Freshly Perverse

In anticipation of Neil LaBute‘s The Wicker Man (Warner Bros., 9.1), yesterday I rented a DVD of Robin Hardy‘s ’73 classic of the same name. (The extended version, of course.) Sharply written by playwright Anthony Shaffer (Sleuth), it has a reputation of being an exceptionally creepy piece. Which it is, although it contains only one big jaw-dropper at the finale. Which there’s no forgetting. And yet it’s far from a horror film.

Boiled down, Shaffer and Hardy’s Wicker Man is a correctly mannered, somewhat dry parlor drama with an undercurrent of female eroticism and faint malice. It’s pretty much all talk and inference, but in the service of something quite strange.

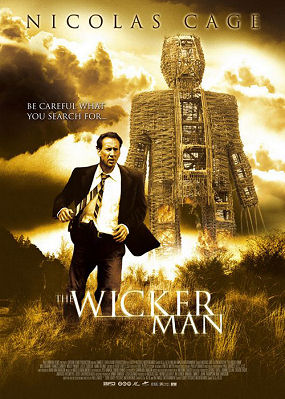

Nicolas Cage, director-writer Neil LaBute during filming of The Wicker Man (Warner Bros., 9.1)

It’s about a rigid, devout, clearly uptight Christian policeman (Edward Woodward) visiting a pagan society on an island off the Scottish coast in search of a missing girl, and his being constantly deceived by the locals in a strangely uniform way. Every last islander is either blank-faced or oddly cheerful, which seems especially weird in view of what they’re all planning. Lo, how righteousness spirals upward to the heavens, contained in a twisting plume.

The Wicker Man wouldn’t work nearly as well without the hammer-like energy and fierce conviction that Woodward brings to his role of Sgt. Howie. There’s no ques- tioning this cop’s intense Christian convictions — he’s all about discipline, rectitude and butt-plug righteousness. And, of course, sexual repression.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

What happens to Howie at the end is what The Wicker man is all about — a metaphor about the fast-eroding influence of traditional Christianity in the face of the newborn spiritual currents of the late ’60s and early ’70s (LSD mysticism, Bhagavad Gita, Tom Wolfe‘s “third great awakening”) and the general shirking of tradition.

What will the metaphor of the new Wicker Man be? Labute wrote the script (naturally), and one of his changes is that the remote island society is now matriarchal instead of patriarchal, as it was in the ’73 film. (In this light, Ellen Burstyn is the new Christopher Lee.) LaBute said at Comic-Con a couple of weeks ago that the film is at least partly about the fact that “women scare me more than men,” or words to that effect.

With men’s social dominance eroding over the last 35 or 40 years, their powers increasingly diluted and on the downswing and guys feeling less and less vital, it seems reasonable to assume that LaBute has made tthe growing stength and independence of women (and the way this has made some guys feel) the focus of his film.

What’s for sure is that LaBute hasn’t made a standard-issue Lionsgate shocker. More assaultive than the ’73 film, but relatively restrained by the standards of 21st Century jolts and gore. And however it turns out, something his and is alone.

In a piece by Charles Lyons in today’s , LaBute says, “Even if there are a few people who are pushing you in saying, `We would love it if this movie was Saw for the first weekend, and it was The Sixth Sense for the next five weeks, you ultimately have just one film that you can create.”

The Wicker Man “probably has a number of scenes that are bloodier than anything in the original,” Lyons reports, adding that LaBute “deliberately exercised restraint in using special effects that, as he put it, provide only a ‘moment’s pleasure.'”

LaBute’s film, says Lyons, “will echo its forebear’s intelligence, even if that means making the contemporary audience work a little harder than usual. ‘If The Wicker Man is a thinking person’s horror film,” says LaBute, ‘that’s great.'”

Like Sgt. Howie, Cage’s cop — called Edward Maulis in Labute’s film — is conservative-minded but more “suave” than Woodward’s character, or so Lyons reports.

This lewd and leering shot is from a scene always mentioned in any discussion of the ’73 Wicker Man — a musical number (yes, a musical number) featuring Britt Eklund, whose singing voice was dubbed by either Annie Ross or Rachel Verney.

One curious thing: Lyon’s article devotes five paragraphs to the fragile ego of Hardy, the original Wicker Man‘s director, specifically his conviction that he was slighted by the producers of the new version when they failed to show him a copy of LaBute’s script and/or declined to let him see the film. Five paragraphs out of 22 — more than 20% of the piece.

The point, I guess, isn’t that Hardy’s feelings are hurt as much as the Wicker Man team doesn’t want anyone knowing what they’re up to.

This seems to be so. The Warner Bros. marketing plan doesn’t seem to include letting guys like me see The Wicker Man early and possibly writing about it. I’ve been trying to get an early peek since early July, but the word all along has been, “We know that you’re a Labute fan but not yet…we’ll let you know.”