And the reaction to Yoostar, the cinema karaoke software with studios licensing clips for Average Joes & Janes to put themselves into movie scenes…? Actually, I’d rather be William Munny in the climax of Unforgiven.

Day: November 27, 2009

Everywhere But Nowhere

“All the airports kind of feel and look the same now,” Jason Reitman told the N.Y. Times‘ David Carr in an 11.25 interview piece. “Some are more beautiful, some are less beautiful, but for the most part you’re going to find a Starbucks in every airport. You’re going to get your coffee and the USA Today or New York Times in every airport. All the things that you want are there, so you can land anywhere, and you feel at home. You’re given the sense that you’re everywhere, but you’re nowhere; that you are constantly with your community, yet you have no community. There’s kind of a terrific irony to that.”

But you do have community in an airport. You’re surrounded by hundreds of people who are just like yourself. You just don’t usually talk to them as a rule. And some airports are more soothing than others, especially those in Germany and Swtizerland.

As I put it without irony on 9.27…

“No man-made atmosphere makes me feel quite as serene as an airport. When I’m waiting for a plane, I mean. (And after I’m through the security scan.) A blissful feeling of being neither here nor there. All my cares and anxieties suspended. It’s actually kind of beautiful.

“I know and accept, of course, that airport environments are no substitute for anything, least of all the real rock ‘n’ roll of life. I only know what I feel when I’m inside them. I’m in a kind of womb — a place in which the normal heave and pitch of things doesn’t happen or disturb. The appointments, challenges, pressures, deadlines — all that will surround me and more after I’ve landed. Expected, understood. But what a charmed feeling it is to be within an airport with all of that stuff outside, and with nothing to do inside but chill. I especially love three- and four-hour layovers. I adore browsing around, having a cafe au lait, leafing through magazines, looking at the hundreds of travellers. (Especially the women.)”

Downish, Forlorn

“I’m really disappointed” in Barack Obama, writes playwright Christopher Durang. “I mean, I know he’s way better than Bush. I guess I miss the oomph that LBJ had both in civil rights and in getting Medicare/Medicaid passed into law. Then he let his mistakes in fighting in Vietnam sink him.

“Obama is cool and charming. But oomph? Seemingly not. Hip and appealing. Yes, but can he do aggressive arm twisting to get something passed? Can he bring some power and aggressiveness to explaining things the country needs, to get people on board?” Not so much. So far.

“And if Obama isn’t the one to change things in a major way for the better — health care, environment, people’s rights — who is? I am a disappointed idealist.”

Not Guilty, Bad Brief

The Toronto Star‘s Peter Howell has bravely compared Gone With The Wind, a metaphor about the miseries and deprivations of the Great Depression of the 1930s (and a comment about how the nicest people aren’t necessarily the ones who do well in tough times, and vice versa) with New Moon, a stunningly dull and tension-less Mormon metaphor about just saying no to pre-marital sex.

Howell is one of the nicest and smartest guys I know and one of the best film critics bar none, but this article is…uhm, unpersuasive. To me, anyway.

Howell actually calls New Moon a “well made, competently acted” thing that “properly complements the Twilight book series.” It’s “not one of the year’s best movies,” he allows, “but it’s a far cry from the worst.” And the critical slamming of it, he suggests, was due to “the same sexism that prompted many critics to dismiss Sex and the City completely out of hand, simply because it was perceived to be a movie for women, and thus not a movie to be taken at all seriously.”

Nope, wrong. It’s not that New Moon is aimed at women — it’s the obvious fact that Catherine Hardwicke‘s Twilight, released a year ago, did a much better job of tapping into the panting Bella Swan + Edward Cullen current than Chris Weitz did in New Moon. Much. As in don’t even compare them. It’s not that New Moon is too girly and swoony — it’s not girly and swoony enough.

On top of which Howell totally ignores the ghastly season-changing sequence in New Moon that became an instant laughing stock — one of the stupidest such sequences in motion picture history.

The fact that title cards indicating the passing end-of-the-year months were deemed necessary to insert (presumably due to test-screening reactions from Eloi audiences that indicated confusion about why the front lawn had changed color and was thereafter covered with leaves and then snow) is one of the most persuasive and depressing indications that there are some amazingly stupid people out there.

Howell not even mentioning this sequence, which film professors will be showing to their students for decades to come as an indication of societal rot and collapse, completely destroys his other arguments. It’s too glaring and too comical to be brushed under the rug, and failing to at least acknowledge it when a writer is laboring to defend New Moon means that attention isn’t being paid.

