I don’t have instant comprehensive recall of each and chapter of Seymour Hersh‘s reporting career, but I know a lot about it.

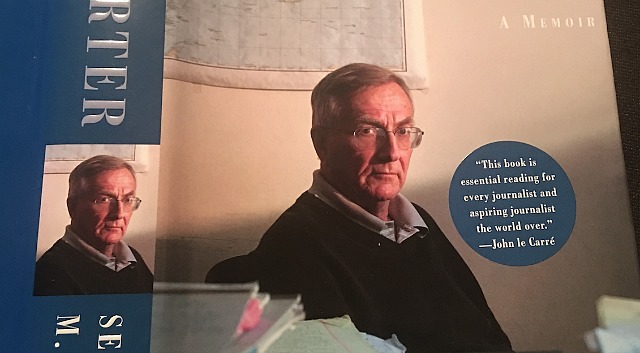

Seven years ago I read a few chapters from Hersh’s “Reporter“, and it was almost entirely riveting.

So I wasn’t exactly blown away by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus‘s Cover-Up, as I knew many of the stories and details and whatnot. It was nonetheless immensely soothing to watch.

Anyone with the slightest interest in Hersh’s work or who understands that the calibre of journalism that Hersh delivered in the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s and ’90s is pretty much absent today, please see it for affirmation’s sake. Even those who know nothing of Hersh’s work, seeing Cover-Up is pretty close to essential. The thought is that others might try to follow Hersh’s example, and that it can only do good to spread the gospel.

From Hersh’s “Looking for Calley“, published in a 2018 issue of Harpers

Hersh: By early 1969, most of the members of Charlie Company had completed their tours and returned home. I was then a thirty-two-year-old freelance reporter in Washington, D.C. Determined to understand how young men — boys, really — could have done this, I spent weeks pursuing them. In many cases, they talked openly and, for the most part, honestly with me, describing what they did at My Lai and how they planned to live with the memory of it.

In testimony before an Army inquiry, some of the soldiers acknowledged being at the ditch but claimed that they had disobeyed Calley, who was ordering them to kill. They said that one of the main shooters, along with Calley himself, had been Private First Class Paul Meadlo. The truth remains elusive, but one G.I. described to me a moment that most of his fellow-soldiers, I later learned, remembered vividly. At Calley’s order, Meadlo and others had fired round after round into the ditch and tossed in a few grenades.

“Nightmare From half A Century Ago“, an HE post that appeared on 6.17.18:

It’s hard to set aside time to read a book when you’re already putting in several hours a day on a column plus the usual chores, reveries and occasional screenings. Last night I nonetheless read five or six chapters of Seymour Hersh‘s “Reporter“, which hit stores less than two weeks ago.

I read the ones about Hersh serving as an Associated Press Pentagon reporter and as press secretary for the presidential campaign of Eugene McCarthy in late ’67 and ’68, and two chapters about his breaking the My Lai massacre story — “Finding Calley” and “A National Disgrace.”

Of course and indisputably, “Reporter” is a page-turner. First-rate writing and reporting — pruned to the bone, no wasted words. I was completely hooked and immersed, and then appalled all over again when I got to the Calley chapter. After I finished I found “Finding Calley” in a recent Harper’s post.

Remember that scene in Full Metal Jacket in which a blustery helicopter gunner regales Private Joker (Matthew Modine) and Rafterman (Kevyn Major Howard) with stories about how he “sometimes” mows down women and children, etc.? That was, of course, the My Lai sensibility, albeit diluted for mass consumption.

Seymour Hersh, “Looking for Calley” (Harpers):

“One GI who shot himself in the foot to get the hell out of My Lai told me of the special savagery some of his colleagues — or was it himself? — had shown toward young children. One GI used his bayonet repeatedly on a little boy, at one point tossing the child, perhaps still alive, in the air and spearing him as if he were a paper-mache pinata. I had a two-year-old son at home, and there were times, after talking to my wife and then my child on the telephone, when I would suddenly burst into tears, sobbing uncontrollably. For them? For the victims of American slaughter? For me, because of what I was learning?”

“Hersh’s initial My Lai report broke on 11.12.69. He wrote about the atrocity in ‘My Lai 4: A Report on the Massacre and Its Aftermath‘ (’70), but a long excerpt in Harper’s appeared a few weeks before that. Hersh had interviewed nearly 50 Charlie Company perpetrators. The initial indictment said that 109 My Lai (or Son My) villagers had been murdered — the figure was actually 504.

“Two years later a second Hersh book, ‘Cover-up: The Army’s Secret Investigation of the Massacre at My Lai 4‘, was published.

“I visited the My Lai Massacre Museum, which is built right upon the actual village where it all happened, five and a half years ago — on 11.22.13. It felt exactly as bad as I expected it would be, but I had to do it. I had been to Dachau a year and a half earlier.

“Scene of the Crime,” a Seymour Hersh article about My Lai — The New Yorker, 3.23.15:

Then came a high-pitched whining, which grew louder as a two- or three-year-old boy, covered with mud and blood, crawled his way among the bodies and scrambled toward the rice paddy. His mother had likely protected him with her body. Calley saw what was happening and, according to the witnesses, ran after the child, dragged him back to the ditch, threw him in, and shot him.

The morning after the massacre, Meadlo stepped on a land mine while on a routine patrol, and his right foot was blown off. While waiting to be evacuated to a field hospital by helicopter, he condemned Calley. “God will punish you for what you made me do,” a G.I. recalled Meadlo saying.

“Get him on the helicopter!” Calley shouted.

Meadlo went on cursing at Calley until the helicopter arrived.