Lili Anolik‘s Vanity Fair piece about Pauline Kael’s misbegotten attempt to become a Hollywood producer and then a Paramount development executive, which happened between 1979 and ’80, is a hugely enjoyable read — wonderfully sage and lusciously phrased. It’s certainly one of the best inside-Hollywood articles I’ve consumed in ages — the story of a creative Hollywood demimonde that was destined to run aground — and a reminder of why I used to really love reading VF.

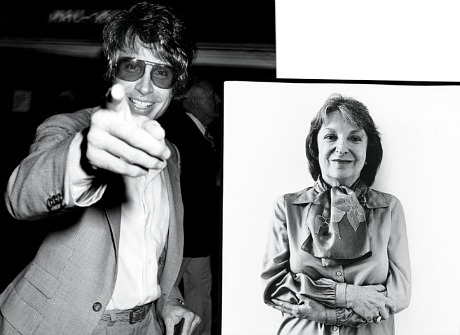

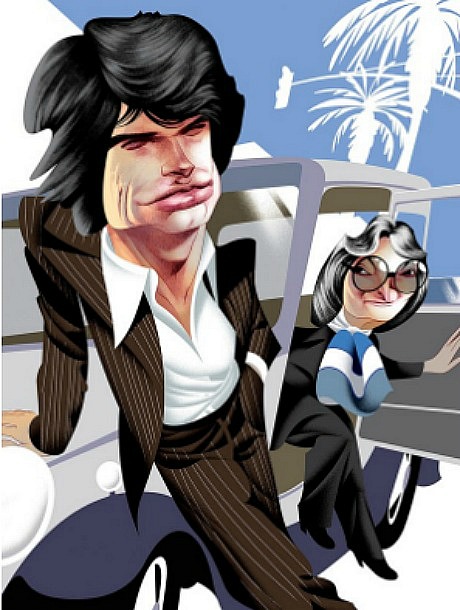

“In 1979, New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael, 59, accepted an offer from actor-director Warren Beatty, 41, to help him produce Love & Money, a script his production company had acquired and set up at Paramount,” the story begins. “Love & Money was to be the second feature of writer-director James Toback, 34, whose first feature, Fingers, Kael had reviewed ecstatically the year before. Toback was also a personal friend. She took a leave of absence from The New Yorker, headed to L.A.

“Kael and Toback began working together. She wanted substantial changes to the script. He did not want to change the script substantially. She was removed from the project. Beatty secured a new deal for her at Paramount as a creative production executive.

“At the time, Paramount’s chairman was Barry Diller, a fan. It was not to Diller, however, that she would be reporting. It was to Don Simpson, senior vp of worldwide production. There were a number of properties she wished to develop. Simpson rejected all but one. Her contract was for five months. When it lapsed, it wasn’t renewed. She returned to The New Yorker in the spring of 1980.”

That’s the basic set-up but consider the following passages, which are so beautifully concise and on-target they’re making me want to read it again.

Excerpt #1: “And didn’t that spate of Hollywood movies from 1967 to 1979, from Bonnie and Clyde to, say, Apocalypse Now, feel like a crime spree? As if the American New Wavers were pulling a fast one? The spree couldn’t last, of course. Sooner or later lawmen, i.e., studio men, would catch up. Or, worse, audiences wouldn’t. Times had changed.

“Kael understood this. In 1978’s ‘Fear of Movies,’ she wrote: ‘Now that the war has ended…[people have] lost the hope that things are going to be better…so they go to the movies to be lulled.’ But I’m not quite sure Beatty, who was considerably younger and had been knocked around far less, did.

“The chaos of the ’60s and early-to-mid-70s — Vietnam, Watergate — made for an opening, though it was closing quick. Kael prophesied the end of Pauline and Warren when she wrote of the ‘new cultural Puritanism,’ as surely as Bonnie prophesied the end of Bonnie and Clyde when she wrote of the ‘sub-gun’s rat-a-tat-tat.’ Did Kael foresee, too, the medium’s end? That the VHS revolution was just around the corner? That the 70s would be the last decade in which movies were truly a tribal experience?”

Excerpt #2: “By getting behind Toback, an artist, yes, but also a pickup artist, the protege of composer Aaron Copland and orgy buddy of football player Jim Brown, Beatty and Kael would prove that the spark hadn’t gone out of their rebel spirits, that they were still subversive, undaunted, young. Viewed from that angle, the crazy scheme starts to seem not so crazy after all, or possibly just crazy enough to work. Of course it was neither. It was the look Bonnie and Clyde exchanged — passionate, agonized, doomed — before the hail of bullets.”

Excerpt #3: “Kael’s mistake, I think, was in believing she needed the movies. Really, it was the other way around. Movies are an art that is only intermittently an art. She, however, was an artist, always and invariably, the equal to any director or actor she covered, the superior to most. In writing about one thing, she managed to write about all things. Her movie reviews were cultural criticism, sociological treatise, personal essay. Through sheer passion and craft, she transformed what was intended to be a consumer guide into a literary vehicle as supple and expressive as the short story or sonnet.

“Not by the end, though. The form she started out transcending she wound up trapped by. And the final scenes of her career were the final scenes of Sunset Boulevard, except she was Joe Gillis and Norma Desmond, the writer floating dead in the swimming pool and the actress-murderess descending the staircase as the cameras flashed, a star who’d outgrown the pictures that had gotten so small.”