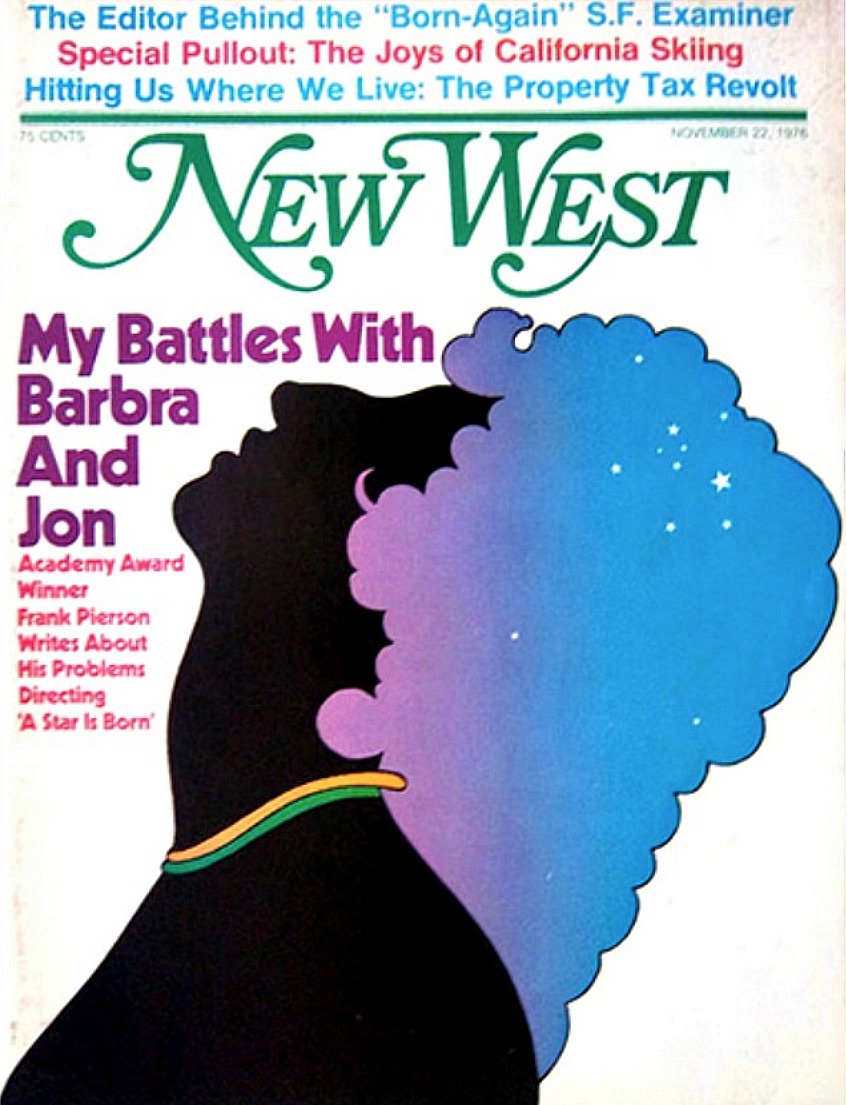

Frank Pierson‘s “My Battles With Barbra And Jon” is/was a New West article that was published just after the 12.19.76 opening of Pierson, Barbra Streisand and Jon Peters‘ A Star Is Born.

I mentioned Pierson’s piece in yesterday’s “Soggy Speculation Thickens” post, but a link on the Barbara [Streisand] Archives website has been removed.

Last night I found the Pierson piece on the Wayback Machine. It’s a longish read.

Key passage: “For us, the picture cost $6 million and a year of our lives. For the audience it’s $3.50 and an evening out. If it’s a bum evening, it doesn’t make me any better or worse as a person. But if you think the film is you, if it is your effort to transform your lover into a producer worthy of a superstar [and] if you think it is a home movie about your love and your hope and your deepest feelings, if it’s your life that you laid out for the folks and they don’t smile back, that’s death.”

I’ve pasted it forthwith:

In the summer when school is out, Instamatics and flashcubes at the ready, they wait outside the homes of the stars. Hoping for a glimpse of Paul, or Clint, or Steve, or Barbra. A glimpse of a radiant life, full of wealth and fame and sex and happiness.

Pursuing in their lemming way this fantasy of stardom, they have driven Barbra Streisand and Jon Peters, her ex-hairdresser, now her partner in life’s adventure, as far as they can retreat, up a narrow country road, overhung with great oaks and eucalyptus, to a rustic ranch house buried in the Malibu mountains.

But the fans are already there, lurking outside the gate, glaring at visitors. Jon is not dismayed. He roars with exuberant laughter — “We’re training the dog to attack.”

Barbra is not happy. Her brow is furrowed and her eyes are full of hurt. “What do they want from me?” she asks. And yet they’re the paying customers whose unending eagerness to pay $3.50 and up to see Barbra show emotion is making all this possible.

All this is a golden forest, where Barbra and Jon are at play like children of the gods. The ranch house is all earth tones and artfully aged wood, peopled with Art Deco statuary, every corner filled with antiques, pictures, elegant rugs and throws and shawls, lamps, plants, objets d’art of every description, none of it going together, in such profusion only an impression of magnificence is generated. For some reason it doesn’t seem cluttered, which is perhaps part of Barbra’s secret. It is like a magical attic, in which every trunk and old discarded hat rack or moose head has a sentimental history, printed on a card. Nooks and crannies abound, a great house for hide and seek. It is completely satisfactory; I believe Barbra Streisand lives here.

A new garden is being started today, during my first visit. It arrives on a truck, and the entire thing is planted before lunch, with everything in bloom. It reminds me of an old Hollywood joke about Cecil B. De Mille and his extravagant film vision of the Bible: “This is what God would do, if he had the money.”

Warner Bros. has asked me to “do a fast rewrite” — is there ever a slow one? — of a rock musical version of A Star Is Born, and in a moment of mad ambition I accept on condition that I can direct it as well. If it’s okay with Barbra, its okay with them — the decision is hers.

The movie is the Mary Deare of the Hollywood seas. So far six writers and three directors have all abandoned ship, many in the middle of lunch. Joan Didion and John Dunne began it all two years before with the idea of a rock musical about a husband and wife, like James Taylor and Carly Simon, whose musical careers are parallel and competing. Though they’d never seen the originals — a sentimental romance starring Fredric March and Janet Gaynor made in 1936, then remade in the same manner, with music added, starring Judy Garland and James Mason in 1953 — the Dunnes called it A Star Is Born and brought it to Warner Bros who had made the Garland/Mason version.

It was instantly picked up by Warners as a vehicle for Streisand with whom they had an outstanding commitment. Soon Barbra was reworking the script, with Peters sitting in. At the end of their third draft and halfway through their second director, the Dunnes dropped out. Jon brought in new writers, and as directors fled the project, Barbra proposed Jon to replace them. Since Kris Kristofferson, who was to have co-starred, had also dematerialized along the way, Jon suggested himself to fill in.

