There’s nothing left to do now except sift through the last eleven and a half months for films to reconsider…maybe. The year is over, it’s settle-down time, screenings have stopped, and Christmas is only seven days away. So how about some lookin’ back, end-of-the-year love for the crazy-brave but titanically miscalculated Grindhouse, the three-hour exploitation double- feature flick that bombed so badly last April it just about sank the Weinstein Co.? It was a wank and a tank, but at least it was about an idea — a conceit — and it stuck to its guns.

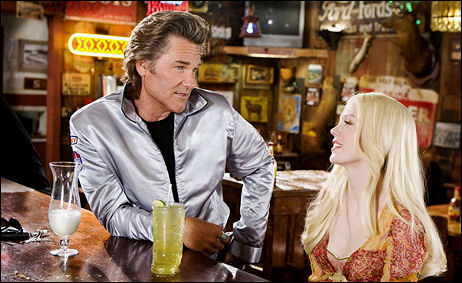

Kurt Russell, Rose McGowan in Quentin Tarantino’s

Death Proof There should at least be a a little retro affection for Death Proof, the Quentin Tarantino segment that delivered some of the tastiest, self-amused dialogue of the year, as well as one of the all-time greatest car-chase sequences…no?

I sat through a good portion of Death Proof the other day. (Not the shorter theatrical version, which is probably gone forever, but the longer, lap-dance version that came out on DVD last September.) There’s an art to making an agreeable waste of time — a film that totally skims the surface and brings absolutely nothing to the table of any consequence, but at the same time one that people half-enjoy because it has some nice moves and (this is essential) is 100% committed to its sense of swagger and is head-over-heels in love with itself because of this.

I love, love, love the Suntman Mike dialogue in the barroom in the first half of this thing. Truly, there is something amazing brewing inside Kurt Russell as he peels off line after line in that slow-hand, seductive drawl of his. I said last April that Tarantino should have made a kind of Iceman Cometh out of this character and this setting — it could have been talk- talk-talk for two or even three hours and I, for one, would have eaten it all up. For the first time in his life Tarantino could have delved and dug in. He could have followed his feelings and beliefs and lamentations and just gone for broke. He could have riffed and probed and wondered about every last thing under the sun, and I would have relished it. (Probably.)

But Tarantino and his genre-wallowing partner Robert Rodriguez were committed to their memory-lane concept — making a pair of deliberately cheesey exploitation films that could have played in an urban grindhouse theatre in 1971– and so Death Proof had to leave that Austin bar and head for the hills of California (i.e., that rural winding-road area north of Solvang) and become a dopey but thrilling car-chase movie, which everyone admired for the 100% real, CG-free thrills.

My only beef with this abrupt changeover was that Tarantino totally abandoned his affection for Stuntman Mike by turning him into a raging psycho who moaned and wailed like a nine year-old when things went against him.

What is unquestionable is that by sticking to their Grindhouse concept Tarantino and Rodriguez outsmarted themselves and Harvey Weinstein and most of the ticket-buying Average Joes, who either didn’t get it or decided the idea was too much of a throwaway thing (especially with that three-hour length) and paid to see Disturbia instead.

I suppose I’m just raising a glass to Russell and Stuntman Mike and the movie that Death Proof could have been if Tarantino had had the character and the balls to think beyond doing ’70s genre revisitings and become a real writer and filmmaker, which I thought he might become in the early to mid ’90s before heaving a great sigh and finally realizing he’s too lazy and distracted by this and that to buckle down.

But in spurts and flashes the first half of Death Proof showed again that Tarantino still has the voice and the music. What a shame that he won’t (or can’t) focus and really get down.