Click here to jump past HE Sink-In

It’s a plain, straight fact that Cary Fukunaga‘s Beasts of No Nation is a piece of devastating, world-class art — undeniably alive and probing and humanistic, a film about conscience and savagery and moral choice. It goes without saying that such a film requires award-season acclaim, and that denying it this will be some kind of perverse. But from the moment Beasts opened simultaneously on Netflix and in a relative handful of upmarket theatres on 10.16, three things have become apparent, and it almost takes a degree in marketing to figure out the whole equation.

One, a consensus has developed among film Catholics that despite its difficult subject matter (i.e., African child soldiers conscripted and goaded into committing atrocities during a civil war) Beasts is nothing short of a jolting, half-hallucinatory masterpiece — a 21st Century Apocalypse Now by a director with a momentous career ahead of him. It’s one of the few noteworthy films of 2015 to be spoken of in genuinely worshipful terms. For a few weeks now people like Jake Gyllenhaal, Ben Affleck and Sally Field have been hosting screenings and more or less dropping to their knees. Robert Downey, Jr. is also a fan. Many people are.

Two, some exhibitors (i.e., AMC Cinemas, Carmike Cinemas, Cinemark, Regal) have turned their backs over the day-and-date thing, and some Academy members have said in recent party-chat conversations that Beasts needs to be disciplined (i.e., not voted for) for the same reason, despite the fact that the quality of it demands attention at the very least, and the fact that Netflix is simply perched at the forefront of emerging release patterns.

And three, as was the case with Steve McQueen‘s 12 Years A Slave, winner of the 2013 Best Picture Oscar, some people just won’t see it. Some women, I’ve heard, just don’t want to watch a young boy (i.e., Abraham Attah‘s Agu) commit horrendous acts and in so doing lose his humanity. (Then again if they saw Beasts they’d know that Agu not only escapes his wartime servitude near the end but confesses his sins in a plea for redemption.) But all serious film lovers understand that when a film is said to be really and truly exceptional, you have to put aside your concerns and just submit. You have to let it in.

This is what I’ve been saying since I caught Beasts of No Nation a couple of months ago at the Telluride Film Festival. You have to watch it even you suspect it might be a rough sit. Except it isn’t. Because despite the horrors of war, the movie keeps you somewhere between a state of observation and cinematic suspension. It’s about real things (some of them ghastly) but it’s not “realism” any more than Francis Coppola’s 1979 epic fit that definition.

Fukunaga is not an exploiter. Frame for frame it’s clear that every shot and cut in Beasts was chosen to further a moral point. In every minute of this film Fukunaga is saying to the viewer, “I know as well as you do that all war involves a suppression of moral focus and a submission to savage impulses, but in all but very few of us morality hangs on…it survives and pushes through and eventually resurfaces despite the presence of constant, day-to-day brutality.”

As I wrote on 9.7, “We’ve all seen violent films that try to merely shock or astonish or cheaply exploit — Beasts of No Nation is way, way above that level of filmmaking. It’s often about cruel, horrifying acts but filtered through a series of moral, cultured, considered choices, and about what Fukunaga chose to use and not use and how to assemble it all just so.”

Beasts, agreed, is not what your mother might call “pleasant viewing” but it’s always a churning, ravishing thing, a cauldron of mad-crazy intense, something ripe and authentic. And never without exuberance or humanism or a moral compass. And made, mind you, by a cultivated artist — a guy of moderate temperament who wears fashionable glasses and cool-looking sweaters but who holds back just enough but never wimps out, who jumped right in and shot the whole thing himself in Ghana over a mere seven weeks, a guy who knows how to whip up strange brews and visual lather.

Half of Beasts is gripped by madness — a kind of fever known only by war veterans and particularly (as this is the specific focus of the film) by children who’ve been forced into killing by ruthless elders. It’s harsh and brutal but poetic — one of those films that’ll hold up a decade or two or a half-century from now. Variety‘s Justin Chang called it “orchestrated and painted and cooked to a full boil…start to finish it has a feeling of keen impulse mixed with carefully honed art.”

Beasts of No Nation is one of the few films from which I haven’t precisely derived “enjoyment” that I’ve watched twice, and which I could easily see a couple of more times without breaking a sweat.

Beasts should be a Best Picture nominee, period. Trust me, you’ll feel good about voting for it in the morning. And you’ll probably need something to feel good about if you include Ridley Scott‘s The Martian among your top-five films of the year.

Fukunaga definitely deserves a Best Director nomination for not only adapting Uzodinma Iweala’s same-titled book but shooting it himself Soderbergh-style, and doing so in the rough and tumble of rural Africa in less than two months. Idris Elba, who plays the central figure of the “Commandant” who turns Agu into a murderer, could see some action as a Best Supporting Actor contender. Attah surely deserves special attention for nailing a tough experience with his first-ever performance.

Anyone who attends Sunday services at the Church of the Devoted Cinephile needs to grim up, man up and see this film. Everyone. If you avoid it I swear you’ll be embarassed to admit this down the road. You’ll be at some party and some person you’re highly impressed by or whom you’d like to work with will ask if you’ve seen it and how good it is, and you’ll be unable to join the conversation. Enough said.

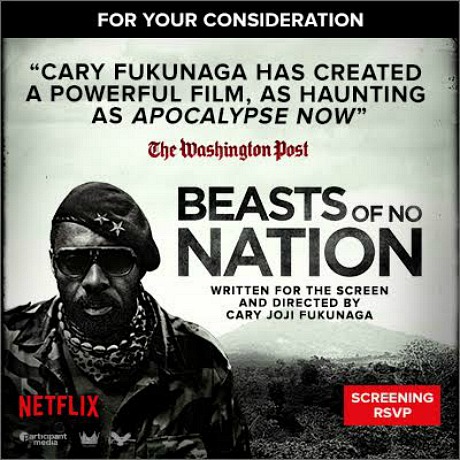

Beasts of No Nation director Cary Fukunaga and star Abraham Attah just after the film’s premiere at the Telluride Film Festival.

Beasts of No Nation director Cary Fukunaga and star Abraham Attah just after the film’s premiere at the Telluride Film Festival.