Albert Finney, rest his soul, was always a flinty, lion-like actor of the first alpha-male order. When I recall his best middle-period work I think of the angry drunk in Under The Volcano, George Dunlap in Shoot The Moon, “Sir” in The Dresser — edgy contrarians, bellowing, lashing out. But there’s a difference between delighting in a young actor’s dash and pizazz, and admiring or saluting the work of an older, non-dashing fellow who enjoys bending the elbow and has settled into a certain workmanlike approach to his craft.

Much of Western Civilization (certainly the female half) swooned over the slender, rakishly handsome Finney in his mid to late 20s, the fellow who starred in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (’60), Tom Jones (’63) and Two For The Road (’67). I wish I could have seen him perform on-stage in the late ’50s, when he was completely engaged and on fire.

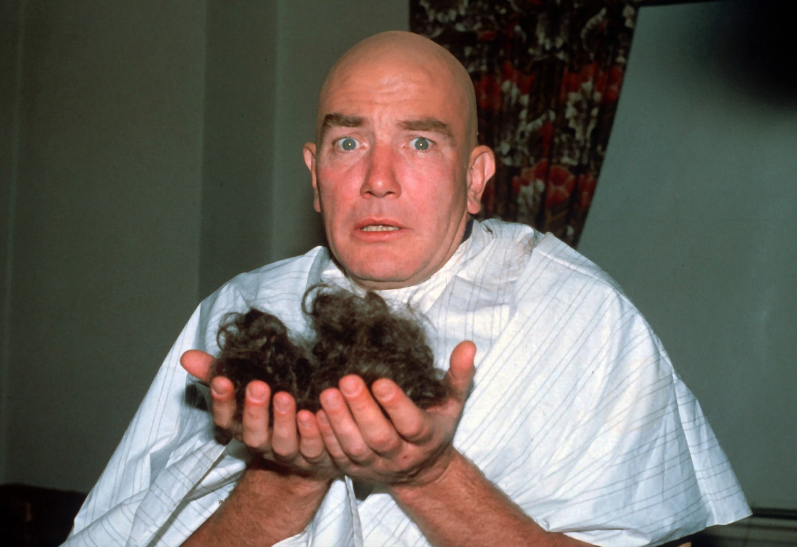

But then Finney’s drinking started to add to his frame and he more or less become a chunky character actor of consequence, certainly by the early ’70s, and that is who and what Finney was for most of his life — a gifted, justly admired, somewhat beefy and then flat-out bulky guy who was never less than first-rate when the writing was up to speed and the pressure was on.

In a 6.24.82 Rolling Stone piece (written by David Rosenthal) called “This Might Possibly Be Albert Finney,” the 46-year-old actor spoke about his early days and the arc of his career:

“’As a youth, it seemed relatively attractive to be the roaring boy,’ Finney says. ‘You know, where you drank at the pub during lunchtime and then gave a performance. I went through a period where I thought, ‘Oh, yes, it’s terrific to be like that, to be John Barrymore,’ that kind of syndrome. I found the idea of it appealing, playing that role, but my system in those days — it’s [become] more hardened since — actually couldn’t cope with it. I used to go on these drinking sessions with various mates, and after a bit, they’d help me out of the bar so I could throw up somewhere.

“I guess it’s possible that it was a kind of escape hatch. If you’re regarded as someone of talent, expected to be an achiever, perhaps if you screw yourself up, they’ll say, ‘Well, if only he hadn’t become an alcoholic, he would have fulfilled the promise.’ But it didn’t happen for me because I simply couldn’t do it. I could not be John Barrymore.’

“It isn’t that Albert Finney is abstemious these days, only that he generally stays away from the hard stuff. He can imbibe quite seriously, but no one’s ever mentioned him in league with, say, Peter O’Toole. And it has never, by all accounts, affected the work. ‘Albert could drink a gallon of wine at night, be on the set the next morning and do everything perfectly the first time,’ says John Huston, the director of Annie.

“Yet there’s something about Finney, perhaps the tendency of his face to look tired when still, the tousled hair and crow’s feet, the ofttimes slow, deliberate speech that makes some unnecessarily wary.”

