Truman Show

I’ve seen Bennett Miller’s Capote (Sony Classics, 9.30) twice now, and I’m afraid I’ve got it bad. I love this film…so much that my reasons for feeling this way are a bit more personal than usual.

Why get into it now, a little more than four weeks before it opens? Because I’m in Toronto and for me, the festival has begun (advance screenings are happening left and right for local press), and because everyone will be giving Capote pats on the back once the festival starts on 9.9 so I might as well pat first.

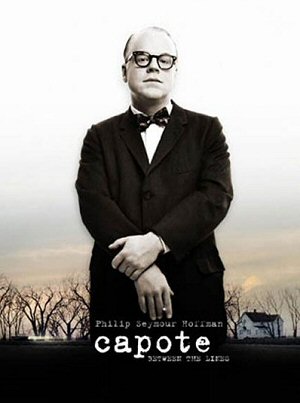

Phillip Seymour Hoffman as the conflicted, terrier-like Truman Capote in Bennett Miller’s Capote (Sony Classics, 9.30)

I’m taken with Capote partly because it’s about a writer (Truman Capote) and the sometimes horrendously difficult process that goes into creating a first-rate piece of writing, and especially the various seductions and deceptions that all writers need to administer with skill and finesse to get a source to really cough up.

And it’s about how this gamesmanship sometimes leads to emotional conflict and self-doubt and yet, when it pays off, a sense of tremendous satisfaction and even tranquility. I’ve been down this road, and it’s not for the faint of heart.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

But I’m also convinced that Capote is exceptional on its own terms. It’s one of the two or three best films of the year so far — entertaining and also fascinating, quiet and low-key but never boring and frequently riveting, economical but fully stated, and wonderfully confident and relaxed in its own skin.

And it delivers, in Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s performance as Capote, one of the most affecting emotional rides I’ve taken in this or any other year…a ride that’s full of undercurrents and feelings that are almost always in conflict (and which reveal conflict within Capote-the-character), and is about hurting this way and also that way and how these different woundings combine in Truman Capote to form a kind of perfect emotional storm.

It’s finally about a writer initially playing the game but eventually the game turning around and playing him.

Hoffman is right at the top of my list right now — he’s the guy to beat in the Best Actor category. Anyone who’s seen Capote and says he’s not in this position is averse to calling a spade a spade.

I’m not talking about Hoffman doing a first-rate impression of a famously effeminate celebrity author of the ’60s and ’70s. I’m speaking of his ability to make us feel the presence of Capote’s extraordinary talent and sensitivity and arrogance…a self-amused cocky quality born of extraordinary smarts and a feisty temperament that could suddenly veer into aloofness or even cruelty and at other times devolve into childlike vulnerability.

There’s always a sense of at least two and sometimes three or four rivers running through this character at once, all of it vibrating and churning around in Hoffman’s liquidy eyes and, when things get especially difficult, his nearly trembling pinkish- white face, and in the way he walks and gestures and shrieks with laughter at parties, and in the way he occasionally just stands utterly still. It’s an astonishing piece of work.

A friend thinks Hoffman isn’t small enough to play Capote, who was about 5′ 2″. Other naysayers may be heard. There’s a tradition of straight actors portraying flamboyant queens (I’m thinking way back to Cliff Gorman’s performance in William Freidkin’s The Boys in the Band) that hasn’t dated all that well, but Hoffman is doing so much more in this film that the comparison isn’t worth mentioning.

I can’t stop re-running my favorite parts of Hoffman’s performance. There are so many lines and moments, but to describe them would only muck it up. Maybe later…

Truman Capote, Kansas Bureau of Investigation chief Alvin Dewey, and Dewey’s wife Marie in ’60 or ’61.

Capote is fundamentally about “In Cold Blood,” Capote’s groundbreaking non-fiction novel that came out in early ’66.

