Maximilian Schell, the much-honored actor-director with the cultivated European air, died last night in Innsbruck at age 83. My dominant memory will always be his electrifying performance as Hans Rolfe, the clever German attorney who defended Burt Lancaster‘s Ernst Janning in Judgment at Nuremberg (’61), for which he won a Best Actor Oscar. Schell/Rolfe was a blend of crackling intelligence, necessary poise, a burning determination to be heard and a nativist resentment of American occupiers. He didn’t just hold up his end in that Stanley Kramer film — he was a virtuoso, a young actor riding a perfect storm of talent, timing and a first-rate script.

Schell’s other noteworthy performances: the larcenous, tuxedo-wearing mastermind thief in Jules Dassin‘s Topkapi (’65), a hyper and obsessive German officer in The Young Lions (’58), a Holocaust survivor with a hidden idetntity in The Man in The Glass Booth (’75), an anti-Nazi activist in Fred Zinneman‘s Julia (for which he was Oscar nominated and was given the New York Film Critics Circle award for Best Supporting Actor) in 1977, and Tea Leoni‘s estranged father in Deep Impact (’98).

Starting in the late ’60s Schell began to direct, write and costar in several German-produced films of his own devising, almost none of which I saw or even paid attention to. But the Oscar-nominated Marlene (’84), his documentary about Marlene Dietrich, was a major standout. Schell was forced to creatively adapt to a tough situation when Dietrich changed her mind about appearing in present-tense interview footage. But he managed it well and won a NYFCC award for Best Documentary.

The Austrian-born Schell was quite the handsome continental smoothie during the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. But at some point during the ’90s his eyes changed, his voice became deeper and more guttural, and he grew a beard. In one of the oddest transformations in motion picture history (particularly for a good-looking guy who began as a German-styled Montgomery Clift by way of Cary Grant), Schell more or less became a variation of Akim Tamiroff. This, at least, is how he seemed to me in Little Odessa (’94) and particularly in Deep Impact. That 1998 disaster fick was mostly ludicrous, but the “oh, Daddy” scene on the beach between Schell and Leoni was moderately affecting.

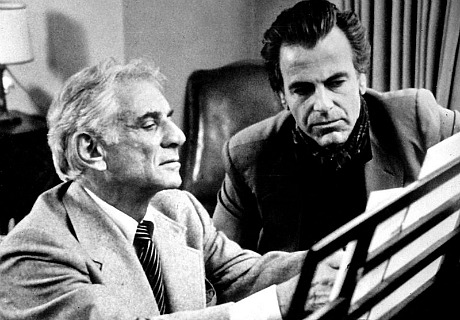

The highly cultivated Schell was a respected pianist (recognized as such by no less an authority than Leonard Bernstein) and classical music devotee. In 1983 he and Bernstein co-hosted an 11-part TV series about Ludwig van Beethoven that featured included live symphonies plus discussions of Beethoven’s works. Schell also worked with Italian conductor Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, which included a Chicago performance of Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex, and another in Jerusalem, of Arnold Schoenberg‘s A Survivor From Warsaw. Schell also produced and directed live operas.

Schell and Leonard Bernstein in 1983.