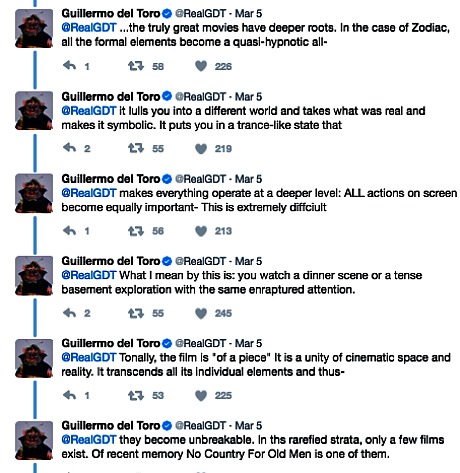

I wasn’t interested in Cinefamily’s recent ten-year-anniversary screenings of Zodiac for one reason — they weren’t showing the 162-minute director’s cut (five minutes longer than the theatrical version, highlighted by the black-screen musical time passage sequence). But Guillermo del Toro‘s recent tweet-stream about David Fincher’s 2007 classic got me going again.

Last night I dusted off my director’s cut Bluray and and sank into it deep. Once again I was in hardcore Fincher heaven. This film is gonna live forever — I knew that the first time I saw it. Eternal shame upon (a) those clueless Paramount execs who insisted on cutting Zodiac down to 157 minutes, and (b) the Oscar blogaroos who didn’t rally round because Paramount had released it on 3.2.07, which of course meant it wasn’t Best Picture material.

Oh, and by the way? Fuck The Game — the end of that fucking film drives me up the wall.

All hail the performances and the reality brought to bear by Jake Gyllenhaal, Mark Ruffalo (best thing he’s ever done), Robert Downey Jr. (ditto), Anthony Edwards (career peak), Brian Cox, Elias Koteas, Donal Logue, John Carroll Lynch and Dermot Mulroney.

From “Zodiac and Fincher,” posted on 12.1.07:

“The Zodiac ‘director’s cut’ (out on DVD on 1.8.08) screened the night before last at the Variety screening series at the Arclight. I drove over right after the Sweeney Todd screening and caught the last 45 minutes. I’d seen this cut on a screener a month ago, and yet I felt curiously riveted, glued. I was going ‘wow’ all over again. This is what great movies do — they refresh their game and deepen and spread out a bit more every time.

“The percentage of Oscar handicappers and Academy apparatchiks who truly get this — who understand that Zodiac is the ultimate Shelby Mustang of ’07, a film so unique and special and unified that even half of the supposed cine-sophisticates don’t quite get the full splendor of it — amounts to a slender slice of the pie. But what a feeling it is to know. I’ve never been so certain of the right-on rootedness of any film in my life. The people who scratch it off their Best Picture lists shall think themselves accurs’d they were not here, and hold their manhoods cheap forevermore.

“Zodiac director David Fincher, producer Brad Fischer and screenwriter James Vanderbilt sat for a q & a with Variety critic Todd McCarthy after the screening. Fischer had a good quote that I didn’t write down — ‘This is a newspaper film, not a serial killer film…more in the realm of All The President’s Men‘ — but no one felt inclined to say what it really is.

“Maybe it hasn’t struck a deep enough chord because most viewers haven’t been down the road that Jake Gyllenhaal‘s cartoonist character goes down. The quiet madness of an all-consuming obsession. Or maybe a lot of people have and it makes them uncomfortable.”

From “Building Suspense Along the Trail of an Invisible Man,” a N.Y. Times essay by Manohla Dargis, posted on 1.6.08:

“One unsettling scene involves four men just talking in a room. Two are San Francisco detectives, Dave Toschi (Mark Ruffalo) and William Armstrong (Anthony Edwards), and the third is a sergeant, Jack Mulanax (Elias Koteas), from another city where the killer has struck. They have arranged to meet a suspect, Arthur Leigh Allen (John Carroll Lynch), at his workplace, an oil refinery some 30 miles southwest of San Francisco.

“The scene takes place almost precisely halfway into the movie and opens with a sweeping pan across an industrial vista crowded with belching smokestacks and oil tanks. It then cuts to the detectives filing through a hall in the refinery and past a mounted wall sign that warns, ‘Be Careful Safety First.’

“The detectives, dressed in muted shades, settle into the room, which has both brick and painted walls. The bricks are taupe, and the painted walls are the pale, institutional green familiar to any American who attended public school in the 1960s and 1970s. A smattering of bright, almost luminescent yellow chairs and a vividly red Coca-Cola machine daub the room with color like beacons.

“The movie cuts to an adjacent hall in which two other men are walking, one with a lumbering gait that seems to keep time with the low rhythmic pounding first heard (and almost unnoticed) when the detectives entered. This is Allen, who, after calmly settling into a chair, will make a chilling case for his character’s guilt.

“The three detectives sit in a semicircle — with Armstrong behind a table — facing Allen. Initially the scene unfolds straightforwardly with a series of over-the-shoulder shots and countershots. (In these shots, as the name implies, the camera seems to peer over the shoulder of a character whose body is only partially visible.)

“This shot-countershot pattern is interrupted only when Allen crosses his legs, a gesture followed by a cut to Mulanax looking at one of Allen’s feet, which now looms in the lower center of the frame. (The killer wears similar boots.) The over-the-shoulder shot-countershot sequence resumes until Allen volunteers that he was carrying bloody knives in his car the same weekend as one of the assaults.

“Allen’s startling admission leads to a shot of Mulanax looking straight into the camera in close-up. This shot is soon followed by similarly framed head-and-shoulder close-ups, first of Armstrong and then of Toschi, each staring directly into the camera. With these near-identical, shared looks, the three finally seem to see — perceptually, intellectually — the stranger before them, the story’s invisible man. In this moment sight becomes knowledge, however tenuously grasped.

“Not long after, referencing one of Zodiac’s ciphers, Toschi tells Allen, ‘Man is the most dangerous animal of all.’ Allen responds, ‘That’s the whole point of the story.’ It is also the point of this scene, which in under six minutes lays out the movie in miniature.”