A year later, when I arrived, they had accumulated 40 pounds of unusable scripts and a deadline (for legal reasons) to start shooting January 2, seven months away. Jon has apparently seen something his predecessors also saw. Now he’s quit a director.

I ask him why. Barbra looks at me sharply, as though seeing me for the first time. “It’s funny, you’re the first person who’s asked that.” she says. I sense she’s waiting to hear the answer, too.

Jon says. “How could I direct her and keep our relationship? I had to decide which was more important, our love or the movie.” That’s nice. He goes on: “You and Barbra make the picture. I’m here to expedite: You need somethin’, I’ll kick ass to get it.”

Have I read the scripts? they ask. “Yes,” I say. “They keep getting worse and worse.” “I don’t know what to do,” she says. “Do you?”

The trouble is, you can always tell where the trouble is: it’s what to do about it that’s tricky. As it stands now, there’s no part for Barbra. The Didion/Dunne third draft script is by far the best — sharp and tough-minded, authentic in feeling of the rock world. It lacks the sentimental love story that should be the movie’s heart. The man, a rock superstar, is dying inch by inch as his career collapses and he is consumed by the self-destructive demons that have pursued him throughout his life. His part is interesting all the way; the girl he meets (and marries) and helps to become a star is getting happier, richer and cuter: Her only problem is him. A hard part to create.

“What about Brando?” Barbra asks. “I always wanted to play with Brando. Why does it have to be a musical?”

Jon leaps up, excited now. “He was right here! He was cute! The son of a bitch, he wanted to f— Barbra—I was ready to kill him! I take him off, and I kiss him! He’s beautiful! Right here! I love him, the bastard! They’d make a great pair. Imagine. Streisand and Brando!”

This wasn’t the plan. She has to sing six numbers. That was what I had discussed with the studio. I asked why they had been ready to let Jon—whose total motion picture experience was a previous marriage to an actress, odd hairdressing jobs on movies, plus sitting in on the set during the making of Funny Lady — direct a $6 million musical, “It doesn’t matter,” a certain eminence grise said. “It would be nice if the picture was good, but the bottom line is to get her to the studio. Shoot her singing six numbers and we’ll make $60 million. We’d like it to be good, and that’s what we hope you’ll do, but if we have no choice …”

I try to get back to reality, but they’ve already overdosed. We tour the new garden. Barbra doesn’t like a gum tree Jon has located. “You’ve got to have it to balance the roof line. Listen to me, Barbra; goddamn it. I know design, that’s one thing I know.” Barbra doesn’t like it. The gardener is sent for – a gentle, aristocratic-looking European. He mildly backs Barbra: Flowers won’t grow under a blue gum tree. “Screw it!” Jon yells. “Do any goddamn thing you want!” He stalks into the gathering twilight. Barbra turns to me. “It’s my garden,” she says. “Why can’t I do what I want with it?”

In the morning, Big Red, the guard dog, is being taunted by the dog trainer, to make him tough. Big Red lies down, looking sullen but bored. The trainer finally gets a low growl. “He’s lazy. He just don’t give a damn, you can see it.” New dogs are ordered.

“What’s the story about?” Barbra asks me. I quote Oscar Wilde: “An actress is a little more than a woman; an actor a little less than a man.” She likes that.

It’s more than just a cruel wisecrack, I say. Since the original film, made in 1936, our feelings about almost everything—especially success and sex—have changed. It used to be accepted as a fact of American life, and a basic tenet of screenwriting, that heroines and heroes wanted success and money and fame as they wanted life itself. They believed they’d be happy once they got it, and they believed that though there were unscrupulous types cutting corners, it wasn’t necessary to be cruel or dishonest to achieve it. Nobody thinks that way anymore; the simple unvarnished dialogues of 1936 are embarrassing today. We need to update a sentimental romantic story for an audience that has become skeptical about sentiment and almost derisive of romance.

Fredric March in 1936 and James Mason in the 1953 version reached what seemed to be rock bottom somewhere about the eighth reel; they get busted for drunkenness. Their lives were going down the drain; the judges sternly lectured them. In 1976 everybody has done a night in the tank. Who cares?

But the real change is in the relationship of the sexes. In the old versions the men found it unbearable that their wives were successful and they were not. A delivery man brought a package for their wives and called them by their wives’ names. The humiliation was too great for a man in that time when men were men and women were tiresome necessities. And the issue of her success and his failure was seen in terms of a competition in which he lost, because she won. But today too many working wives and baby-feeding husbands don’t care.

The woman in our story is ambitious to become a star, but it is not necessary: it can make her happier and richer, but she could give it all away and not be a better or worse person. With stardom she is only a little more than a woman.

For the man, his career is his defense against a self-destructive part of himself that has led him into outrageous bursts of drunkenness, drugs, love affairs, fights and adventures that have made him a legend. His career is also what gives him his sense of who he is. Without it, he is lost and confused; his demons eat him alive. That’s why he is a little less than a man. And it is not that her success galls him, or that she wins over him; the tragedy is that all her love is not enough to keep alive a man who has lost what he measures his manhood with.

Jon says. “Does he have to commit suicide? That’s such a turnoff. Why can’t it be an accident?” I stare at him. It is the same question that pursued Selznick endlessly in making the 1936 version. I give him a copy of Selznick’s menu, detailing why suicide was essential then, and is now. Jon doesn’t read it.

“Well,” I say, “he doesn’t make some dumb theatrical gesture to make way for tomorrow, and he can’t walk into the water, not after Jaws. He dies of drink and dope and pushing his luck. Like Janis. She didn’t fire off a gun, but does anyone doubt she killed herself?”

“But I don’t like him: I hate him if he kills himself and leaves her all alone, this little girl.” Jon says.

They talk about themselves, and I realize they see their own story gloriously told in song and dance and color, a $6 million home movie.

“People are curious: they want to know about us. That’s what they come to see,” says Barbra. But then, she has second thoughts. “I don’t want you to use too much. I don’t know if I should tell you this or not, because someday they’ll want to do my life story, and I don’t want to use it up.” She tells how when the other kids used to listen to Elvis Presley she listened to Johnny Mathis, modeling her style after his. She sang in the halls other apartment building, because they rang like a concert hall, until the super threw her out.

Jon is eager to use details of their life together—how they make love, fight and love again—but Barbra is torn by second thoughts. “It’s not our life. You don’t want to make it too real.” The lines go in and come out again.

Every day trucks of furniture, antiques, trees, lumber and cement arrive. A guest house is finished and another begun. The house next door is bought and plans are begun to rebuild it in Jon’s style; another is bought to be rebuilt by Barbra in Art Deco style. A doubles tennis court is flung up, a swimming pool appears. The expenditure of energy is stupendous: the money obviously doesn’t matter. This is a restlessness that fills every moment with a new plan set in motion, a new idea that is instantaneously realized: “That’s me,” she laughs as I talk about it. “Instant gratification!”

“She’s got her house to work on, I got mine,” says Jon. “It cuts down on the fights.”

I had never seen a Streisand picture before. Now, secretly, I’ve been catching up, screening all of them – Barbra marching with her own clear force and direction regardless of what may have gone wrong or silly around her. She is a primitive force and an elegant delight:

I’m humble and amazed. What a fantastic picture we can make!