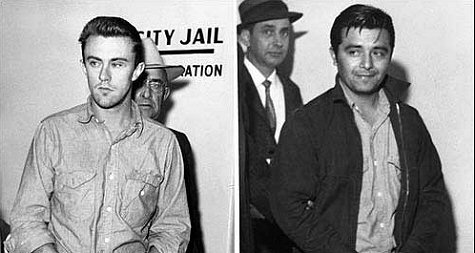

The book was about the murder of the four members of the Clutter family of Holcomb, Kansas, and their killers, Dick Hickock (Mark Pellegrino) and Perry Smith (Clifton Collins, Jr.). The film is about Capote’s researching and writing of the book, a process that lasted from November 1959 until the summer of ’65, and which pretty much tore Capote to shreds.

The core material has to do with a kind of love affair that happened between Capote and Smith during the death-row interviews conducted by Capote from the time of the murderers’ conviction in early 1960 until the hangings of Smith and Hickock in April ’65. Capote fell in love with Smith because they had shared similar traumatic upbringings (alcoholic mothers, family suicides) and because Smith had certain poetic-artistic aspirations.

“It’s like we grew up in the same house, except one day Perry went out the back door and I went out the front,” Capote tells his longtime friend and confidante Nelle Harper Lee (Catherine Keener), the author of “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

He really feels for Smith…you can see it, feel it…but Capote is scrutinizing enough to step back at every juncture and eyeball his relationship with Smith in literary terms. After persuading Smith to let him read his diaries, Capote tells Lee that this sad, doomed, hugely conflicted man is “a gold mine.”

The fascination is in watching Capote play Smith like a pro while getting more and more caught up with him emotionally. He gets the two killers an attorney following their conviction so he can get their execution delayed so he can get their full story. And then he lies to Smith time and again.

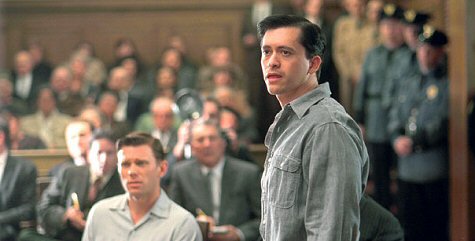

Mark Pellegrino (left, seated) as Dick Hickock and Clifton Collins, Jr., as Perry Smith in Capote.

The real Hickock and Smith, upon their arrival in Kansas in early January after being arrested in Las Vegas, Nevada.

And after he’s gotten most of their story he begins to acknowledge that he wants them executed so his book will have a finale, even though his feelings for Smith have always been, as far as it goes, earnest.

There’s a nice scene when Capote tells Kansas Bureau of Investigation chief Alvin Dewey (Chris Cooper) that he’s decided to call his book “In Cold Blood,” and Dewey says, “Is that a reference to the crime, or the fact that you’re still talking to the killers?”

When their long-delayed death sentences are finally at hand, Capote’s feelings come to a boil. His last meeting with them, moments before the end, is choice. Tears flooding his eyes, Capote tells them both (but particularly Perry), “I did everything I could…I truly did.” Which was true, in a manner of speaking.

I never figured Bennett Miller would direct Capote quite so well. He’s never directed a feature and has mainly confined himself to TV commercials, although he directed a very fine 1998 documentary called The Cruise, a black-and-white portrait of the great Timothy “Speed” Levitch.

To me, Capote feels as controlled and precise, as emotionally on-target and penetrating as any film by Louis Malle. You could run it with Damage and Atlantic City at the Museum of Modern Art, and it would feel like the exact same guy calling the shots.

I was especially taken with Miller’s decision to shoot Capote in widescreen Panavision (2.35 to 1). Stories of this sort — internal, intimate, dialogue-driven — are usually shot in 1.85 to 1 (or on video). Was Miller thinking about creating some kind of visual relationship to Conrad Hall’s widescreen photography in Richard Brooks’ In Cold Blood, even though that 1967 film was shot in black and white?

And a sincere tip of the hat to screenwriter Dan Futterman, who worked on the screenplay for a long time before getting it right. It’s based on Gerald Clarke’s “Capote,” which is probably the best Capote biography.

Futterman has known Miller since they were twelve, and they’ve both known Hoffman since ’84 (i.e., the year Capote died of alcoholism) when they met at a summer theatre program in Saratoga Springs,

Every performance in Capote feels rooted and lived-in…nobody seems to be “acting” in the slightest.