And I for one didn’t rip the Sex and the City movie because, as Howell suggests, “it was aimed at women and therefore not to be taken seriously.” I was morally offended by that film. I called it “a grotesque and putrid valentine to the insipid ‘me, my lifestyle and my accessories’ chick culture of the early 21st Century.” I didn’t call it a movie that Satan himself would have been proud to have directed, but I should have.

“The soul of this movie is infected with gross materialism, the flaunting of me-me egos and the endless nurturing of the characters’ greed and/or sense of entitlement,” I said. “It’s all about money to piss away and flashy things to wear and lush places where the the girls lunch and exchange dreary confessional chit-chat. And this, mind you, is where millions of middle-class women in every semi-developed country around the globe live in their dreams. They’re going to this movie right now in multitudes. Sad. Really sad. Because SATC is crap through and through.

“A few items back I called Sex and the City a Taliban recruitment film. All I know is that I felt ashamed, sitting in a Paris movie theatre, that this film, right now, is portraying middle-class female American values, and that this somehow reflects upon the country that I love and care deeply about. It’s a kind of advertisement for the cultural shallowness that’s been spreading like the plague for years, and for what young American womanhood seems to be currently about — what it wants, cherishes, pines for. Not so much the realizing of intriguing ambitions or creative dreams as much as wallowing in consumption as the girls cackle and toss back Margaritas.

“All I know is that the faux-splendor of the movie — the insipid Marie Antoinette-ishness of the damn thing with the look-at-me clothes and sets and nouveau-riche ickiness of the apartments and restaurants — felt to me like a kind of hell.”

Role Model

The way I hear it Clint Eastwood arrived in South Africa to shoot Invictus on a Friday, never having visited the country before as an explorer looking to absorb and learn. He began shooting two days later (i.e., the following Monday) and, typically for Clint, shot it fairly quickly — two days under schedule, I’m told. He would always finish at five and then, my source says, work out for a couple of hours each day.

My heart and admiration goes out to anyone with that level of vigor and discipline at an age when most people have downshifted if not ceased operations altogether. The guy is amazing — an inspiration. Daily workouts are obviously a way of keeping flush and toned and attuned and overpowering the natural aging process, which tends to begin shutting things down once you’ve hit your late ’70s or thereabouts, if not sooner.

Clint “obviously knows what’s coming” — who doesn’t? — “and that’s why he’s moving so fast and doing one film after another, and making them so cheaply that no one’s going to say ‘no’ and knowing all the while that his brand has an intrinsic value and so on.” I just have to shake my head and go “wow.” Talk about being the captain of your soul.

Leadership

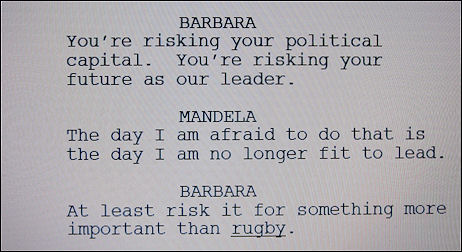

Pamela Ezell‘s 11.27 Huffington Post Invictus piece notes several parallels between former South African president Nelson Mandela and U.S. president Barack Obama. First black president, humble backgrounds, preachers of tolerance and forgiveness despite haters, etc. But the Mandela-Obama parallel falls apart in Clint Eastwood‘s film when Morgan Freeman‘s Mandela is told he’s risking his political capital, and he replies “the day I am afraid to do that is the day I am no longer fit to lead.”

Is there anything less Obama-like than a core belief that a leader must sometimes risk much if not all in order to get the right thing done? Has there ever been a president with less backbone — with more of a mushy cottonball approach to leading and using power than Obama? Has there ever been a president who’s been less inclined to take any risks whatsoever? Who’s been more willing to bend over and defer to his enemies and say to the worst scummiest Republicans, “Hmmm…okay, maybe you guys have a point”?

Here’s another line that Mandela says in the film:

It’ll be an ice-cold day in hell when Barack Obama says to a White House adviser, “In this instance the people are wrong, and it is my job as president to make them see that.” The mantra of Barack Obama is, “We know what to do and we know what’s right, but it’s better to cave in and get along because that way our poll numbers will be steadier. Because…you know, I can’t afford to be seen as an angry black guy. I don’t have that authority that Franklin D. Roosevelt had when he became ‘a traitor to his class.’ The right is too powerful and there too many crazies out there. It’s all I can do to chill them out.”

