I checked the entertainment and movies section of today’s New York Post for my piece about how the revolutionary Best Picture lineup of 1967 (the story of which is richly told in Mark Harris‘s just-published Pictures at a Revolution) to no avail.

I assumed they’d killed it because it was too dense or thinky or whatever. (I tried to write it like a borough guy but there’s a limit to such contortions.) Then my editor wrote back and said no, it’s in the paper — in the Opinion section.

What was I thinking? A totally reported piece about Hollywood then and now, zero opinion, running on Oscar Sunday with no links in the Movie Section. I guess it wouldn’t have made sense to run it in the Classifieds.

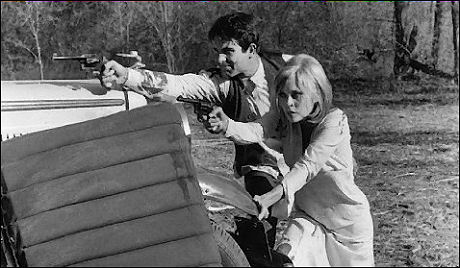

It’s called Year of the Brat with a subhead that reads “In 1967, the Young Turks Took Over Hollywood — And Invented ‘Indie’ Film.” Even if all they accomplished in ’67 — and this was no small potatoes — was to get themselves a solid foothold in a business that would continue to be stodgy and erratic and status-quo-minded in its constant attempts to kowtow to the chumps.

The best quote in the piece comes from Michael Clayton director-writer Tony Gilroy: “All those films and filmmakers [behind edgy 1967 nominees Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate] were jumping off the cliff. They didn’t know what was happening next.

“I think in the last 40 years, it’s become hard to see where the cliff is anymore,” Gilroy states. “There’s been a fundamental shift in what constitutes revolutionary. We’ve been through so much over the years [that] we’ve seen over the abyss. I think movies are less about astronomy today than quantum mechanics. They’re about going in rather than going out.”

On second thought, it’ll be kind of agreeable if Michael Clayton steals the Best Picture Oscar tonight. Quantum mechanics!