Clifton Collins (previously best known as the gay Mexican assassin in Traffic) is as good as Hoffman. He plays it subdued and far less animated, but he lets you see into Smith’s tormented soul, and I didn’t think once about Robert Blake’s strong performance as Smith in the 1967 film.

Keener’s Lee is restrained and exacting and yet she’s fully “there.” And Cooper’s Dewey delivers just the right mix of gruff Midwestern conservatism and emotional suppleness. (He’s a tiny bit warmer than John Forsythe’s Dewey was in Brooks’ film.) Dewey’s wife Marie, a friendly and sophisticated soul, is warmly and agreeably captured by Amy Ryan. And I love Bob Balaban’s small but succinct performance as former New Yorker editor William Shawn, who was in Capote’s literary corner the whole time.

The lesser lights are Bruce Greenwood, as Capote’s significant other Jack Dunphy, who hasn’t much to say or do, and Mark Pellegrino’s Hickock, who isn’t nearly as emotional or gregarious as Scott Wilson was in the Brooks film, although he seems like more of a killer than Wilson did.

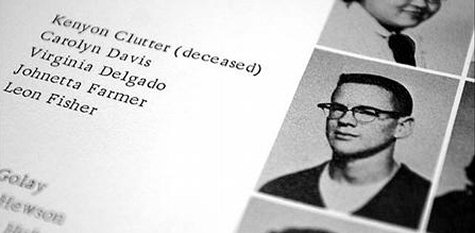

Gravesite in Garden City, Kansas — a mid-sized city to the east of Holcomb.

Photo in June 1960 high-school yearbook.

Capote may not sell as many tickets as Crash did, but it will be astonishing if people of taste or discernment don’t see it and tell their friends, etc. I realize that the number of people who read books, much less those who remember “In Cold Blood” or who remember Capote from his talk-show appearances, is relatively small. But if the word-of-mouth is good…

The challenge to Sony Pictures Classics is to keep the inevitable talk going into Oscar season and keep flogging it with the Academy.

After I send this column off today I’m paying a visit to a bookstore and buying “In Cold Blood” again. I haven’t read it since I wrote a book report about it in my senior year of high school.

Mafia Rules

I have this idea for a piece I’d like to run on Friday. I’m going to need write-in replies sent no later than midday Thursday.

The idea is, if Hollywood were run like the mythological mafia and you, the reader, were the boss of all the families with absolute control, whom in the Hollywood filmmaking game would you decide to whack for the good of the industry?

Not because they’re not nice people or aren’t skilled or have nice smiles, but whom would you eliminate in order to strengthen the industry and discourage bad tendencies, etc.? Remember that being the boss is a lonely job because somebody has to make the tough calls.

“I ask you, Don Corleone, please…spare Michael Bay.”

If I was Don Corleone of Hollywood and Hollywood was a real mafia society, I would put a general preemptive contract on anyone planning to make a film like Love Actually.

I would also put a contract, no offense, out on Johnny Knoxville. Somebody needs to pay for The Dukes of Hazzard, and Seann William Scott gets a temporary pass because he’s trying to redeem himself by making Southland Tales for Richard Kelly.

I would also take out Michael Wilson and Barbara Broccoli, the 007 producers.

I don’t think I need to say this, but I don’t believe in whacking people in the real world. I don’t even like stepping on bugs.

If I were an actual (i.e., actual mythological) mafia don I would build a secret private jailhouse — a maximum security prison out in some remote corner of the world — and then I would kidnap the guys who need to be whacked and send them to this jail, and they’d stay there with three hots and a cot until I died or got whacked myself.

My inspiration for this piece is Anthony Quinn’s Col. Andrea Stavros character in The Guns of Navarone.

David Niven, Gregory peck, Anthony Quinn in poster art for J. Lee Thompson’s The Guns of Navarone.

Quinn, Gregory Peck and David Niven are discussing the fate of Anthony Quayle’s Lucky character, who was broken his leg during a climb, and they’ve come up with two possible scenarios — take him with them on their mission to blow up the guns, or leave him to be found by the Germans.