Mitigating Circumstances

As everyone knows, the title of Clint Eastwood‘s Invictus is taken from William Ernest Henley‘s short poem of the same title, which was first published in 1875. “Master of my fate, captain of my soul, bloody but unbowed,” etc. It’s one of the best right-wing poems of all time and I respect it as such, but for most of us Henley’s words fly better on the page than they do in real life.

The best stand-alone right-wing sentiment I’ve ever heard is “better a general in hell than a corporal in heaven.” Because for most conservatives, power — the ability to choose and make moves as a rugged stand-alone entity without having to bend over or take any crap from bureaucrats or mealy-mouths — is all.

Invictus Is…

The one sterling asset in Clint Eastwood‘s Invictus is…actually, make that two sterling assets. One is the fact that Eastwood is Eastwood and that there’s something I love about sinking into his films, even when they’re not double-grade-A. The other is Morgan Freeman‘s performance as Nelson Mandela — a thing that will carry Invictus along with ticket buyers and probably reap Oscar glory.

Morgan Freeman in Clint Eastwood’s Invictus

Freeman’s performance is not a deep-mine thing or a dazzling revisiting of a still living-legend whose face and manner are well remembered by millions. But it’s really quite satisfying — soothing — to watch Freeman, nearly a dead ringer, adopt a slight accent and step into Mandela’s shoes and walk around with a slight stoop and a faint grin and radiate that serene wise-man thing.

There’s no question Freeman will end up as one of the five Best Actor nominees, and I’m betting right now that he’ll win. He’s obviously playing a more stirring and inspirational guy than George Clooney‘s Up In The Air traveller, and a more sympathetic and charismatic figure than Daniel Day Lewis‘s Guido in Nine. He’s dealing with the same sort of historical turf that Christopher Plummer stands on in The Last Station, but Freeman has better lines and a stronger spirit.

His toughest competitors are A Single Man‘s Colin Firth, The Hurt Locker‘s Jeremy Renner and A Serious Man‘s Michael Stuhlbarg. But we all suspect that two out of these three are facing uphill odds, under-valued as they currently are by go-along pundits.

Otherwise Invictus has problems, but not ones that involve what it is. The problems it has are about what people are expecting it to be.

Invictus is a nice, cleanly told, mildly stirring South African sports film that should have been released in the late spring or early summer. Because if it had been it wouldn’t have all this weight on it. It could have been directed by Roger Donaldson, and I don’t mean that as a put-down to Donaldson or Eastwood. It just is what it is, but the fact that it’s the latest Eastwood film with a December opening has everyone hot and bothered. Well, cool down.

Invictus does remind us of what a centered and wise and very cool guy Mandela was — it gives off a contact high in this respect. But it’s all exposition, exposition, exposition and more exposition. And there’s almost no “story” in the sense that there are no character turns, no twists, no nothing in the way of surprises or intensifications. A good amount of it — most of it, really — is about South African government employees watching rugby games or standing around offices or sitting on buses or in the backs of cars or watching TV. (TV screens get a major workout in this film.) Or about athletes jogging and playing rugby and working out.

Invictus is about an “important” subject — one we should think about and perhaps learn from — but it mainly just ambles along. It kinda gets off the ground at the end, but rousing sports-movie finales don’t travel like they used to because we’ve seen them so damn often. You can’t just have the good-guy team win and show everybody cheering. That’s not enough any more.

This is one reason why Invictus doesn’t really go “wow” or “kaboom.” It’s fine and very agreeable in some respects. Anyone who writes in and says “You’re wrong” or “I loved it!” will not get put down in this corner. But there’s no getting around the fact (and it pains me to say this, being a major fan of Unforgiven, Play Misty For Me, High Plains Drifter, Breezy, Million Dollar Baby and Gran Torino) that Invictus is second-tier Eastwood.

Freeman and the take-it-easy, don’t-push-it quality to Clint’s direction are two winning elements. But it should have been a more layered thing. On one level there would have been what we have now — an above-board, what-you-see-is-what-you-get story about how a rugby team and a championship game helped bring a divided nation closer together. And there also would have also been…something else. A more penetrating look at the travails and fears of Mandela or Matt Damon‘s Francois Peinaar. A parallel story, a powerful subplot, a more prominent undercurrent or some other big thematic echo. Something.