I begin work on the script, pasting bits and pieces of every draft starting from 1936 into the third draft by Joan Didion and John Dunne.

We begin talking about casting the lead.

It comes down to Jagger and Kristofferson, because we want to record the music live. As actors, neither has made pictures that tell much. But Kris seems more a romantic figure to me. To everyone’s amazement. Kris accepts the renewed offer to co-star without a struggle.

I am writing new scenes and dialogue and Barbra can’t understand why I must work alone. “It would go so fast if we worked together. I could tell you what to write.” I tell her I’m a bad collaborator. “So am I,” she says.

From this moment we never hear a word from the studio. We hire Polly Platt to begin production design. Everything that has been only a figment of someone’s imagination now begins take concrete shape.

Bob Surtees, 70 years old, a cameraman for 50 years, rich with Academy Awards and grumpily independent, rolls back from lunch and a couple of Scotches, happy he’s been paid on the Mike Nichols picture Bogart Slept Here, which was canceled because of stress between director and star. I like him, I introduce him to Peters, I start to list his credits—everything from Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo to The Sting. Jon gets impatient. “All right, all right. Whatever you want.”

Barbra reads the first script pages. We meet. She doesn’t mention anything about them. She picks up other drafts and reads scenes from each, one after the other. What does she mean? What does she want? Did she read what I wrote? I sneer at what she reads. Jon takes me aside for a heart-to-heart. I can’t understand what he’s talking about. I think they’ve picked the wrong person and suggest they get someone else.

They don’t seem to hear what I said. We go on anyway.

The problem is there is no place at the ranch to sit down and talk. We lie on the floor. Barbra talks about past directors. “I’m jealous of my director’s time. Willy Wyler really screwed up one musical number in Funny Girl; it was the one number he had to involve himself in. His ego got in the way: he couldn’t let it alone. I had an arrangement with Ray Stark—he let me go in after and re-edit the sequence: he promised he’d put it in the TV version, but he didn’t do it, he left it the way it was. It’s still wrong. The director got it backwards.”

“What about the others?” I ask.

“I get on with all my directors. They all realize I’ve got something to give.”

Her eyes, blue as summer sky, stormy as April, flashing ice. “I see pictures of myself talking to people. I’m just trying to say something, express myself, and in the picture I look like I’m desperate, full of anger …” she says. Eyes of a little girl maimed by silences.

The script takes shape. Cries of delight. And days of picking over dialogue word by word. I get bored.

“Listen, what about the style of the film? We never talked about it,” she says one day. I describe a fine line between the sentiment of the love story and the documentary reality of the background.

“What about the cameraman? Who is he? What has he done?” she asks.

“Bob Surtees? He won three Oscars, thirteen nominations.” I say.

“He’s old. We should have someone young on this picture. What does he know about backlight? Did he sign his contract’?” asks Barbra. Yes, I say. She lets it go.

Rupert Holmes, talented and elusive wraith from New York, is here to work on the music. Kris is in Europe making a picture. Rupert writes one song, very quickly and then bogs down. Holed up in his hotel, he avoids Barbra’s calls, trying to work out material. Barbra is getting frantic, and Jon talks to Rupert to get him moving. Rupert is frightened by Jon’s temper and grabs a plane for New York. We never hear from him again.

We interview musicians, music producers, song writers. I bulldoze Barbra into hiring Paul Williams and his collaborator, Kenny Ascher: they contract to do all the music.

They begin working with Barbra. Songs begin to emerge. Barbra reshapes them, attacking lyrics with a logician’s mind. She insists on precision and simplicity — on lyrics meaning exactly what they say and saying what they mean. It’s an education. Paul grows angry at the editing and the criticism. He stops answering his telephone. We beg for words on paper to study, but his notes are written in hieroglyphics on a collection of oddly-shaped pieces of paper, envelopes and cocktail napkins. He sings from them in Barbra’s townhouse, a glorious museum of antiques and fine art as cooks and maids and gardeners and helpers and repairmen wander through.

“With one more glance at you,” Paul sings … “I could learn to move the clouds/Until the sun shines through/Some new line here and then/ Refresh these weary eyes/With one more glance at you.”

There’s a squabble in the kitchen. Barbra’s cook told Jon not to look in the oven and he screams at her: “This is my house and don’t you ever tell me what to do in it!” He looks in the oven. The soufflé falls. The cook shrugs. We don’t know if dinner will be ready or not.

In the small hours of the morning, Paul is sent off to rework the lyrics. Barbra is a little panicky: we are running out of time. Paul won’t consult others for outside help. We begin to look ourselves. Paul grows angrier and angrier. “How can I write when I have to talk with her all the time and nothing ever gets finished because before I finish the damn song she’s already asking for changes?” he shouts.

Calling director Dianne Crittenden brings in actor/musician Gary Busey for a key role. Busey occasionally sits in on drums with Leon Russell. Through Busey, Barbra meets Leon. Leon’s wife has written a song Barbra wants me to hear. “I’ve found the most beautiful song,” she says. As she sings it to me, I watch her face. If I can capture that primitive simple joy she shines with now…

We’ve got two songs. It’s already late November. . . .

The script is done. We rummage back through it, comparing it to old versions, back to Dorothy Parker’s of 1936. I discover Barbra hasn’t read the descriptions or the stage directions of any of the scripts. In one scene that runs six pages without words she has never understood what happened. All that stuff bores her. She flutters through the script like a butterfly, touching here and there. Focusing a meeting, finishing anything is impossible. “I love rehearsals and readings,” she says. “You can try everything. I hate shooting: Everything gets so final.”

I determine not to finish the script – to keep everything spontaneous and fast, reveal little in advance to her and the other actors, freeze moments in time.

Jon is worried: “Frankee! Your turn — the Jewish princess wants you!” He gives advice: “She doesn’t think you like her, she’s getting panicky, and when she’s like that she starts calling in her friends.”

I go to lunch at her townhouse. The cook has made lobster soufflé, which Barbra knows I love. She sits against the window. “This backlight? Through my hair? You love it? I want a lot of backlight. I see myself this way. I know my face. I can feel the light when it’s right. This side is good. The other side, my mouth has this curve here — it’s no good. I’m better for comedy on this side, but for anything else, always on the left.”

“I know,” I say. “I noticed in your pictures you’re always on the right side, the man on the left. It gets monotonous.”

She agrees to be freer about allowing her bad side to show. The fact is that nobody else can tell the difference. It’s in her mind. But then her mind is as much a part of this picture as the budget and the schedule.

She is upset with me. “I don’t feel you really want to love me. All my directors have wanted to make me beautiful. But I feel you hold something back; there’s something you don’t tell me. You never talk to me.” I realize she’s serious. “I love you,” I say, “but I’m not the demonstrative type.” I talk about the need for distance, for tranquil and objective judgment of the film. She can knock directors and actors clean out of the practice of their profession with 10 percent of her energy. I have to guard against it.