And Quinn says, “There is, of course, a third option. One bullet now. Better for him, better for the mission.” Quinn is not playing a monster, just a hard-nosed commando.

And I’m channeling this spirit because, as Marlon Brando’s Colonel Kurtz would undoubtedly agree, doing the hard necessary thing is not always an act of kindness.

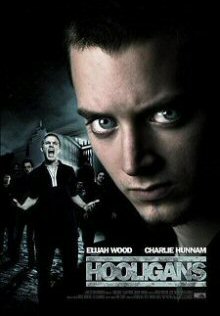

Hooligans

“After reading your take on Lexi Alexander’s Green Street Hooligans, I felt I had to give you a UK perspective on the movie. I watched what has been re-titled Green Street for UK audiences at a London preview last week.

“To me, and to most of the preview audience I saw the movie with, football hooliganism is old news. It was a hot button issue in the 1980s (when Alan Clarke’s The Firm was made) but since then most of the biggest firms have been busted.

“Thankfully, hooliganism has been mostly stamped out by no-tolerance policing, video surveillance at all games and better intelligence. It still exists, but it has gone underground.

“I grew up in a mainly working class neighborhood in a city called Portsmouth, on the south coast of England. Much like the movie, Portsmouth had a poor football club (although they’ve gotten a lot better) and an infamous firm of football hooligans (the 657 crew). Hooliganism was born out of a culture of binge drinking and violence.

“The idea forward by the movie that these firms only ever targeted their counterparts in rival firms is at best a simplification and at worst a glamorization of what they did.

“Often hooligans would simply pick off hapless away supporters who got lost in a strange city. If Pompey lost a match, hooligans would often run riot through the city vandalizing property and beating up any rival fans they could find, or failing that, anyone who wasn’t white.

“For a good drama about football hooligans, which exposes the hooligan’s links to British neo-nazi groups, I recommend I.D.’ (1995) directed by Philip Davis. I realize that the `stand by your friends whatever’ code that Green Street espouses is appealing, but please don’t confuse this with the mindless thuggery of real football hooliganism.

“I must also take issue with the way you characterize ‘this bizarre world of Brit football fanaticism.’ Football hooligans are not true football fans; they are in it for the violence. If you want a picture of Brit football fanaticism as opposed to hooliganism then check out the original version of Fever Pitch(1997), directed by David Evans.

“As for the movie itself, while the action sequences do have a real energy to them, the flat dialogue scenes in-between fatally hamstring the film. This is best illustrated by the opening scene in Harvard which, as you admit, `isn’t a very convincing beginning,’ and by the clunky scenes in which Matt Buckner (Elijah Wood) is tutored in cockney-rhyming slang. These scenes had the London preview audience chuckling and shaking their heads.

“The other problem is Elijah Wood’s inability to be convincing in his fight scenes. Although his character starts out as useless, after he becomes a seasoned member of the Green Street Elite he is supposed to have toughened up and learned to give and take a punch. However Wood continues to flail around in an embarrassing fashion in all his fight scenes, which may explain the director’s decision to shoot most of his fight in slo-mo (to try and disguise this).

“I agree that Charlie Hunnam is the real star of Green Street. He certainly makes the film watchable. I was surprised to learn that he is British though as I had assumed from the movie that he was Australian. His is a charismatic performance, but his London accent frequently slips into a bizarre almost Aussie accent. I guess your have to have lived in London for a few years in order to pick up on this, but I was wincing in places.

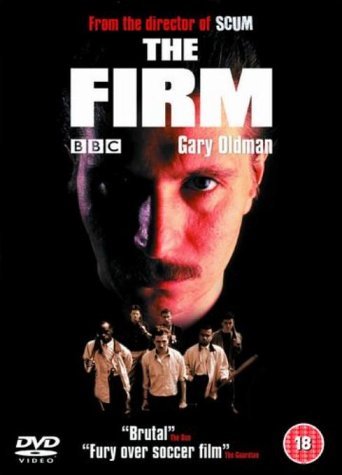

“Alan Clarke’s The Firm is a great film, which I strongly urge you to see. Like Scum it acknowledges the attraction that violence holds for some young men while simultaneously exposing the rotten culture that spawned it.” — Clive Ashenden

“Alan Clarke’s The Firm, which you mentioned in your piece about Green Stret hooligans, is a superb portrait of hooligan life (and probably more relevant, as the `80s were the pinnacles of English football hooliganism), featuring Gary Oldman’s best performance, before he took a liking for expensive scenery.