Morgan Freeman, Matt Damon

The first half-hour is the best part, by far. Freeman’s manner and personality are quite winning, and I was particularly impressed by a scene in which he gives a low-key address to some white staffers who are presuming they’ll be fired by the new Mandela administration. There’s also a good moment as the film begins in which we’re shown a white high-school rugby team practicing behind a chain-link fence and some young black kids playing rugby in the lot across the street, and the way they react differently when Mandela’s little motorcade drives by. All of this early stuff is quite good.

But once the rugby-championship element kicks in Invictus starts to flatten out and restrict itself to lateral passing back and forth. People said that Martin Scorsese‘s The Age of Innocence was a movie about cufflinks. And that Anthony Minghella‘s Cold Mountain was about a man walking through the woods. Boiled down, Invictus is (after the first half-hour) about people watching TVs, watching the rugby team play in a stadium, talking about what they’re seeing or thinking, and commenting on what may or may not happen.

And feeling exhilaration, of course, when the Big Game finally happens and (spoiler! happened 14 years ago!) South Africa beats New Zealand. That’s all it really is.

I almost admire Eastwood for keeping it as simple and straightforward as it is. It’s nice to see restraint and centeredness in a director, and there’s something very elegant about the way he steers Invictus along at 35 mph without cranking things up for the sake of cranking things up.

I know, I know — a satisfying plate of pasta doesn’t have to be “brilliant.” It just has to be carefully prepared and well seasoned and made with love. Invictus is a very pleasant and mildly stirring bowl of fettucini with a highly agreeable lead performance by Freeman. But it’s not one of those ratatouille dishes that win awards and inspire raves from restaurant critics.

Wait In Line, Fella

So Newsweek‘s David Ansen, Variety‘s Todd McCarthy and the Hollywood Reporter‘s Kirk Honeycutt get to ignore the 11.30 Invictus review embargo and everyone else has to wait…is that it? Because they’re big shots with special privileges? Are we still living in 1997?

And now Huffington Post-er Pamela Ezell has chimed in with an opinion — “On a scale of one to 10, Invictus is a six,” she says. “Add it to your Netflix queue or watch it on pay-per-view. Those lucky enough to be on a trans-Atlantic flight next year will probably have a chance to see Invictus on the plane, since its political theme and World Cup rugby depictions will undoubtedly make the film more popular abroad than it is here.”

A columnist friend says he’s waiting for Monday anyway — “What’s the difference? Nobody’s reading this weekend” — but the dam is clearly cracking and all bets are off. I’ve been chewing Invictus over in my head and may as well unload now. It’s a likable, very decent film in many respects — Morgan Freeman is delightful as Mandela, and an almost certain Best Actor nominee — but it seems fair to mention other impressions.

What Kind of “Good”?

“Invictus is a very good story very well told,” writes Variety‘s Todd McCarthy. Wait a minute…a “good story”? The use of this term at the beginning of an important review of an end-of-the-year film by a major director calls for a full examination of its meaning.

Morgan Freeman (center) as Nelson Mandela in Clint Eastwood’s Invictus.

I’ve seen Invictus myself and on a certain level McCarthy is right. The story of South African president Nelson Mandela (Morgan Freeman) using the symbolism of sport — i.e., urging unanimous and fervent support of the all-white Springboks rugby team in their goal of winning the 1995 World Cup championship — to unify his racially divided nation is, if you’re at peace with director Clint Eastwood‘s even-tempered, mild-minded shooting style, “well told.” I’m just not sure about the material.

To me the term “good story” is synonymous with “good yarn” — a tale that intrigues and enthralls by…well, usually by planting seeds in the beginning that germinate and sprout into a full and satisfying finale — one that feels natural and true and has a good kick or payoff. We all have our definitions for what “full” and “satisfying” means, but I suspect that what McCarthy meant when he said “good story” is one that is about goodness, or one that is “good” to hear and consider because it says “good” things about human nature, especially when a “good” man finds the strength to lead people in the direction of goodness, which is to say forgiveness and a “thumbs up” attitude that echoes Bob Dylan by saying “don’t look back.”

That aside, McCarthy steps back and, in my view, doesn’t full engage with Invictus, certainly not as much as he could if he wanted to. What is in play here is a justified respect for and allegiance to Eastwood, and McCarthy writing about the film in the same settled-down, measured, and un-throttled way that Eastwood deals with Mandela’s rugby story.

Eastwood’s film, says McCarthy, “has a predictable trajectory, but every scene brims with surprising details that accumulate into a rich fabric of history, cultural impressions and emotion.

