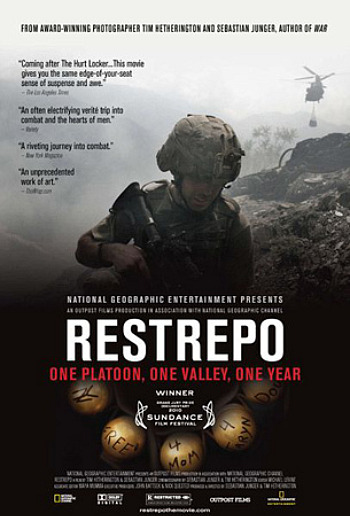

I think I’m done with war documentaries that make a point of not offering any sort of opinion about anything — no history or context, no political point of view, just “this is war, war is hell, taste it.” Well, I’m sick of that shit after seeing Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger‘s Restrepo, a bravely captured, technically first-rate documentary about a year under fire in Afghanistan’s Korangal Valley, a.k.a., “the valley of death.”

There’s no question whatsover that this movie lies through omission about what’s really going on in Afghanistan in the broader, bigger-picture sense. I found myself becoming more and more angry about this after catching Restrepo two nights ago at the Walter Reade theatre, and especially after doing some homework.

Hetherington and Junger spent a little more than a year (May 2007 to July 2008) with several U.S. soldiers in that besieged neck of the woods. They focused mainly on the grunts’ hilltop camp called Restrepo (pronounced res-TREP-o and named for a medic in their unit who’d been killed). The film does a clean and competent job of portraying their endless firefights with Taliban forces and their community dealings with the locals, and it acquaints us with various members of the hilltop platoon — their faces, lives, impressions — in what seems like a frank and forthright manner.

Except the kind of frankness that Restrepo is offering is, to put it mildly, selective. For realism’s sake Restrepo chooses to isolate its audience inside the insular operational mentality of the grunts — “get it done,” “fill up more sandbags,” “ours not to reason why” and so on. In so doing it misleads and distorts in a way that any fair-minded person would and should find infuriating. Is there any other way to describe a decision to keep viewers ignorant about any broader considerations — anything factual or looming in a political/tactical/situational sense — that might impact the fate of the subjects, or their mission?

Imagine a documentary about the day-to-day life of Steve Schmidt, John McCain‘s ’08 presidential campaign manager, that ignores how the campaign is going and instead focuses on Schmidt’s relationship with his family and his dentist and his kids’ homework and his visits to a local cafe and his dealings with the guy who mows the lawn once a week. What would you call that approach? Thorough? Honest?

Rest assured that if I was one of those Korangal troops I would ask a shit-load of questions about the general game plan, as in what the fuck are we doing there and how the hell do we ever get out? But nobody wants to go there, least of all Hetherington and Junger, and so Restrepo is just about cigarettes and weapons and wrestling matches and firefights and sandbags and a cow that got stuck in some barbed wire and had to be killed, and then had to be paid for in order to chill down the locals.

I’m of the view that the Afghanistan War is pure quicksand, and that we can’t help to prevail (i.e., defeat the Taliban or at least reduce them to insignificance) because we’re foreign invaders and sooner or later all invaders are out-lasted by the natives, and that natural organisms will infect and weaken them, and as a result they’ll eventually pack up and go home. Ask H.G. Wells or Ho Chi Minh.

We’re not stopping another 9/11 from happening by fighting there. We’re just fighting a series of skirmishes and offensives that will continue for years to come, perhaps even decades, and which can’t hope to lead to “victory.” It would be great if the Taliban could be finally defeated, sure, but it’s not going to happen and any military or intelligence person who claims otherwise is dreaming. The bottom line is that (a) we can’t win and (b) there’s no way out other than just quitting.

Quitting is un-American, you say? Shameful, unthinkable, cowardly? Well, two months ago U.S. forces up and quit the whole Korangal Valley offensive. That’s right — they shined it. The lives of 42 Americans who died fighting there over the last four years? Water under the bridge, U.S commanders decided. Better to cut bait than waste more lives.