The U.S. release one-sheet (l.) and the British release version (r.)

“I’m not sure about the Green Street Hooligans flick. During the `70’s and `80s English hooligans were the worst — real scum who killed and maimed across Europe. Since all English clubs were banned following the Heysel tragedy, English football has come a long way, with a more family atmosphere at the grounds and less trouble at matches.

“For those who don’t recall, the Heysel disaster of May 29, 1985, led to the deaths of 39 fans and a five-year blanket ban on English clubs in European football.

“Juventus fans were given tickets adjacent to the Liverpool contingent who began by throwing stones and bottles, then charged the very thin blue line of under-equipped, poorly trained Belgian police. A section of Liverpool followers then stampeded towards the rival fans.

“A retaining wall separating the Liverpool followers from Juventus supporters in sector ‘Z’ collapsed under the pressure and many were crushed or trampled when panicking Juventus fans tried to escape.

“Thirty-nine Italian and Belgian fans died and hundreds were injured.

“I’ve been abroad and in the company of English hooligans. There isn’t a family/loyalty/ love equation going on. They use the cover of football support and rivalry to justify fighting with anyone and everyone who crosses their path. I’ve seen cars packed with holidaying families assaulted by `fans’ for the crime of hooting their horn.

“It’s just a booze-fueled, pack-animal mentality. Nothing more, nothing less.

The lads doing what they know, love and do best in Lexi Alexander’s Green Street Hooligans (Odd Lot, 9.9)

“Do we need another hooligan movie? I think not. No matter how hard any director tries, these films ultimately serve to sate those who wish to glorify and glamourize the worst side of our national sport.” — Dylan Glover, UK.

“The Firm, like a lot of Alan Clarke’s work, was commissioned by the BBC. This is when the Beeb wasn’t afraid to premier new, once-off dramas by Mike Leigh, Ken Loach et al. on a weekly basis and around the time when the broadcaster fell afoul of the establishment with its astonishing Sunday night drama one-two punch of Alan Bleasdale’s The Monocled Mutineer and Dennis Potter’s The Singing Detective.

“It’s been a long while since I saw the firm but Gary Oldman’s portrayal of the main protagonist, Bex, really made punters and critics sit up and take notice. Shot on video, there’s little overtly cinematic about The Firm but its status as a cautionary tale of the Thatcher era — moneyed-up working class males in a more feminist-minded era take to soccer hooliganism as proxy warfare — stands unchallenged.

“I recall that The Firm (never released theatrically) played well across ages and interests because it didn’t stint on the violence, its origins or its consequences. Leach/Loach repertory player, Lesley Manville, was also top notch as Bex’s wife. Oldman himself was profoundly influenced by Clarke when he made his directorial debut, The War Zone, and it’s just a shame he’s been unable to find a script of its ilk since them.” — Neil King.

Grabs

Bloor Street facing east, downtown Toronto — Wednesday, 9.1, 11:25 am.

Coming into Toronto on Continental Airlines — Tuesday, 8.30, 12:55 pm.

Adjacent to Metro North train platform in Bethel, Connecticut — Sunday, 8.28, 1:40 pm.

Lexington and 54th — Monday, 8.29, 6:50 pm.

Brill building lobby (reverse angle of shot that ran in last Friday’s column).

Has the ripple effect of the failure of The Island extended to the sales of “Island Puma” shoes that Ewan MacGregor and others wore in the film? I have no hard data to back this up, but I do know that Puma’s of this sort sell for $90 or $100 bucks, and yet these black-and-white Puma’s were being offered on sale last week on 14th Street…these plus another pair for $80.