John Carney‘s Once, which I finally saw last night at 10:40 pm or thereabouts, is the Sundance heart & soul movie everyone’s talking about. And you don’t need to be an NYU film scholar to understand why. A kickaround, no-star Irish musical love story, Once has an ether-like spirit that anyone who’s truly been in love will recognize in a flash.

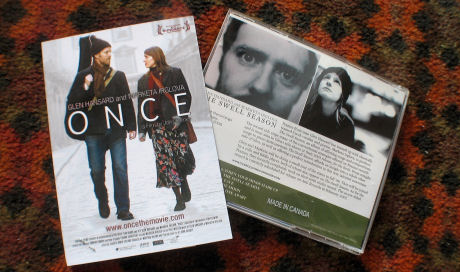

Once costars Marketa Irglova (l.), Glen Hansard (r.)

It’s about a pair of Dublin-based musicians — a scruffy, red-bearded troubadour (folk-rocker Glen Hansard, best known for his Irish group The Frames) and a young Czech immigrant mom (pianist and singer Marketa Irglova) — falling for each other by learning, singing and playing each other’s songs. That’s it…the all of it. And it’s more than enough.

It’s unique but gently lulling. It’s about struggle and want and uncertainty, but with a kind of easy Dublin glide-along attitude that makes it all go down easy. It’s all about spirit, songs and smiles, lots of guitar strumming, a sprinkling of hurt and sadness and disappointment and– this is atypical — no sex, and not even a glori- ous, Claude Lelouch-style kiss-and-hug at the finale. But it works at the end — it feels whole, together, self-levitated.

Carney’s decision to go with no-name actors (the early plan was for Cillian Murphy to play the troubador or “busker”) was risky; distributors are apparently concerned that Once isn’t commercial enough. That, ladies and gents, is the voice of timidity. Unless I’m crazy Once is going to win the Sundance Audience Award. (I could be wrong, of course, but the current in the Holiday Village theatre where it showed last night was quite palpable.)

Irglova, Hansard performing after last night’s screening of Once at the Holiday Cinemas — Monday, 1.22.06, 12:25 am

Trust me — there isn’t a woman or a soulful guy out there who won’t respond to Once if they can be persuaded to just watch it. The trick, obviously, is to make that happen, and I admit there may be some resistance. Initially. But once people sit back and let it in (and they’d have to be made of styrofoam for that not to hap- pen), the game will be more or less won. Settled, I mean. I don’t know if Once will make $5 million or $25 million or more or less, but it definitely has the stuff that people go to movies for.

Carney doesn’t give names to Hansard and Irglova’s characters, but it doesn’t matter. He sings songs to Dublin tourists for money while fixing vacuum cleaners for his dad’s shop; she, separated from her Czech husband and raising a small daughter with her mother, is a skilled pianist and singer who sells roses to tourists. And they seem like a match waiting to happen the moment they meet.

Things start off when she tells him she really likes a song he’s been singing, and also that she has a vacuum cleaner that needs fixing. The first big moment happens when he strums and sings one of his tunes in a music shop, and she quickly figures out harmony and piano accompaniment. Their next move is deciding to record an album together, which they manage to pay for (i.e., the studio rental) by finagling a $2000 loan from a bank. They get some street musicians to play accompaniment. The tracks turn out beautifully.

But Hansard is still hung up over a girlfriend who dumped him and moved to London, and he suddenly decides to go there also, mainly to pursue his music career but also to possibly rekindle things. And Irglova’s thinking the best thing for her daughter is to try again with her estranged husband. Will things work out between them regardless? Or is the musical connection enough, or even greater than the proverbial emotional and hormonal sparks?

During the post-screening q & a Carney called Once a musical in the tradition of Singin’ in the Rain, Carousel, Brigadoon and the like. It isn’t that, of course — it’s a groundbreaking musical in the vein of A Hard Day’s Night, Cabaret and Dancer in the Dark…a new kind of funky street musical with a fresh idea. A key component is that the film never seems to be pushing all that hard, which can be a huge plus in the right hands.

Hansard and Irglova’s characters obviously love each other for what they have in their hearts plus their ability to say this musically, and we get to absorb all this like flies on the wall. The tension is whether or not they can take things to the proverbial next level. Life is hard, love is harder…but music is all joy.

The sound was fucked and gurgly when the film first began to roll around 10:15, so Carney had it stopped and a team of tech-heads fiddled around and re-threaded the film. It started up again around 10:35 or 10:40 pm. It ran 88 minutes. Then Carney, Hansard and Irglova came up for a q & a, and then the musicians sang a beautiful tune heard a couple of times in the film called “Falling Slowly.”

Hansard and Irglova currently have an album out with all the songs from Once — it’s called “The Swell Season.” An official Once soundtrack CD will presumably be released later this year, concurrent with the theatrical release.

Note: I would have had this piece up this morning if it hadn’t been for the awful technical issue that occured around breakfast time — my apologies to all. And thanks to those who corrected my incorrect spelling of Hansard’s band — The Frames, not the Flames.