We talk about directors and actors, how one always looks for a guide and a father figure to rely on. “But you fight like hell with Jon, you fight like hell with everyone you lean on.” I say. “I know,” she says. “Jon is so strong!” Then: “I never had a father: I was always in charge of myself. I came and went as I pleased. I can’t stand for someone to tell what to do. Ray Stark always used to bully me, the son of a bitch. I made him and he made millions from me, millions!

“You’ll pay,” she says, “for every lousy thing Ray Stark ever did to me.”

We’re six weeks from shooting and we have no music, only the beginnings of several songs. Barbra has lost her taste for Mary Russell’s song.

We hire Phil Ramone, a recording engineer and producer of strength, calm, integrity and taste, whom Barbra trusts from having worked with him before. He wants a fortune, but he is hired. Paul is furious. The production people are disturbed about the rate at which we’re spending money. Polly Platt is furious at me for resisting her script ideas and at Barbra for first overlooking and then overruling Polly’s production design. Barbra visits the sets, goes home, brings carloads of things —from what cellars and attics and closets God only knows — to decorate the fictitious Esther’s apartment as though it were hers.

Polly Platt and I have worked out locations and sets with an overall design that juxtaposes the insane tumult of the characters’ public life, the mobs and crowds and crazy emotions, with simplicity and calm for their private life together. The rock star builds a retreat in the desert, where for a hundred miles in every direction there are no people, no houses. They are alone together there. Barbra and Jon fight it bitterly: The open spaces seem bleak and unfriendly to them. They want to shoot it at their ranch. It is exactly opposite to the feeling I want. His suicide should happen in lonely desolation: They see Pacific Coast Highway, or maybe Big Sur. The arguments are long, exhausting and angry.

“What if I don’t like the location?” Barbra asks. “Then come take a look with me.” I say. But when Polly and I fly down to Tucson to finalize our plans, first Barbra, and then Jon, drop out. They don’t like to travel. “I’m like a big baby,” smiles Jon. “I like to be at home.”

They go to New York. A blessed relief. Without the endless questioning and explaining, we are able to set schedules and locations. Sets are designed: casting is locked in.

From New York we hear that Jon has been in a fight; he knocked out a man who heckled Barbra at a TV telecast of a Muhammad Ali fight in Madison Square Garden. When they come back he grins happily: “Pow! I let him have it! He made a motion like he’s gonna touch, maybe he’s gonna hit Barbra: He’s gonna hit my woman! I go crazy! Bam! Pow! They’re pullin’ me off him. The cops come take him away. You can’t go anywhere with her! That’s the meaning of ‘star’! We gotta get that in the picture!”

Kristofferson has made changes in Paul’s music to adapt to his style and his band. Paul doesn’t like it: Barbra and Jon don’t like the sound of Kris’s band — they don’t sound enough like Bruce Springsteen, who has just been on the cover of Time. I don’t like the basic songs involved. I feel it isn’t too important as long as a hard rock sound evolves. It hasn’t: we’re all unhappy.

We meet. An empty rehearsal stage at Warners: ranks of empty folding chairs, musicians’ instruments still up, lonely guard by the door and the phone. Under a pool of light at center stage the fight rages: Kris leaps to his feet, cords standing out in his neck: “Who shall I say says my music isn’t rock — Barbra Streisand’s hairdresser?” Jon screams back at him: “It’s shit. I don’t care who says it!” Williams and Ascher sit silent. Barbra and I, like a duet, shout at Jon to lay off.

It’s apparent that Kris has been lying about the music. He hates it, and he’s frightened of feeling like a fool. He dreams of the moment Dylan sees the movie, of what Dylan will think of him: in marijuana dreams he reads Rolling Stone’s review. This is his soul and his career, and if he’s not feeling right with the music, he’ll quit. Barbra and I seem to be the only ones who recognize the moment when it comes. We must decide: Go with Kris’s changes or find someone else. There is no choice.

Barbra muses: “You work to become a star, and you think you have all the power, and then …” I finish the sentence for her: “Some idiot actor won’t say the line.” She misses the irony, but understands the thought. I take Kris to dinner. We get drunk, he tells me about his life; It’s the old story—a short-haired, clean-thinking patriotic helicopter pilot split open by drugs, booze, sex and music to release a free spirit. He certainly sounds happier now than he was before.

I hear later that Paul Williams is outraged by what he views as a betrayal by Barbra and me; he blames it on Jon, who actually fought the hardest for Paul’s point of view. Jon, pushed too far by this knife in the back, yells at him: “Where the hell were you? You didn’t say a goddamn word.” Williams knocks over chairs. He looks up at Jon and takes a punch at him. The guard starts to call for reinforcements. Paul walks out. He owes us pages of lyrics. They arrive by messenger. He won’t come to the phone.

In his living room, which is a recording studio, Leon Russell plays a song for us. Barbra is enchanted. Leon sits at the piano, heavy-lidded, watching her without expression. Barbra excitedly learns the song, complains about a key change, revises a lyric, tries it again, revises more lyrics. Russell watches, listens. Barbra runs out of suggestions. “Will you make the changes, then?” she asks. Leon: “I like it the way I wrote it. If you like it, take it. If you don’t, I’ll write another.” Barbra can’t believe it.

They work together, but nothing comes, until one night Leon comes back from the john to find her noodling a classical-sounding tune on the piano while she waits. It’s a tune she wrote. He thinks it would make a pretty song. She protests: it goes too high. He makes her play again and improvises lyrics on the spot. Barbra is running a tape recorder. She plays it for Jon and me; it’s a scene for the picture. But Barbra is shy, afraid to use her music. Jon and I plead, argue, reassure, insist. I write it into the script.

It turns out to be a highlight-sweet, moving, a little sad. Kristofferson, croaking like a man living on too much whiskey and not enough self-assurance, is superb.

Jason, Barbra’s son by Elliott Gould, and Christopher, Jon’s son, ages nine and seven, invade a story conference. They want to know if they can go out in front of the house and watch the fans.

Tomorrow we begin to shoot. Script revisions have eaten up my time; rehearsals have been sacrificed to prepare the music. I badly underestimated the time needed to prepare a musical film. We need another three months. All the continuity sketches and shot diagrams I have laid out seem impractical, impossible. The schedule allows no flexibility, no going back for retakes. We’ve already postponed a month; we can delay no longer. Barbra has a rash, but her weight is down. Suddenly her driving angry force fades; she is almost resigned. Tomorrow the options to change stop; everything will be frozen on film.

We shoot a musical number—Barbra singing on a tiny stage, minimal choreography, a crowd, Kristofferson barging in, making a disturbance that ends in a fight. We are recording the musical numbers live, a “new” technique that, in the beginning, actually was the only way musicals could be made. Everyone is feeling his way, experimenting, doing things for the first time. Barbra sings to make you forget tension, worry, uncertainly; she soars above it all. You feel excited and wonderful. She throws it away as though it were a gift not worth having.

And the first day’s shooting is gorgeous: People cry and laugh in the dailies, Barbra embraces me and Bob Surtees. Tears in her eyes, she says, “Thank you! Thank you! Thank God.” Surtees has made her look better than she has ever looked. We all feel a deep relief: The movie is going to be a hit.