(l.) Sebastian Junger, (r.) Tim Hetherington during filming.

In fact the general thinking (as expressed in this 4.16 N.Y. Times story) is that U.S. troops’ presence in the valley may have actually made matters worse by creating Taliban sympathies among once-neutral Korangalis.” Or so it says in the Times story as well as this Wikipedia summary.

This massive fact has been ignored by Restrepo — they could have easily added a tagline in the closing credits — and was not mentioned by Hetherington during the post-screening q & a.

I asked Hetherington if he could offer his civilian-observer, non-military perspective about whether he could foresee any circumstance that might allow U.S. commanders to decide, as they’ve done in the case of the Korangal Valley, that U.S. efforts to defeat the Taliban simply aren’t working and that it’s time to just pack it in. Hetherington got my drift, but he ignored it and blathered on about how the Afghanistan situation is different from Vietnam in the ’60s.

Hetherington has been a war photographer for years, and guys like him are basically action junkies — let’s face it. He seems almost invested in the Afghanistan conflict, perversely, because it provided him with a year’s worth of adrenaline rushes as well as the opportunity to create a noteworthy film and contribute great pics to Vanity Fair. In any case he’s apparently determined to follow the script set out by The Hurt Locker — i.e., our film isn’t preaching, not taking a stand, just showing how it is for the troops, etc.

(l.) Hetherington, Rachel Reid during Friday night’s q & a at Walter Reade theatre.

“What I’m asking,” I repeated, “is if there’s any way out of this conflict, or are we going to be there…you know, five or ten more years or indefinitely or what?” Rachel Reid, an Afghanistan researcher for Human Rights Watch who was sitting next to Hetherington, said that U.S. allies were getting a little fidgety and that the U.S. economy was impacting the situation and other generic blah-blah stuff.

Restrepo doesn’t tell you what’s going on and Hetherington and Reid weren’t in the mood, so consider the following:

A 12.22.09 CNN story by Peter Bergen reported that “a December 22 briefing, prepared by the top U.S. intelligence official in Afghanistan and obtained by CNN, concludes that the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan is increasingly effective.

“The briefing, which warns that the ‘situation is serious,’ was prepared by Maj. Gen. Michael Flynn last month. His assessment is that the Taliban’s ‘organizational capabilities and operational reach are qualitatively and geographically expanding” and the group is capable of much greater frequency of attacks and varied locations of attacks.

“According to the unclassified briefing, the insurgency can now sustain itself indefinitely because of three factors: (a) The increased availability of bomb-making technology and material; (b) The Taliban’s access to two major funding streams, one from the opium trade and the other from overseas donations from Muslim countries, which reach the Taliban by courier or through a system of informal banks known as ‘hawalas’ that operate across much of the Islamic world; and (c) the Taliban’s continuing ability to recruit foot soldiers based on the perception that they ‘retain the religious high-ground,’ and factors such as poverty and tribal friction.

This morning N.Y. Times columnist Frank Rich reminded that Gen. Stanley McChrystal “is calling the much-heralded test case for administration counterinsurgency policy — the de-Talibanization and stabilization of the Marja district — ‘a bleeding ulcer.’ And that, relatively speaking, is the good news from this war.”

That quote came from a 5.24.10 McClatchy story by Dion Nissenbaum that read as follows:

“U.S. Army Gen. Stanley McChrystal, the top allied military commander in Afghanistan, sat gazing at maps of Marjah as a Marine battalion commander asked him for more time to oust Taliban fighters from a longtime stronghold in southern Afghanistan’s Helmand province.

“‘You’ve got to be patient,’ Lt. Col. Brian Christmas told McChrystal. ‘We’ve only been here 90 days.’

“‘How many days do you think we have before we run out of support by the international community?’ McChrystal replied.

A charged silence settled in the stuffy, crowded chapel tent at the Marine base in the Marjah district.

“‘I can’t tell you, sir,’ the tall, towheaded, Fort Bragg, N.C., native finally answered.

“‘I’m telling you,’ McChrystal said. ‘We don’t have as many days as we’d like.'”