I was lucky with the ladies for a fairly long stretch, from the mid ’70s until the late 20-teens. My hound-dog period ended precisely in June of ’17, when Tatiana and I tied the knot.

Before that moment I was mostly just fortunate. Either women find you attractive or they don’t. You can’t talk them into anything they don’t want to do — they hold the cards and control all the traffic lights.

I was a celibate, low-self-esteem nerd in my teens, but after hitting my early 20s I was blessed with dozens of glorious green lights for many subsequent decades. (I was faithfully married between ’87 and ’91.)

In this respect Alfred Hitchcock was one of the unlucky ones. He was obviously quite brilliant, wealthy and powerful during his directing heyday (mid 1920s to mid 1960s), but women found him ugly and Uriah Heepish, and despite his obvious interest and heated libido he never got anywhere.

When he entered his early 20s he should have just said “aahh, fuck it…God has both gifted and cursed me, and I’m just not going to score…women find me grotesque and that’s that.”

Alas, Hitch kept expressing himself in sexual ways throughout most of his life. Indirectly (mostly through surrogates) but creatively and forcefully.

For many decades the standard narrative about Hitchcock has been that he was more than a bit of a misogynist — cruel, pervy, sexually frustrated.

This view was launched almost exactly 40 years ago by Donald Spoto‘s “The Dark Side of Genius” (’83). It certainly got the ball rolling.

Roughly 29 years later Spoto served as script consultant for Julian Jarrold‘s The Girl (2012), an HBO/BBC flick based on Spoto’s Hitchcock books (the other two were “The Art of Alfred Hitchcock” and “Spellbound by Beauty”). Hitch and his Birds/Marnie victim Tippi Hedren were played by Toby Jones and Sienna Miller. (Not a good film.)

In the fall of 2016 came “Tippi: A Memoir”, in which Hedren passed along first-hand accounts of Hitchcock sexually assaulting and generally pressuring and tormenting her…”I’m giving you a career…how about some reciprocity?”

On 6.21.18 noted critic David Thomson posted a London Review of Books essay about Hitchcock‘s notoriously perverse (and arguably misogynist) Vertigo. The piece questioned whether Vertigo was an acceptable fit in the #MeToo era. Given Hitchcock’s creepy attitudes toward women on-screen (and his behavior toward Hedren in the early ’60s), Thomson doubted that Vertigo would be #1 again when Sight & Sound critics voted in 2022.

Thomson turned out to be right. In an act of seeming woke ballot-stuffing, Chantal Akerman‘s Jeanne Dielman became the new S&S champion.

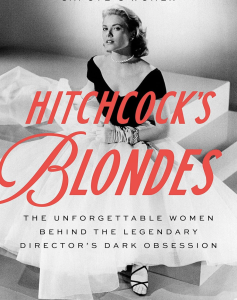

Now comes another Hitchcock study, one that basically says that he greatly enhanced the careers of several blonde actresses even though he was a fascinating creep — Laurence Leamer‘s “Hitchcock’s Blondes.”

Yesterday The Atlantic posted a mostly negative review by Matthew Specktor, titled “The Baffling Cruelty of Alfred Hitchcock.” Here are excerpts:

“Despite a title that may come off as objectifying, Leamer’s book is in many ways empathic and thoughtful, and he seems ready to train a generous eye on these actresses, to extract them from Hitchcock’s shadow without shoving the director under the wheels of his own limousine.

“The Hitchcock depicted in these pages is lonely and remote, yet also controlling and often vicious, at once fearful of and fixated upon sex, a devoted caregiver to his wife during her later years and, as Leamer is not the first to speculate, possibly undiagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome.

“The intention here is not so much to redraw our understanding of Hitchcock as it is to shift the emphasis altogether: to provide a new picture, or rather a series of pictures, of the actresses whose lives and careers are too often viewed in relation to the director’s.

“The problem is, Leamer doesn’t quite bring enough to the table. He doesn’t have much in the way of new information, and however nobly he strives to foreground the women in Hitchcock’s orbit, the book comes to life only when the director emerges from the wings to reclaim the stage. Leamer’s attention to the details of the actresses’ erotic lives can also give off a whiff of misogyny.

“In between, the reader is treated to a competent but not wildly enlightening history of how Hitchcock shifted his focus from one leading actress to another, from Bergman (who in Leamer’s telling sets the template for future leads with her blend of coolness and open sexuality) to Kelly (with whom the director rebounded after Bergman decamped to Italy to work with Roberto Rossellini) to Novak (who escaped from her unhappy contractual arrangement at Columbia Pictures to give her brilliant, career-defining performance in Vertigo) and so on.

“This approach starts out solidly enough, but as Leamer follows each figure through the contours of her upbringing, early career, work with Hitchcock (dutifully recapping the plot of each film along the way), and subsequent events, before returning to the director’s next film and next star, one’s attention begins to flag.

“After the French actress Brigitte Auber rejected Hitchcock when he forced a kiss on her, a few years after she’d appeared in 1955’s To Catch a Thief, she remarked, “It is difficult when someone is so ugly, like him. That turned-out lower lip. When someone is ugly, it isn’t their fault. The poor cabbage had a wonderful soul, I know.”

“I like to imagine that wonderful not in a charitable sense (it’s difficult to imagine Hitchcock as an exemplary soul) but in the ambiguous one in which James himself frequently deployed the term to mean, also, its opposite.

“That very doubleness is the thing, after all, that gives Hitchcock’s best work its charge, that gives Vertigo the wallop of tragedy while flooding it, too, with the most delicious current of irony. It isn’t that his people aren’t just criminals or voyeurs or monsters but rather that they are entirely so that makes them so pitiable.

“For Hitchcock to feel himself, the unattractive child of emotionally withholding parents, to be a monster, and for him to strive for a measure of revenge against the kind of exquisite beauties who might have spurned him in real life is one thing.

“But his ability to turn, say, James Stewart, the all-American star of It’s a Wonderful Life and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, into the emotionally disfigured Quasimodo of Vertigo and the Ahab-like obsessive of Rear Window — to take this monstrousness and invite the audience to identify with it — is in part what gives his films their psychological depth.

“One wishes ‘Hitchcock’s Blondes’ had a trace more venom in it, or some of the arch wit with which the director approached his own subjects. As it stands, Leamer’s attempts to paint the actresses in Hitchcock’s films in all their complexity (Kelly’s exuberant sensuality, Novak’s class insecurities, what he terms Hedren’s “narcissism”) have the opposite effect, flattening the women out until each one seems weirdly diminished. Though Hitchcock’s Blondes is an interesting-enough guide to accompany his films, I still can’t help but think the time reading it might be better spent rewatching Psycho or Strangers on a Train.