A movie set, as Orson Welles was the first to say, is the most wonderful electric train a boy was ever given to play with. What he failed to add was that most of the time it doesn’t work. You tinker, wheedle, stick in bent pins, tape it up with Band-Aids and spit, and it runs in fits and starts when it damn well pleases. Actors can’t, won’t, never will be able to say crucial lines; lights fail, time runs out, cameras break, tempers flare. I approach it with detachment, watching carefully the direction in which the flow of errors and accidents, improvisations and corrections is taking us. Barbra resents it terribly: It is a limitation of power, beyond the reach of her desperate need for control.

There is a moment for writers when their characters seem to assume a life of their own, beyond the will of the writer: we have reached the equivalent moment for a director, when the actors become one with their roles. It is a moment, in Bertolucci’s words, to “throw away the script and set sail on a sea of improvisation.” I would not go so far, being a writer myself, and because this script is unusually carefully crafted. And because Barbra in many ways is more loyal to the script and the words than I. She feels I am too permissive, “too nice” to actors. “You have to be hard on them,” she says. “They’ll walk all over you!”

I am staging a moment when Kris marches onstage: screaming extras rush through security guards to get close to the stage, deluge him with flowers. Barbra arrives late and, seeing the extras poised, ready to attack the stage, fails to understand they will move. She screams at me: “Why are they here? They should be over there!” I start to speak. She shrieks in a baby’s desperate wail: “I want it!” It has the power of primitive will, full of loneliness. I ignore it.

The days and nights wear on. Discussion and rehearsals are impossible. Barbra can never settle on a final reading or version, and nothing gets done. Our exhaustion begins to deepen.

We set up a scene in Bernie Cornfeld’s house. Jon begins to make suggestions. I ask him to be silent or leave. He begins to yell. Barbra and I are both yelling at him to get out. He leaves. We rehearse and shoot. Later, in the dark, I seek him out, telling him rehearsals are an exploration. You can’t cut in with suggestions and criticisms until afterward because it stops the unfolding of the actors’ impulses: They become self-critical before they have even felt through their lines. I don’t know if he understands. He says only. “It’s all right, it’s not you I’m pissed off with. It’s her.” I realize that all he’s aware of is a personal affront.

Later, as I walk to my car. Barbra darts out of the hedges, running stooped low behind cars in the dark. “For God’s sake, take me home!” she says. She shivers, huddled in a corner of the dark car. “He gets so furious. I don’t know what to do.” I can see she is physically frightened. I offer to take her home to sleep at our house. But Jon is not home when we arrive at her place. Small and tired and scared, she walks into the gigantic house, all the lights shining.

When she was first starting in New York, she once told me, she slept anywhere: she lived alone, and she was never afraid. Now she is terrified to ever be alone — especially in the big house, where under each antique and precious thing, the Laliques and Klimts and Tiffanys, she says she has pasted a tag so in case it all evaporates some day she’ll know how much she paid for everything. The house is silent.

Barbra resents Kristofferson’s direct approach to acting. To play drunk, he gets drunk. Of his role in the movie he repeats again and again:

“Somebody’s been reading my mail.” Her lightening-fast pace confuses him. “Jesus. Barbra, wait a minute! Where do you want me to go?” Barbra grows progressively more watchful and judgmental of his performance — less able to concentrate on her own. But her own attention is fuzzy. She can’t set into the emotional state needed for a high scene. Kris cries readily; she needs menthol blown in her eyes to make them tear.

Kris apologizes. “Jesus, Barbra. I’m sorry. I wish I could do something to help you. It’s my fault. I’m not giving you what you need.” Barbra takes me aside “Did you hear what he said—the ego? He thinks what he does controls what I do!”

We struggle with the scene. Barbra’s anger at him begins to work for her. The scene is raw and harsh, as it should be. But the struggle dulls our perceptions. We feel unfulfilled and unhappy.

I go to Kris, full of anxiety, remembering the naked rage he showed at Jon over the music. “The booze, Kris. I got to talk to you about it …”

“What? Is it making me sloppy?”

I regard him with amazement. He thanks me profusely for calling it to his attention. Tell him anytime, but it won’t happen again.

We shoot a bath scene. Barbra comes to me: “For God’s sake, find out if he’s going to wear something. If Jon finds out he’s in there with nothing on, naked …” I double check and discover that Kris has taken his characteristically direct approach. I get flesh-colored shorts for Kris. He is derisive: “What the hell are I they afraid of?” During the shooting, Jon’s go-fer girl stands by watchfully to report. Jon stays away.

‘You think it’s easy?” he asks me later, “Some dude making love to your woman?” When we rehearse love scenes, we keep the dressing room doors open.

In dailies, Barbra’s mood swoops and plunges with every nuance of light on her cheekbone or unexpected camera move. “There! My God, look at her she’s beautiful!” we shout. Or a bit of staging she doesn’t like plunges her into a despair and rage that is vomited back in a savage attack: “This is shit! God what are we going to do! I told you not to do that, why did you do it? It’s wrong!” Everything is seen in terms of right or wrong: there is no personal preference, nuance or shading. The crew and staff drop out of screenings as the critical battles escalate, and even Surtees no longer comes.

Soon we are alone in the dark. In the end, I stop going, for I know what we’ve shot. If there’s a doubt or a problem, I get up early and watch it with the editor on the KEM machine. In the morning it is quiet and I can think.

Polly Platt stays away on location. Nobody wants to get caught in the middle. The flow of ideas and interchange of feelings and reactions that enriched our first days dry up.

It is three weeks before the outdoor rock concert, for which we’ve rented a vast football stadium in Phoenix. The scene will run at most five to eight minutes on screen. The action involves Kris showing off to Barbra by taking her onstage at a huge concert. Drunk and coked up, he abandons the music and, trying to ride a motorcycle onstage, loses control and zooms off into the audience. It is the last straw and will ruin his career. We must fill the stadium, which takes some 40,000 or 50,000 people. It is essential to get some feeling on screen of the weight and size and pressure in the lives of rock musicians. Jon has been full of mad schemes. Now, only three weeks away from shooting, the planned all-day live concert turns out to be nonexistent. This is a disaster of such magnitude that I cannot think about it. All I can do is shoot whatever is there the day we arrive.

The action I have planned is detailed in sketches. Barbra and Jon want to see them. “This is the heart of the picture, this is the action part for people like me!” Jon says, bouncing around the office. He acts out his idea of how to do it. He wants to hire Evel Knievel for $25,000, construct a jumping ramp so Knievel, doubling for Kris, will drive the bike off the stage through the paying customers for a hundred yards, scattering them like bowling pins, and, hitting the ramp, fly into the air from the audience 150 feet back over the stage and crash into the instruments. The stunt of the century. Something nobody who sees this picture will ever forget. “For people like me, who like action. We got to set some action, some excitement into this picture.” He is pacing about feverishly. I look at Barbra. She’s not listening. “Listen, where are the close-ups?” she asks. “There are never any close-ups in this picture. When I worked with Willy Wyler, we had close-ups in every scene.”

