William S. Burroughs said the above at some literary gathering I attended in midtown Manhattan around ’80 or thereabouts. It came back to me as I read Charlie Savage‘s half-fair, half-dismissive N.Y. Times review of Owen Gleiberman‘s “Movie Freak“, which I riffed about on 2.18.

There’s only one churlish paragraph, really, but I was quite bothered by Savage laying into Gleiberman for…well, the crime of being honest. Which isn’t a crime, of course. Not in my book, at least. Writers have to be self-exposing at all times and under all circumstances, especially when recalling their own checkered histories. Even if this involves confessions that aren’t entirely flattering.

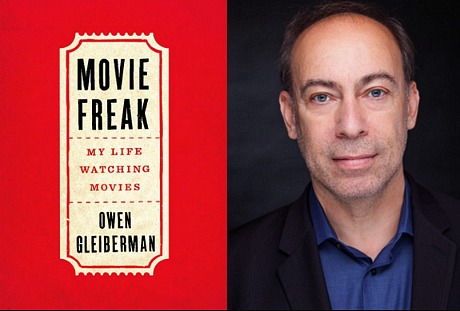

Gleiberman’s critiques has always laid things plain on the table, and it’s this quality, I feel, that makes “Movie Freak” a livelier, more engaging read than, say, some dry recounting that focuses only on the job or the reviews.

Let’s examine the pissy paragraph. Portions of “Movie Freak” “are often off-putting,” Savage writes. “With inconsistent self-awareness, Gleiberman writes about himself like a patient talking to his therapist, but readers are not being paid $200 an hour to empathize as he tells story after story.” Except Gleiberman is a gifted writer, Charlie, and that plus the confessional aspect is what tends to float boats. Or mine, at least.

Savage conveys annoyance at Gleiberman mentioning that at one point his “very being…had been formed to a degree by pornography” and that during a certain period he spent “as much time as possible hitting on women in the office.”

Yep, somewhat embarassing, but if you don’t admit to this kind of thing (especially if it’s the real thing) what does a memoirist have to show? The last time I looked amplified hormonal urges were fairly prevalent among most younger fellows. If you ask me younger women should avoid 20-something jackrabbits altogether and instead focus on guys in their 30s. Or, you know, guys who’ve managed to grow a little compassion and sensitivity and learn how to keep things in check.