“Best Picture of the Year” means different things to different folks. For some (most, I suspect) it means being the most fundamentally “entertaining” — the one that will most likely reach the largest middlebrow audience. (Which is why a lot of people are suddenly behind Dreamgirls.) For others, it’s the film that’s the most soul-soothing or life-capturing (Volver, Babel, Little Miss Sunshine, The Lives of Others ). Or that seems the most complete and fully realized according to its own particular rules (The Departed, The Queen, Pan’s Labyrinth, United 93).

But for me, the highest synthesis of Best Picture satisfaction means delivering on one or two of the above plus one other — it has to be visually historic. It has to knock your socks off by way of sheer visual energy or innovation. So much so that what you’re seeing becomes absolutely “real” and everything else drops away. The popcorn is put under the seat, notions of bathroom breaks are out of the question, and you almost stop blinking for fear of missing something.

Alfonso Cuaron‘s Children of Men (Universal, 12.25) is that film, and is my choice so far for Best Picture of the Year.

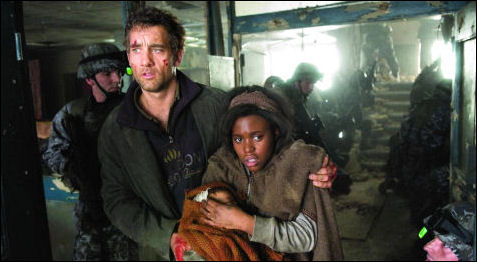

This is a futuristic, dystopian end-of-the-world actioner and grim as hell, but what mainly comes through is how remarkably convincing it all looks and feels. Set in 2027 England, It’s one of the most exactingly detailed, full-on visions of a totally-fucked future — a world in which women have stopped having babies — that I’ve seen in any medium ever. Jim Clay and Geoffrey Kirkland‘s production design is so precisely composed that it easily trumps whatever down-head feelings the film may temporarily impart.

And yet Children of Men doesn’t push the moody atmospheric gloom-vibe of films like Dark City, The Handmaid’s Tale, 12 Monkeys or Blade Runner. Based on a 1993 novel by P.D. James, an elderly British woman who mainly writes murder mysteries, it’s a movie with underlying heart and hope — a vision of an Apocalyptic ruin that also delivers warmth and frailty and compassion, and a vision of life that actually includes a future.

Understand this above all: Children of Men is the most excitingly photographed thing I’ve seen all year. It’s easily in the realm of Full Metal Jacket, Black Hawk Down and Saving Private Ryan, only more so. It’s basically one long take after another, but the standouts are three bravura sequences that each last four or five minutes (longer?) without a cut, and involve truly astonishing feats of sustained choreography and miraculous camera movement. This alone should trump any misgivings you may have about any other aspect (although there’s not much to beef about).

In short — it’s the photography, stupid. The dp is Emmanuel Lubezki and the camera operator was George Richmond. I don’t know who precisely did what but the hand-held lensing is the stuff of instant legend. If Stanley Kubrick were alive today he would absolutely drop to his knees.

Any film buff who doesn’t rush out and see this film at least twice (and drag along as many friends as possible both times) is a traitor to the cause. That’s all there is to it — see it or live in shame. There’s no third option.

Children of Men may not satisfy every sector of the audience (I talked to a white- haired guy after the big Thursday-night premiere who thought it was the worst thing he’s seen in years), or even a majority of the big-gun critics. Variety‘s Derek Elley, astonishingly, gave it a mezzo-mezzo review after catching it at the Venice Film Festival. And I’ve heard the usual beefs about Clive Owen not exuding enough warmth. And there is concern among Universal execs that Men may not make a whole lot of coin.

Children of Men director-co-writer Alfonso Cuaron (r.); the great Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki , the film’s dp, to the left

But ten, twenty or fifty years from now, long after the pure-fizz movies (the ones that sometimes make people giddy and chuckly when they’re first seen) have been forgotten, people who care about the eye-popping art and vitality of cinema at its finest will be watching Children of Men.

I guess that white-haired guy was brought down by Cuaron’s vision of a crumbling world — worldwide infertility, bands of terrorists, mass chaos, people in cages, roving criminals on every corner. Britain, however, is the last island of relative stability in this world of November 2027. All the other countries have collapsed into total ruin.

What rings so true about this polluted Orwellian atmosphere is that it’s not radically different from the England of today — it’s just a bit grimier and madder with more cops and bigger video-screen ads, and a lot more animals on the streets, and much dirtier exhaust coming out of everyone’s tail pipes. Soldiers and cops are roving all over the place, warnings are constantly broadcast and posted. Broken windows, rampant graffiti, kids throwing rocks and garbage at passing trains….all the signs.

The key plot point is that there have been no births in the world since 2009. It’s over — everyone has given up.

Cuaron, Ashitey, Owen during the Venice Film Festival

Owen’s arc is to go from being a bitter disllusioned milquetoast — a bureaucrat named Theo Faron who can only shuffle along and think of his own misery — to a fighting humanist-activist doing everything he can to protect an illegal refugee named Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey), who, we soon learn, is miraculously pregnant. If it lives, the baby inside her will be the first child on the planet in 18 years. And it falls to Theo to smuggle Kee to a group called the Human Project, a group of scientists trying to find a cure for global infertility.

Michael Caine plays the only joyful character, a former political cartoonist-turned- pothead named Jasper who’s also Theo’s best friend. He’s in only two scenes but nonetheless lifts the film’s spirit significantly. Peter Mullan adds another energy jolt toward the end as a half-crazed cop friend of Caine’s.

The action starts with Theo being kidnapped by an immigrant-rights terrorist group run by Julian (Julianne Moore), a former lover of Theo’s who gave birth to their child only to see it die. She wants Theo to get hold of transit papers for Kee, which he does. But then things start to go crazy, and soon the film is pretty much one chase or high-peril situation after another.

That’s another reason people may pigeonhole this film as being less than it is — they’ll say it’s just another futuristic action flick.

I don’t think it matters at all if Cuaron and Timothy J. Sexton, who share script credit, have dealt with the various issues with sufficient or insufficient detail. It didn’t bother me that the infertility thing is never really explained — what mattered to me is that I absolutely believed it had taken hold.

The photography is legendary not just for the excitement factor, but because it’s fascinating to try and figure out how this and that sequence was shot. My favorite is an attack on a car in the countryside — it’s a single take that reportedly required a special mini-crane that allowed the camera to shoot both inside and outside the car. The big battle sequence at the finale is mind-blowing. It’s basically the final battle sequence in Full Metal Jacket on steroids.

I had thought of Cuaron mainly as a soulful-whimsical dramatist after Y Tu Mama Tambien. His Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (’04) was better than the others, but I did what I could to ignore it. His short in Paris J’etaime (“Parc Mon- ceau”) was pretty good. Children of Men, however, is a huge leap forward. Now he’s one of the big-boy visionaries in the class of Kubrick, Orson Welles, Spiel- berg, Gregg Toland, Chris Nolan, Ridley Scott, et. al.