I call her attention to some of the more recent close-ups, forgetting my decision not to discuss these things with her. Soon we are embroiled in exactly how close up a close-up really has to be to be called a close-up. Jon studies the storyboard for the stunt. “This is shit,” he says.

We have no concert, I remind him. Let’s get the concert organized before we worry over the stunt. Promoter Bill Graham is hired to get together a concert. After a month of Jon’s waffling about, Graham has it all nailed down in a few days, together with a schedule that allots me four hours on stage with camera, in two two-hour sessions. Peter Frampton is the topliner. We are selling tickets at $3.50 apiece. We might even make money. “I’m paying him a fortune.” Jon crows, “but he’s worth it. He’s tough, he’s like me, he’s a street fighter.”

Evel Knievel has been forgotten.

We look at a first assembly of major scenes, the recreation of the Leon Russell piano incident. Kris croaks the lyrics to her music with a boyish delight. He sounds as if the music and the words had only that moment occurred to him. He is perfect. She is magical. Words are no good for it; the scene simply makes you feel wonderful. Barbra is crying. “It’s better than my dreams!” she says. And then she turns to Peter Zinner, the editor. “But Peter! You used the wrong take! Why did you do that? That was a mistake!” We patiently explain the difficulties of cutting, how sometimes you have to sacrifice a marginally better take in order to get a better rhythm, or to be able to use some other piece that is essentially better. She is unconvinced.

“When I get the film,” she says to me later, “will he do it my way?”

I check. Barbra’s companies own the negative. She has final cut on the film. Barbra is preoccupied with a press party Warners is giving, flying in reporters and photographers from all over the country for a conference, a luncheon press party on the set and the outdoor rock concert the next day.

Kris, uptight about press, worried over his music, is tense, angry over her interference. His new record has just come out and been panned by Rolling Stone and most everyone else. He’s drinking tequila washed down with cold beer.

Barbra rehearses with the band on her numbers and uses up Kris’s time, so he has no rehearsal. Coldly furious, he refuses to come out of his trailer. “Goddamnit!” he says. “I’ve got to go out and play it in front of 60.000 people, but she doesn’t give a damn.”

Barbra and I are trying to explain a minor change; we agree for once, but Kris has had all he can handle. He doesn’t want to be told what to do with his music. He explodes. Barbra explodes. The mikes are open: they are screaming at each other over a sound system that draws complaints from five miles away. The press is delighted. This is what they came for. Sulks in trailers. Jon Peters threatening Kris. Kris talking tougher. The director knocking on trailer doors, playing Kissinger. Notable quotes. Quotable notables. You read about it in Time.

Now our differences have become news events. It heightens the tension, and the feeling of being perpetually misunderstood. These clashes happen on all pictures: they become part of the creative process from which the picture emerges. They are unavoidable. And the press is uncontrollable and mischievous. They know a good story when they see one, but we wish they’d check their facts.

At seven o’clock in the morning, the dawn brushes the crowd with blood orange. They are there. By mid-morning some 55,000 curiously clean and docile people are listening to the opening acts. It is overwhelming. The sheer size and sound of the crowd reduce our conflicts and tensions to a proper perspective. But the communications are incredibly difficult. I have a schedule of shots in mind: I run from setup to setup. At the morning break, the two-hour session during which we have the stage, I face horror: The props and set dressing for our action have all been pushed back and replaced with instruments and amps and paraphernalia of the various acts onstage. The first hour of our allotted two is wasted moving furniture to match what I’ve already shot.

The crowd is mercurial. Fifty-five thousand strong, they scream and chant: “No more filming, no more filming!” though we haven’t even begun. We make the shot. Things break, a plug-in wire for Kris’s guitar is too short, nothing works. Nobody can hear. The noise, the pandemonium, the incipient panic are all but overwhelming. I remember the advice of a London bobby about facing crowds and one’s own tendency to panic: Imagine a piano wire attached to the inside of one’s skull, stretched tight all the way through the body and down to the center of the earth. Nothing can move you. Zen.

We are off. Graham is screaming: “How can you be so disorganized? They almost started throwing things!” I can’t slop to argue about who screwed up the set dressing. I have to run for the helicopter to film the air-to-air and air-to-ground shots. Barbra and Jon are lunching with her psychotherapist, a Ph.D. who sends Barbra dialogue suggestions from time to time. The crowd isn’t the disheveled mess of OD’s and outre nymphets and druggies we anticipated. They’re hostile, but only to the filming. The minute Barbra sings “People.” every bourgeois cell in their bodies responds with a standing ovation. Her magic works anywhere.

Exhausted, pounded by the noise that is so loud it is felt in the gut like a blow from a giant soft fist, we stagger through the afternoon. Barbra can’t understand the moving shots I’ve laid out onstage; it is simply too hard to explain. Graham regards us with outrage, and he is yelling too: “Don’t you know what you’re doing? They’re going to kill us!” He points to the jeering mob. But Barbra won’t go to her mark until she’s yelled herself out.

In this maelstrom of sound and anger and rushing time, I file away in my mind each foot of film, an angle on her, his turning to her there, that will fit in with her look to him, and then cut back to his move across camera is okay, her on left of screen; then back again before the cut, to get back into continuity. Each piece shot and filed away, adding up to the two miles and add-a-bit of film that will make up the final movie. Sulking, she takes her mark. I shoot.

Dailies are wonderful, but not wonderful enough. Barbra and Jon can’t see how they go together. They are convinced it’s disaster. “You’ve ruined it! How could you do that? We can never do it again!” But the key shots are there. No one will ever be able to understand why the number one camera on the boom failed to drop down to reveal the crowd at the moment we planned. Everyone is angry, exhausted. After this night no one from the camera crew ever comes to dailies again. To me, it is a miracle we got through the day at all. We have a helicopter shot revealing the crowd that is like a kick in the solar plexus — Kris dissolving before the crowd: it’s there. It’ll have to wait until we can put it together before they will begin to see.

I have never been so tired, not since World War II. I begin to realize that Barbra and Jon are frightened, and their fears are focused on me. “If this film goes down the drain,” she says. “it’s all over for Jon and me. We’ll never work again.” I point out the obvious. “All you have to do is offer to sing and they’ll fall all over you to do a picture. Why are you trying to panic yourself this way?”

“I know,” she says, “but what will happen to Jon?”

Barbra has a rash and a cold. Kris is seldom outside his dressing room.

We are running late, and the film is terribly long. I make a cut in the script, dropping two pages of needless introductions to a scene, regaining half a day on schedule, and giving us time to set up and rehearse a musical number. Barbra is coldly furious. “You lay it out and it’s shit,” she says. I tell everyone to go someplace and relax for awhile and take Barbra to a back room and lock us in. “You’re rude,” I say. “There’s no reason to talk that way to me, so don’t do it anymore. You’re in a rage. What’s that about?”

“Because I should have co-director credit.” she says. “I’ve directed at least half of this movie. I think I should have the credit for it, don’t you?” I laugh.