HE’s favorite middle- and late-period Finneys: Charlie Bubbles (’68), The Picasso Summer (’69), Gumshoe (’71), Murder on the Orient Express (as Hercule Poirot — ’74), [Looker and Wolfen were crap], Shoot the Moon (’82), The Dresser (’83), Under the Volcano (’84), Miller’s Crossing (’90), The Green Man (early ’90s British miniseries), Erin Brockovich (’00), Traffic (’00), Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (’07).

Diverting But Negligible: The Bourne Ultimatum, Skyfall. On second thought: His Winston Churchill in The Gathering Storm was actually pretty good.

Back to the Rosenthal Rolling Stone piece: “There is no certainty to Finney, just an abundance of vague mysteries that sometimes puzzle his colleagues and that he embellishes with unpredictable flights across the public eye.

“There he was, a star before his twenty-fifth birthday, the finest of his generation, they attested, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, a film that revolutionized British cinema, already under his belt; Luther, a smash in London and on Broadway; Tom Jones awakening an entire generation to the virtues of youthful, bawdy lust. Approbation and multipicture deals danced seductively around his unswelled head. Lawrence of Arabia? He had already turned it down. David Merrick wanted him to stay in New York? Forget it. Well, what do you want to do, Albert? What is it you want?

“Nothing.

“Albert left the iron glowing hot and took off around the world. The brightest young performer around, written up everywhere as destined to be the leading man of the era, packed a bag and headed through Fiji, Pago Pago, the West Indies, Italy, Greece — anywhere he decided to move. A year of self-exile before it was fashionable for movie stars to make themselves scarce.

“He did return, of course, to the stage, rebounding from the failure of Night Must Fall, a disastrous film made before he left, by winning Britain’s award as best actor in 1966. Then he escaped to the south of France to shoot Two for the Road with Audrey Hepburn. But something, it seemed, was still missing.

“So a year was spent on Charlie Bubbles. It is the only film Finney has directed — a year of his life behind the camera, starring in front of the camera, producing the project from start to end. It was a highly personal, beloved affair, this ninety-one-minute tale of a successful writer, wary of and alienated from his good fortune, seeking his roots, ultimately floating away on a bouquet of balloons. It was an exceptional film treated unexceptionally by audiences.

“’If they reject Charlie Bubbles, they reject my feelings, attitudes and everything around me,’ Finney had warned. And so he withdrew again, thinking things out on Corfu, surfacing in the black comedy Gumshoe and making a surprising sensation in the musical Scrooge. But for six years there were no West End performances, the leading stage actor of London brooding offstage. Unprovoked, disinterested, waiting for good shows.

“Then, in 1972, a funny thing happened. A little play — a harsh, naturalistic domestic drama called Alpha Beta — opened starring Albert Finney. The juices, the adrenaline, came seeping through the veins, slowly at first, a percolation followed by a pressured surge. Acting, all at once, was relevant again. The turmoil of performance, its ecstasy, watching the audience respond to him. Revitalization.

“He even dressed up like a grotesque oil slick to play Hercule Poirot in Murder on the Orient Express. Praised for this impersonation, this triumphant big-screen return, Albert did the obvious; he stayed out of movies for six years and devoted his life to the National Theater — repertory, the major Shakespeare roles, modern masterpieces — and felt fulfilled. He even recorded, in 1977, an album of his songs for Motown.

“And then, abruptly it seems, he absented himself from the stage once more and came to America to do five pictures — Looker, Wolfen, Loophole, Shoot the Moon and Annie — back to back.

“Even to Albert Finney this odd pilgrimage defies pat explanations. He tries to fill in the gaps, or, at times, evade them, a cautious man propelled by instinct and contradiction.

“‘When I took the year off after Tom Jones, I don’t know why. I suppose I wanted to travel a bit. It may have been that I didn’t know what I wanted; I was afraid of what I wanted to do next, ’cause I was hot. Jesus, it suddenly seemed important what I did next, so I said to hell with it. So I didn’t do shit. I didn’t have to do anything next.

“And I always wanted to wander. I also think I’m good as an actor. I’m not saying I can act terrific or great, but I can act good. And what I’ve always believed is that I’ll get a job.”