“Once again in his extraordinary late-career run, Eastwood surprises with his choice of subject matter, here joining a project Freeman had long hoped to realize. In fact, the filmmaker has frequently dealt with racial issues in a conspicuously even-handed manner, most notably in Bird, and hiscalm, equitable, fair-minded directorial temperament dovetails beautifully with that of Mandela, much of whose daily job as depicted here consisted of modifying and confounding the more extreme views of many of his countrymen on both side of the racial divide.

“Mandela is the lynchpin of Invictus, whose title is Latin for “unconquerable” and comes from a stirring 1875 poem by British writer William Ernest Henley. Although far from a conventional biography, Anthony Peckham’s adaptation of John Carlin‘s densely packed book Playing the Enemy commences with Mandela’s extraordinary transition from imprisonment to the leadership of a country that easily could have fallen into a devastating civil war.

“As he takes office, Mandela allows that his greatest challenge will be successfully relaxing the tension between black aspirations and white fears. Pic adroitly avoids becoming mired in the minutiae of political score-settling by summing up racial suspicions through the prism of the new president’s security detail. Mandela’s longtime black bodyguards are shocked when their ‘Comrade President’ forces them to work with some intimidating Afrikaners, experienced toughs who until very recently were no doubt striking terror into the hearts of the black population.

“Directed by Eastwood with straightforward confidence, the film is marbled with innumerable instances of Mandela disarming his presumed opponents while giving pause to those among his natural constituency who might be looking for some payback rather than intelligent restraint.

“Freeman, a beautiful fit for the part even if he doesn’t go all the way with the accent, takes a little while to shake off the man’s saintlike image, and admittedly, the role of such a hallowed contemporary figure does not invite too much complexity, inner exploration or actorly elaboration. That said, Freeman is a constant delight; gradually, one comes to grasp Mandela’s political calculations, certitudes and risks, the troubled personal life he keeps mostly out of sight, and his extraordinary talent for bringing people around to his point of view.

“Where the rugby match is concerned, that talent is manifested by how, over tea, Mandela personally appeals to the captain of the South African team, the Springboks. A blond Afrikaner with no discernible politics, Francois Pienaar (Matt Damon) would just like to lift the squad from its present mediocrity. But Mandela quotes inspiringly from the poem — ‘I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul’ — speaks of leading by example and exceeding expectations, and leaves Pienaar astonished at the idea that they can dare to dream about winning the World Cup.

“Just as it’s disinclined to offer a primer on South African politics, the film refrains from outlining the rules of rugby; the viewer just has to jump in and surmise that it’s something like a cross between soccer and American football. What the film conveys with tart economy is that rugby was a white game, scorned by blacks; as one man puts it, ‘Soccer is a gentleman’s game played by hooligans, rugby is a hooligan’s game played by gentlemen.’

“In a magnificent irony, the team the mostly white South African squad ultimately faces in the title match is a mostly white New Zealand team called (because of their uniforms) the All Blacks. The climactic faceoff, played in front of 62,000 fans at Johannesburg’s Ellis Park Stadium roused by the presence of Mandela himself, lasts 18 minutes of screen time; when such an event plays out like this in real life, it’s often exclaimed that it could only have been scripted for the movies. Here, it’s real life dictating the incredible scenario.

“With the exception of the meeting with Mandela and a couple of family scenes, most of Damon’s screen time is spent in training or on the field, and it’s meant as highest praise to say that, if he weren’t a recognizable film star, you’d never think he were anything other than a South African rugby player. Beefed up a bit (or, perhaps more accurately, slimmed down somewhat from “The Informant!”) and employing, at least to an outsider’s ear, an impeccable accent, Damon blends in beautifully with his fellow players.

“Some of the most amusing and telling scenes throughout involve the bodyguards, whose body language, facial expressions and intonations of minimal lines convey much about the uncertain state of things in the country.

“Shot entirely on location in South Africa, Invictus looks so natural and realistic that it will strike no one as a film dependent upon CGI and visual effects. In fact, the climactic match would not have been possible without them, as virtually the entire crowd was digitally added after the action was filmed in an empty stadium. You really can’t tell.”

McCarthy is right again — Invictus has the best fake multitudes sitting in a stadium CG I’ve ever seen. Very impressive. Cheers to special effects supervisor Cordell McQueen and visual effects coordinator Eva Abramycheva.