She is already executive producer, which worried her when she assumed the title: Jon is billed below her as producer. She has indeed exercised final authority on the major matters of style, storyline, etc., that producers traditionally did in past times and some still do. But so much is beyond any human control, so much has had to be accepted, even though she disagreed. Now she is feeling desperate. She feels she has done it all, in spite of everyone, against terrible odds, but, she says, she isn’t greedy. “You’ve contributed a lot.” she adds.

I tell her I’ll share the director credit with her. I tell her the same thing I once told Bob Rafelson, who wanted to do a picture with me, but explained, up front, that as director he made tremendous contributions to screenplays of pictures he directed and would have to have cowriting credit.

“Well. I make tremendous contributions to the direction of any picture I write.” I had told him. “so it’s a deal. I’ll split your director’s credit with you, too.”

Barbra stares at me. “You mean costarring Barbra Streisand and Frank Pierson?” “I’m not so sure about the order of billing,” I say.

I ask her why, if she didn’t want someone to lake the load off her, she didn’t direct it herself. “I couldn’t just take over as director from Jon, could I? I wanted someone to be a buffer between Jon and me.” I tell her I’m not interested in being a buffer between her and Jon. She persists: “What about the credit? I don’t think I can insist on it. People criticize me enough as it is: they’re always waiting to attack. I think it’s something you have to give of our own free will.” I smile at her. “I’ll think it over,” I say.

I unlock the door and bring her back to the set. The subject of credit is not mentioned in my presence again. Everyone pretends nothing has happened. For a day there are nothing but professional working problems. I am almost happy.

Illness is sweeping through the exhausted crew. They have no strength left to protect them from this virus that brings laryngitis, two or three days of nausea and high fever, and leaves them shaking with weakness. We all have it. I realize my peak illness was during the outdoor concert. Thank God I didn’t get the fever.

Kris faces a difficult scene. In it he forgets the lyrics to his signature song, breaks down on stage and then brings Barbra on to sing in his place. The dialogue makes him denounce his own music as “tired old shit.” Kris doesn’t like it: it seems to touch some chord of fear in him that relates to more than just our script. We have also been shooting for days with Barbra and neglecting him. He is drinking tequila and beer, and improvising a song about me. I hear it: It is insulting. I pull him into the nearest available room and tell him I can take any amount of anger, but this spiteful meanness is like writing messages on men’s room walls. His flood of wrath and frustration pours out. He doesn’t like the scene. It’s untrue and inappropriate. He took this movie because he thought we were going to make some true statement about the rock music world. Instead we’re making a Barbra Streisand lollipop extravaganza.

It’s my fault. I won’t stand up to her. Nobody stands up to her. Everybody just folds up. I yell back, “Including assholes who crawl into a bottle.” The fact is that on this scene I agree with Barbra: we never differed. We yell some more. It feels good. Finally, the flood of anger is reduced to the point where we can discuss the scene. It is not that the character believes his music is bad. He is only tired of it, singing the same old song over and over. He knows his own energy has gone out of it, and her energy is new and fresh, and that’s what he wants the audience to hear. Kris seems to accept it. Anyway, he agrees to go on. We apologize to each other.

Suddenly we are aware of several frightened faces peering out at us from an inner door. We realize we’ve been in the women’s restroom, trapping ladies on the pot. “Come out, it’s safe. it’s all over now,” I tell them.

We have advertised locally that the theater we’re working in is open to visitors to hear Barbra sing. We almost fill the theater. They stay all day, a brutally long movie working day. Some have flown, hitchhiked, driven from Oregon, Maine, Canada. They are thrilled to have been a part of it. They have worked for free. They beg Barbra to sing just one song especially for them. She won’t.

She quotes a line I put in the script, a loose adaptation of something Dylan once supposedly said: “Just because they love my music doesn’t mean I owe them anything.” But the line has been dropped from the script.

There is only one more concert sequence, which will open the movie. Jon has given up on promoting any more concerts. The auditorium in Tucson holds 11,000 people. We will have to work with extras. At first I am promised 500 per day. I work out sketches and plans of shots, using photographs of the place from angles that conceal as many seats as possible, while giving the illusion of showing the entire space. I believe we can work it with 2,000 extras. That is some $40,000 worth of extras for one day. To my amazement, it is agreed. Some 1,500 show up.

We are halfway through. We are on schedule and a little under budget. The picture looks magnificent. I am sick, exhausted. Barbra looks at me. “You’re bored.” she says. She’s right.

We are shooting night scenes in the parking lot of a motel in Phoenix, Arizona. The Academy Awards are on TV. Bob Surtees is nominated for The Hindenburg. Bob is sick and crotchety. I duck into the bar in time to watch myself win the screenwriting award for Dog Day Afternoon. The bar erupts in applause. I am astounded at how good I feel. I suddenly realize I’ve made a bad mistake. I should have flown back to Hollywood, rented a dinner jacket, played the game. In this little world of movies the Oscar changes your life, inside and out, whether you choose to respect it or pretend a cynical disregard. Brando pretends to be above it all, treating the business with the same disdain he treats himself, but he recognized its power enough to use it to promote the Indian cause. I glow: I feel untouchable. I sense a subtle change in people s attitude toward me.

The messages, telegrams, bottles of champagne and brandy arrive endlessly. About midnight. Barbra calls. “How do you feel?” she asks. She sounds careful, as though she doesn’t know what to say, or how to say something she’d like to say. Fantastic. I feel. Untouchable. We can’t think of anything else to say. “How did the shooting no tonight?’ she asks.

I pack, and assistant director Stu Fleming and I pile into a rented car with some of my cold champagne. We celebrate by driving to Tucson to get an early morning start. Bob Surtees is too sick to work. We replace him for a few days with gentle and capable Ernie Laszlo, who skillfully matches Bob’s incredible work.

Barbra and I fight over a scene involving Kris and her wrestling on the ground. She wants mud, an awful lot of mud. I don’t want so much mud. There is another scene, involving her failure at baking bread, for which she dresses in red plush, dabs flour funnily on the dress and cutely on her nose, and talks a kind of funny double talk through her nose. I tell her it’s out of an old I Love Lucy show, but for this scene she has the unreasoning love of Titania for Bottom.

I shoot it under protest, knowing time is growing short and it will never appear in the film’. Now the wrestling is done, and it is bad. I insist on reshooting in a more life-like tempo and tone. She is coldly angry, which is not like her.

Jon, who has been in L.A., flies in that night. He appears in my room at midnight and raves until two, sent by Barbra. To do what? “You don’t listen.” He says. “You’ve never listened to us. You just go ahead and do it your way. You’ve never doubted, never asked a question.”

I don’t see what he is getting at. He begins abuse. I get a drink and go to the bathroom, the door open. I can hear him shouting in the living room. He goes over the long list of what they see as my failures: the motorcycle stunt, which I begin to argue about. This is not a movie for stunts —the business has to look real and unforced. I remember I’m not dealing with reality and go back to urinating. He talks on and on. I realize that he is here to try to force me to quit. Or did she tell him to fire me? Whatever it is, it seems to have worn him out. Without ever getting to the point of what he came for. Jon suddenly blurts out: “I’m not afraid of your Oscar.” And leaves.

