film Archives.

I’ve lost the rhythm, can’t get it right, haven’t the time. Anyone?

For whatever reason Perry and Geller don’t mention the great French critic Andre Bazin. (Or at least not that I remember. He’s not listed in this cast roster.) Nor do they mention John Simon, whom I always regarded as a brilliant (if occasionally cruel) critic and one of the major go-to guys of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. Or Todd McCarthy, Dwight McDonald, Bertrand Tavernier, Andy Klein, Armond White, Ty Burr, Glenn Kenny, Anthony Lane, Scott Foundas, etc.

There are a lot of holes and gaps — let’s face it. The doc only runs 80 minutes. A longer length (115 or 120 minutes, say) would have obviously allowed for a more comprehensive summary.

For those who know a lot about the American film-critic monastery, For the Love of Movies is a tidy and agreeable canoe ride down memory creek. With a tinge of melancholy, I should add, although this comes more from my own feelings.

Peary and Geller, to put a point on it, have chosen not to emphasize the dominant reality facing established film critics in the 21st Century — i.e., the extinction of the monk-like film critic cabal as it was known and defined from the late 1930s and ’40s to the beginning of this century, and the drop-by-drop decline and diminishment of the power and prestige of the traditional film critic. Which is due, obviously, to the winding down of the Gutenberg era, blah blah. With some critics and columnists adapting to the new technological climate (ahem) and some not so much.

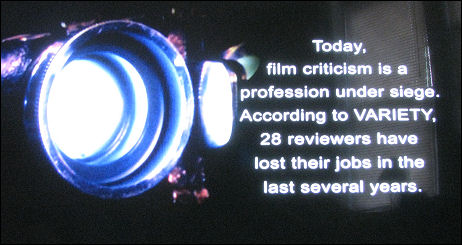

Peary and Geller acknowledge that it’s currently a sink-or-swim, do-or-die reality out there. They begin by saying that “film criticism is a profession under siege” and that “according to Variety 28 film critics have lost their jobs in the last several years.” That, of course, is dated information and isn’t the half of it. Sean P. Means‘ disappearing film critic list is currently at 49. MCN’s Last Film Critics in America list has the names of 121 who are still collecting a check.

Clearly we’re looking at the end of the road here, certainly for the elite culture portrayed in the film.

The prime kiss-of-death factor is a diminished interest among today’s tweeting, texting, 24/7 digital-feed generation in being passive recipients of the views of learned, brahmin-like, know-it-all film critics dispensing ivory-tower insights. Economic issues aside, the firing of film critics is rooted in today’s common-currency belief that everyone and anyone with a computer or hand-held device knows as much as those snooty-ass critics do. Or certainly that their opinion is just as valid, and that they prefer a more democratic, interactive bloggy-blog conversation as the dominant mode of dissection and discussion.

In short, there’s a whole current of lament than runs underneath this story that probably should have been explored with more frankness and feeling.

For The Love of Movies is narrated by Patricia Clarkson. I don’t want to be a crank, but I would have preferred to hear a raspy, whiskey-tinged male voice tell the tale. The voice of someone who sounds like he might have personally lived through some of the history. Michael Wilmington would have worked in this respect.