The best explanation I ever gave to my kids about what happens when you die was that “you become a baby again, except most don’t remember who they were before they came out of their mommy as babies, so basically they’re starting all over again with a fresh slate.”

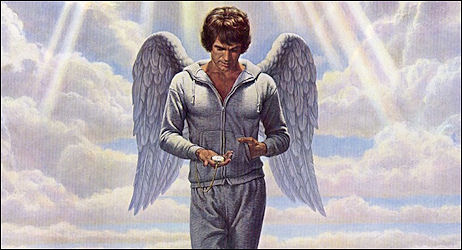

I put that together from Buddhism, from that old “life is a fountain” line, and from Warren Beatty and Buck Henry‘s Heaven Can Wait. Most people want (or need) to believe in some kind of serial continuity. We all suspect that the Woody Allen view of death is probably correct, but we’d rather not go there. We’d rather invest in some vague idea that (a) when your body dies that’s all she wrote, but (b) something in you keeps on by transferring or re-inhabiting (i.e., finding a new host) or going all Stanley Kubrick cosmic.

Or by returning as a dog or something. Wasn’t that a plot of an ’80s cop comedy?

So what happened between Roger Ebert and The Lovely Bones? The film’s presentation of heaven (a mixture of Alice Sebold’s story, which envisions a kind of continuity, and Peter Jackson‘s need to keep work coming into WETA) really rubbed Ebert the wrong way. He didn’t just say “not a vision that enthralls me” but “good God, man…how dare you?”

In Ebert’s view, The Lovely Bones “is a deplorable film with this message: If you’re a 14-year-old girl who has been brutally raped and murdered by a serial killer, you have a lot to look forward to. You can get together in heaven with the other teenage victims of the same killer and gaze down in benevolence upon your family members as they mourn you and realize what a wonderful person you were. Sure, you miss your friends, but your fellow fatalities come dancing to greet you in a meadow of wildflowers, and how cool is that?

“The makers of this film seem to have given slight thought to the psychology of teenage girls, less to the possibility that there is no heaven, and none at all to the likelihood that if there is one, it will not resemble a happy gathering of new Facebook friends. In its version of the events, the serial killer can almost be seen as a hero for liberating these girls from the tiresome ordeal of growing up and dispatching them directly to the Elysian Fields. The film’s primary effect was to make me squirmy.

“It’s based on the best seller by Alice Sebold that everybody seemed to be reading a couple of years ago. I hope it’s not faithful to the book; if it is, millions of Americans are scary. The murder of a young person is a tragedy, the murderer is a monster, and making the victim a sweet, poetic narrator is creepy. This movie sells the philosophy that even evil things are God’s will and their victims are happier now. Isn’t it nice to think so. I think it’s best if they don’t happen at all. But if they do, why pretend they don’t hurt? Those girls are dead.

“I’m assured, however, that Sebold’s novel is well-written and sensitive. I presume the director, Peter Jackson, has distorted elements to fit his own ‘vision,’ which involves nearly as many special effects in some sequences as his Lord of the Rings trilogy. A more useful way to deal with this material would be with observant, subtle performances in a thoughtful screenplay. It’s not a feel-good story. Perhaps Jackson’s team made the mistake of fearing the novel was too dark. But its millions of readers must know it’s not like this. The target audience may be doom-besotted teenage girls — the Twilight crowd.”

All things are God’s will, Roger — the good, the evil, the ugly and the banal. God, who is not a celestial football coach urging humans to do their best in their fight against the opposing Devil team, doesn’t pull strings in order to make good stuff happen occasionally. He/She just floats around up there like vapor and says, “Whatever, guys…it’s your show. I’m not in this. You know…absentee landlord and all the rest of that Al Pacino Devil’s Advocate crap?”

The creation that He/She put together has always been easy access for all types and all manner of behavior. You have to try and do good for yourself and others within the short time that you have on this planet and that’s all. Because we’re all headed for the mulch pit.