In the morning I discover she has replaced, without discussion, two professional actors in bit parts with her personal manager and the president of First Artists, a company that is part owner of the film, and in which she is a principal stockholder. I am appalled. It is too early to call my agents, and I’ve already set up the camera. I turn the whole mess over to Barbra and leave. She begins to rehearse the bewildered group, soon throwing out the script and improvising. It is embarrassing. I can’t reach my agent.

The hours pass. The strain begins to tell. Jon is suddenly standing before me, yelling. I tell him to keep his voice down, because I can’t hear him. I suggest he fire me. Suddenly he is confused. “I’m sick of you.” he yells. “I’m waiting until the production is finished. Then I’m going to punch you out.” It is a nightmare that has no end.

The production manager pleads with me to do something. Barbra is stymied, confused. The actors are in positions that are impossible to shoot. I restage them, change a lens. We shoot. Slowly we rebuild momentum. Barbra is quiet. No one talks about that morning ever again. When my agent calls me back that night I tell him it’s all okay, not to worry.

Later, Barbra and I talk about Jon’s temper. “When we were in New York,” she says, “Jon got mad at something I said. He put his fist right through a closet door. I’m so afraid he’s going to hurt himself.” I decide not to ask about the Ali fight incident. Instead I mention our argument. “I begged him to fire me,” I said. “Why didn’t he?” she asks. “He doesn’t have the guts,” I say. “You’re wrong,” she says.

It is after midnight on Lankershim Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley. Kris and Barbra play a scene about marriage. I call. “Cut. print!” We are finished. It seems impossible. Kris drifts away after a perfunctory handshake. Barbra and I hug. I thank Bob Surtees and his incredible camera crew. It was my aim to avoid self-conscious moves, to make the camera invisible and, unfortunately, no one will ever know the technical wonders they have achieved to make that possible. The rest of the crew packs up—sullen, exhausted, without a sound.

We are on schedule, a little under budget. Tomorrow I can sleep.

Instead of a “wrap” party, the customary bash thrown for the crew and cast on the set at the end of shooting, Barbra and Jon throw a gigantic party, taking over the entire Mandarin restaurant in Beverly Hills. It turns out to be Barbra’s birthday. Everyone appears with presents for her, and she plunges into the huge pile like a delighted child. We show excerpts from the musical numbers, and cheers shake the place.

In the back of the restaurant, away from the excited people crowding around Barbra, her son, Jason, knocks things off tables, tears a tablecloth off, spilling glasses and ashtrays onto the floor. Barbra is told, and sends her secretary to deal with it.

In the morning I receive a note telling me that my cut of the picture is due in less than four weeks. Lawyers exchange terse letters to establish my legal right to cut the film for six weeks from the time of first assembly. Barbra wants to work with me on my cut, in exchange for which I will be allowed to consult to the end. I refuse.

Peter Zinner and I feverishly work to get a version of the picture done in six weeks. We manage a rough but serviceable cut, and show it to Barbra, Jon, a few special guests.

As the picture plays, something tightly wound inside me, something that has grown tighter and heavier for a year, suddenly unwinds in my gut: a warm rush of relief and pleasure dispels the dread and doubt. It is going to be all right. The music is wonderful. She is better than my dreams, and he seems at last to have fulfilled his promise: He is warm, sad, sexy, a man who seems to have lost everything but the painful memory of how to love. It’s rough and unfinished, and as in all films there are scenes that seem amateurishly awkward and crude, but they are swept clean out of mind by the power of the rest.

Barbra kisses me, and thanks me. It feels, somehow, like a goodbye kiss. In the morning I find that the scheduled screening for Warner Bros. has been canceled. And when I arrive at the studio to pick up the TV tape copy of my cut of the film which had been promised, I discover the copy has been sent to Barbra. Apparently she wants no one to see my version. There are furious phone calls all day and all weekend. At last the studio is able to get Barbra to agree to let them have their only view so far of what will be their biggest release of the year.

The Warners people are unanimous after they see it: It is a huge hit.

She moves the editing to the Malibu ranch. She hires extra teams of editors. A phalanx of female advisors pores over the film with her, and slowly she falls further and further behind schedule, lost on a sea of infinite possibilities—staving off moment by moment the time when final decisions must be made, when the film at last will have to go public.

Once we talk, when I have heard she is showing the film to John Dunne and Joan Didion, who so long ago set this thing in motion—oh, mad unknowing engineers of my fate, be careful! I want to see it with them. Barbra is distant, but I manage to strike a few familiar sparks, as we have at it: “Goddamnit. I’m saving your ass, don’t you understand?” she says. “Nobody asked you to save my ass, you took it on yourself. I want to save my own ass,” I say. And anyway, I’ll know better than she what condition my ass is in, when I see the picture.

It is September. Jon calls. “I want to bury all the crap. I want us to be able to go out together behind this picture. We want you to see it with us tomorrow.”

The lights go up.

It’s the same picture; nothing much has been done to it, except polishing and smoothing and trimming, the usual business, some of it competent, some brilliant. But something has gotten lost.

We talk lamely: although I am complimentary about the technical finish, my reaction is clearly bad. We say perfunctory goodbyes. What went wrong?

All night the movie plays over in my head. Kris’s character often seems an unpleasant drunken dangerous bore: she seems silly—why would she love him? I see she has speeded up the film by cutting his establishing scene, moments of boyishness, of feeling the pain of his existence, that make us feel for him and with him; she has cut his reactions—when something happens to him, she cuts away from his reaction, so we fail to know how he feels. The sadness, the wonderful wasted quality Kris brought the part, the exhaustion and the playfulness with which he courts her, his delight in finding her is diminished or gone, in order for the film to dwell on her.

I write a long letter detailing what and where the film has been cut that causes this strange and pervasive loss. She doesn’t call back.

I hear she is stunned and shocked by my letter. I hear she is furious. I hear that what she has taken out of the movie is being put back in.

Years ago, or so it seems, I drove up that sun-dappled lane to the ranch: we had a dream of a picture then, each of us with a slightly different view. Out of the differing dreams, the struggle and conflict of personalities, accidents and quirks of fate, moments of rage, disappointment, cowardice, arguments, mistakes and sometimes sparks of brilliance struck off each other in the heat of battle, a picture has emerged that is not her dream, nor mine. It is something else we don’t fully recognize, like a photograph a little out of register so that each image blurs the sharpness of the others below. Soon the first audience will see it, and they will know.

For us, the picture cost $6 million and a year of our lives. For the audience it’s $3.50 and an evening out. If it’s a bum evening, it doesn’t make me any better or worse as a person.

But if you think the film is you, if it is your effort to transform your lover into a producer worthy of a superstar. If you think it is a home movie about your love and your hope and your deepest feelings, if it’s your life that you laid out for the folks and they don’t smile back, that’s death.

An executive voice is reassuring on the phone. “You made great movie – it’s all there. Maybe you’re right about a cut here, a cut there; it still doesn’t matter, it’s a hit.”

Has he seen it?

“No. But that’s what I hear.”